Lessons we can learn from the recent Teesta disaster

On October 4, the perimeter of the Lake Lonak in India's Sikkim burst, releasing a huge amount of water to the Lachen River (upper Teesta). The river's water level increased by 15-20 feet and destroyed the Chungthang Dam, the largest dam in Sikkim, which was meant to produce 1,200MW of electricity. More than 70 people died, while many remain missing. The damage this incident has brought to the environment and ecology is immeasurable.

The increased flow of Teesta River reached the Indian Gajoldoba Barrage, and its operators opened the gates to let the water flow towards Bangladesh. The Bangladesh Water Development Board (BWDB) officials in turn opened the floodgates of the Dalia Barrage, letting water inundate a large area of the Teesta basin, causing misery for people and destroying their crops, cattle, houses and other belongings.

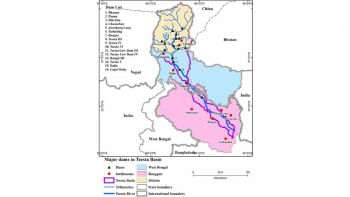

The collapse of Chungthang Dam was certainly catastrophic. However, it was also expected. India already has five dams in operation in Sikkim and is constructing another 13. This small state has the highest number of dams per square-kilometre in India, and aims to produce about 8,000MW of hydroelectricity using the Teesta River and its tributaries. Many in India have argued against this plan, citing Sikkim's fragile and earthquake-prone ecology. However, the private-public consortium pushed ahead and completed the Chungthang Dam in 2017 at a cost of thousands of crores of rupees, overrunning the initial cost estimate by about three times. And all that investment was washed away in a single night.

Bilateral negotiations with India so far have yielded no results in resolving this issue. India continues to hold out the prospect of a Teesta treaty, while building a dozen dams and barrages in upper Teesta to strengthen its control over the river's flow and reducing the flow to Bangladesh in the dry season. The much-talked-about Teesta treaty seems to have become a mirage as Bangladesh wastes its time and energy on false hope.

The lesson for India is clear: it should refrain from its plan of saturating the upper Teesta Valley in Sikkim with dams. A review of the global experience with dams – presented in my recent book Rivers and Sustainable Development – shows clearly that treating rivers as commercial resources, while ignoring their ecological function, is not sustainable. It is necessary to switch to an ecological approach, as some developed countries have already begun doing.

Climate change is pushing this switch to be ever more urgent. Climate change also played a direct role in the recent Teesta disaster. Global warming caused the Lonak Glacier – the source of Lake Lonak – to melt at a higher rate than the rate at which water flowed out of the lake, causing the lake's volume of water to rise. A Glacial Lake Outburst Flood (GLOF) was only waiting to happen, and many experts had warned the authorities about it. Cloudburst rains, the frequency of which is also increasing as climate change worsens, are making GLOFs more frequent. Hence, the recent Teesta disaster was completely human-made. The dam was made by the Indian authorities, and the increased glacial melting was caused by humans in general.

Therefore, India should both reduce its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and stop building dams altogether. But the financial incentives for building dams and barrages are so strong that public and ecological concerns get drowned out. It is difficult to hope that the Indian authorities will absorb lessons from the Teesta disaster.

But what lessons can Bangladesh learn from it? It should be noted that the Gajoldoba Barrage, together with dams in the upper Teesta, has become a double jeopardy for Bangladesh. While they deprive Bangladesh from water flow during the dry season, they cause repeated flooding during the wet months. Flooding now occurs in Bangladesh any time the Indian operators of Gajoldoba Barrage decide to open the gates and release inordinate amounts of water. Before this, flooding was usually a once-in-a-year event for Bangladesh.

Bilateral negotiations with India so far have yielded no results in resolving this issue. India continues to hold out the prospect of a Teesta treaty, while building a dozen dams and barrages in upper Teesta to strengthen its control over the river's flow and reducing the flow to Bangladesh in the dry season. The much-talked-about Teesta treaty seems to have become a mirage as Bangladesh wastes its time and energy on false hope.

Bangladesh first needs to sign the 1997 UN Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses, which forbids upper riparian countries from intervening in international rivers without the consent of the lower riparian countries. It also protects the rights to pre-existing and customary uses of rivers by lower riparian countries and ensures the cooperation of upper riparian countries in protecting the ecosystems of a river, including those of its estuary and adjoining marine areas. Signing this convention will allow Bangladesh to negotiate with India from a stronger, UN-backed standpoint. Secondly, instead of conceding all the transit, transshipment, and port facilities to India unilaterally, Bangladesh could make them conditional with reciprocal steps taken by India regarding the shared rivers. Third, in the short run, we should insist on having a say on the operations of the Gajoldoba Barrage, particularly regarding decisions about releasing water if it is likely to cause flooding in our territory.

Bangladesh also has a lot to do at home. First, it needs to abandon the Chinese moha porikolpona (or "megaplan"), the Teesta River Comprehensive Management and Restoration Project, proposed by the BWDB and aimed at a drastic and sudden reduction of the Teesta River's average width from about 2.5km to only about 0.8km. As researchers have shown, such a change will lead to a drastic reduction in the river's capacity to hold water and will be unsustainable. Instead, efforts should be directed towards expanding the Teesta's water-holding capacity. For this, the river's links with its 12 tributaries and distributaries within Bangladesh need to be revived. In addition, all the ponds, dighis, and other wetlands in the Teesta basin need to be resuscitated and reconnected with the rivers, rivulets and khals. Once this vast network of water bodies is revived, re-excavated, and regenerated, the Teesta river system within Bangladesh will have a huge capacity to hold water, and be able to cope both with the general increase in precipitation and river flow due to climate change and with the sudden releases of water by the Gajoldoba operators. This will also facilitate surface water irrigation during our dry season.

We do need a Teesta megaplan, but not the one that the BWDB is proposing, which will prove ineffective while adding nearly $1 billion to the country's debt burden. Instead, the authorities would be better off entrusting local experts with chalking out a plan. Such an indigenous plan will be both effective and less costly.

Dr S Nazrul Islam is former chief of development research at the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, founder of Bangladesh Environment Network (BEN), and initiator of Bangladesh Poribesh Andolon (Bapa).

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments