Khilkhet eviction: What is illegal and what is just?

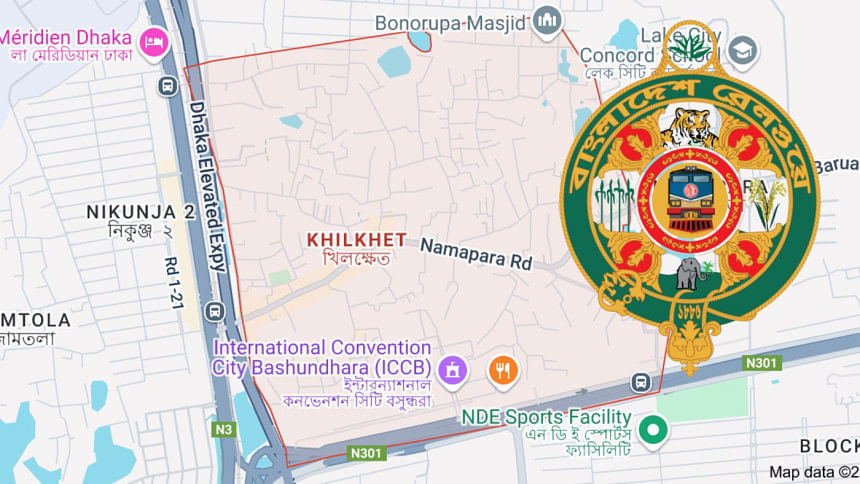

The images that recently emerged from Khilkhet, Dhaka have been stark and unsettling: broken concrete walls, twisted tin roofs, and uprooted bamboo poles lying scattered under the newly built elevated expressway. In a matter of hours, what had become a familiar sight for locals—a cluster of shops, a string of semi-permanent offices of political parties, and a small, makeshift Durga Puja mandap—was reduced to debris by excavators dispatched under a drive to clear "illegal establishments" from Bangladesh Railway's land.

At the site, about half a kilometre from Khilkhet rail gate to the playground before the entrance of Purbachal 300-Foot Road, the railway authorities carried out their eviction campaign claiming that none of these structures were authorised. That claim, in a strictly legal sense, appears accurate. Whatever their purpose—commerce, politics, or worship—these establishments did not have a legal right to occupy public land. In the eyes of the state, the law does not distinguish between a shop, a party office, or a religious establishment if none possesses valid approvals. And in principle, this is not an unreasonable position. The law must be neutral and uniformly enforced. If the government selectively tolerates certain illegal encroachments because of their political or religious affiliations, it sets a dangerous precedent where everyone claims exceptional status and public land is gradually usurped by private interests.

Yet, the principle of legality alone does not account for the complexities and sensitivities of our society. In Bangladesh, communal tensions have sometimes led to violence. When the demolition of a temporary place of worship occurs, the optics of the state's action become more fraught than any argument about legal title can fully resolve. And when religious symbols are demolished, no matter how temporary or unauthorised, the emotional trauma inflicted on the community may outweigh the material damage.

The authorities argue that the eviction drive was routine, that they acted equally against all illegal structures, and that even verbal notifications were issued before enforcement. The problem lies not in the assertion that illegal is illegal, but in how that principle is applied in practice and communicated to the public. The same law that empowers the government to reclaim public land also obliges it to protect religious harmony. If eviction is implemented in a way that could even be made to appear to validate communalism, even inadvertently, it risks sowing deeper divisions. And if the authorities are unable to distinguish between a business that sells tea and a pavilion used for worship, then they fail in their obligation to balance enforcement with social cohesion.

One cannot ignore that this incident did not occur in a vacuum. Bangladesh has, in recent years, witnessed some communal tensions. Reports of attacks on the homes of some communities have left deep scars in the national consciousness. Against that backdrop, the demolition of a religious structure—temporary or not—assumes a gravity that a purely legalistic reasoning cannot dilute. That gravity was evident in the reaction of the Bangladesh Puja Udjapan Parishad and the Bangladesh Hindu Buddhist Christian Unity Council, both of which expressed outrage and demanded accountability. The Bangladeshi Ministry of Foreign Affairs reiterated the country's commitment to equality and inclusion and urged observers not to react without verifying the facts.

For many ordinary Bangladeshis who are neither religious leaders nor legal experts, the question remains: could this eviction have been conducted differently? The answer is almost certainly yes. Even if the railway authorities believed the pavilion was an unauthorised structure, they could have issued a public notice and engaged with the temple committee in writing, so there was no confusion about the expectations or deadlines. They could have provided for the safe relocation of the temple materials, instead of inviting outrage on social media.

That is not to say that law should be suspended for religious structures. It is to say that when people's faith is involved, the same legal process must be carried out with more transparency, more patience, and more tact. Whether it be a madrasa, a church, or a political party office, the same logic applies to any encroachment. How the law is enforced determines whether it earns public trust or fear. This is not only a matter of sensitivity but also of strategic governance.

The Khilkhet incident also highlights the plight of the poor Bangladeshis. For many small vendors whose shops were demolished, this eviction is a question of survival. While the authorities insist on verbal notification being enough, common sense suggests that when people's livelihoods are at stake, a written notice, a timeline for compliance, and arrangements for rehabilitation are not luxuries; they are obligations of a humane government.

H.M. Nazmul Alam is an academic, journalist, and political analyst. He can be reached at [email protected].

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments