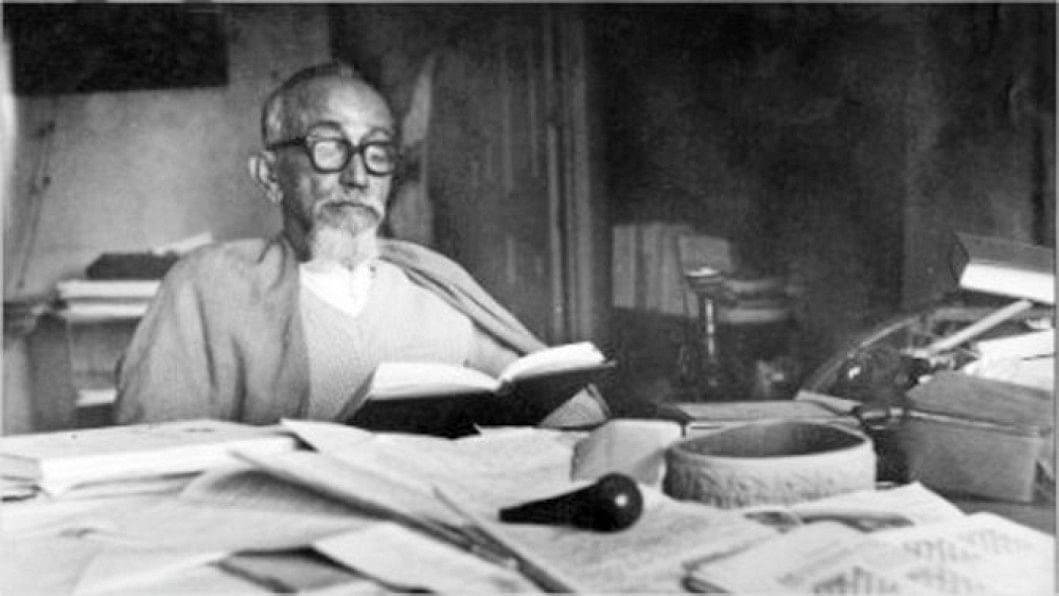

My memories of Prof Abdur Razzaq

About 72 years ago, Prof Abdur Razzaq completed his thesis paper titled "Political Parties in India," which is now in the public domain, thanks to the University Press Limited (UPL). Submitted to the London School of Economics in 1950, the paper delves into contemporary political realities and ideas that were tested in their own time. The writer posited that a sovereign state was essential for the political parties to function. He believed that India needed Westminster-style liberal politics where political parties would be equally invested, whether in government or in opposition. At that time, however, the environment in South Asian countries was not conducive to any Westminster-style politics. Power was concentrated in the hands of a few leaders, while dynasty politics was a dominant influence. Issues like this and much more were explored through the paper.

The belated publication in the form of a book of this now historic paper offers an opportunity to take a look at the man that Razzaq Sir would go on to become, and the long shadow that he would cast over not just his students, peers, the academia and intelligentsia, but also anyone who would come into contact with him, like me.

Prof Abdur Razzaq was known as "Gyantapas" because, in the words of historian Prof Salahuddin, "he spent his entire life learning and pursuing knowledge." Salahuddin further said, "It will not be an exaggeration to call him one of the best symbols of Bangalee intellectualism. He could be called a living encyclopaedia because of his extensive reading of history, social science, economics and so on."

Prof Abdur Razzaq was known as "Gyantapas" because, in the words of historian Prof Salahuddin, "he spent his entire life learning and pursuing knowledge."

He was a humanist and a progressive thinker. Although he didn't like politics, he was drawn to the separatist movement in his early life because he believed that a separatist agenda supporting the establishment of Pakistan was the only way out for the backward Muslim community. But those who subscribed to this view would be in for a rude awakening after the 1947 Partition. Events of those days would profoundly shape the worldview of Abdur Razzaq, who tried to make politicians see the error of their thoughts. During the 1971 war, he didn't leave the country. He was hiding in his village home, and was tried in absentia by the Pakistan military court that sentenced him to 14 years of rigorous imprisonment. After independence, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman designated him as a national professor.

I met Prof Razzaq for the first time at the Dhaka University teachers' lounge, courtesy of my late friend ZM Obaidullah. He was playing chess then. In 1961, I was appointed as a section officer at the finance ministry in East Pakistan. I remember that I went to visit him one day. He wanted to know about my work, so I told him, "Sir, it's quite interesting, although, frankly, I don't understand it much." He said, "Why don't you study economics then?" He encouraged me to pursue higher studies abroad by taking a study leave. This completely changed my career path in later life.

In 1969, between March and October, I was in London on a fellowship. There, I had the chance to meet him again and we grew close. During our conversations, he would often share his thoughts about politics, especially the future of Pakistan. He would say that we needed independence, but he was against having an active military force in an independent Bangladesh. In later life, I went to visit him every time I got the opportunity, sometimes with my friends, including Anisuzzaman, Nurul Huq and Justice Habibur Rahman. Meeting him was a chance to learn. He encouraged us to read. He talked about many things, but was also curious to know our thoughts.

Once, after Sir Fazle Hasan Abed decided to establish Brac University, he thought it would be better to get first-hand knowledge of the university system. So, the three of us visited different American universities to learn about their systems. Upon returning to Bangladesh, I learnt that Prof Razzaq was looking for me. So I visited his house, and told him about Fazle Hasan Abed's initiative. I still remember him saying, with a smile on his face, "Ask Abed to establish 100 good schools instead of one university. The country will be better served in this way." Many may not know that Razzaq Sir himself wanted to establish a school in Dhaka. He even selected three scholars who would join the school: Badruddin Umar, Sardar Fazlul Karim, and Anisuzzaman. But it didn't pass the planning stage for some reason.

I have so many memories like this of Prof Razzaq. He was truly a gold mine of knowledge and resources. He would often share his insights about the history of the subcontinent, especially major political events and trends that shaped its future. He was keenly aware of the socio-political history of Muslims in India. Once he was talking about the 1905 Partition of Bengal, a territorial reorganisation of the Bengal Presidency that was revoked a mere six years later. The short-lived break, according to Prof Razzaq, was part of the "divide and rule" policy of the British, which they sought to pursue in many other areas as well. In 1911, the British, in the face of protests, assented to reversing the decision. It was also decided that India's capital would be shifted to New Delhi, although that decision couldn't be implemented immediately. Infrastructure development and other changes befitting a capital were halted because of World War I. The capital remained in Calcutta, and was finally shifted to Delhi in 1931, he said.

I also remember that Razzaq Sir once presented a written speech titled "State of the Nation" in 1980. It was his only written speech, later published in 1981. I had the good fortune of listening to his speech live. It was divided into two parts, the first involving a discussion on economics and politics. In it, Razzaq Sir said Bangladesh's assets were its land, people, unique geographical location, rivers as well as their effects in agricultural production. The present government's Delta Plan 2100 is, in a way, a reflection of Prof Razzaq's thoughts shared in his 1980 speech.

In the speech, he also talked about the divisions brewing in politics ever since independence, saying, "What holds us together, makes us a nation, is the exclusive passion to identify ourselves with this nation – and nothing else." He also said, "The prosperity of Bengal was never dependent on its agriculture but its trade and commerce, and the products of handicrafts and small-sized enterprises." To further explain this idea, he asked, "Why did traders from the Middle East come to Bangladesh?" and then proceeded to answer: it was because of its trade and the economic benefits it offered to them.

Thus, in public interactions or private, Prof Razzaq spread his love of knowledge and passion for intellectual exercises, never hesitating to encourage us to read and think. It seemed only befitting that Badruddin Umar once proposed that we call him Bengal's Socrates. I asked him why, to which he replied, "Even though he didn't write, he spread knowledge by encouraging others to learn and think. Like Socrates, his teaching method was also verbal."

He truly was our Socrates.

This is based on a speech on Prof Abdur Razzaq presented on the occasion of the publication of his book "Political Parties in India."

Translated from Bangla by Badiuzzaman Bay.

Md Syeduzzaman is former finance secretary and finance minister of Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments