New curriculum is detached from reality

The recent introduction of a new school curriculum has stirred controversy among all parties involved. But instead of addressing the concerns raised by these parties, the government has taken a hard-line approach, resulting in the arrest of some parents. Criticism of the curriculum has been silenced using various tactics. Even Dhaka University teachers were not allowed to hold a discussion on the new curriculum. It is surprising how the government has reacted, as this could have been an opportunity for them to use stakeholders' inputs and improve the curriculum further.

The government claims that the old curriculum created dependence on coaching centres, guide books, memorisation, and examinations, whereas the new curriculum has been created to free education from these. We have been saying for a long time that our education system exerts too much pressure on students. There is the pressure of textbooks and exams, while the reliance on guide books and coaching centres has gotten to an extreme state. We wanted changes so that students could feel the joy of learning, instead of it being a source of pressure year-round. So if the government is trying to solve these problems, we can appreciate the steps involved. However, the manner in which the new curriculum is being implemented raises the question of whether this would further complicate old issues instead of resolving them.

Everything that the government has said about the old curriculum is true. But the question is, who introduced that curriculum? This government has been in power for a long time, and the curriculum that they are criticising now was developed by them. Last time, too, the government claimed that the new "creative curriculum" would solve the guide book issue, reduce cheating in exams, and remove the need for private tuition. Clearly, none of those happened.

This government's 2010 education policy proposed primary education up to Class 8 and secondary education up to Class 12. This was not implemented, either. Instead, things that were not mentioned in the education policy, such as board exams in Classes 5 and 8, were implemented. It is because of this increased number of exams that the business of guide books and coaching centres flourished.

Another reason given by the government is that other countries that have implemented such curriculums have seen widespread success—for example, Finland and Japan. Yes, they have very good education systems. But the context of these developed nations and that of Bangladesh are so different from each other that we need to make drastic changes in several fields to fit into the category of these countries.

First of all, none of the countries mentioned have so many different streams of education as Bangladesh does. We have Bangla medium schools and colleges following the national curriculum, which also have English versions—this is the mainstream education system. Then we have English medium schools, and madrasas—Qawmi, Aliya, and English medium cadet. Then, among English medium schools and madrasas there are highly expensive ones and less expensive ones. Inequality and deprivation are major features here.

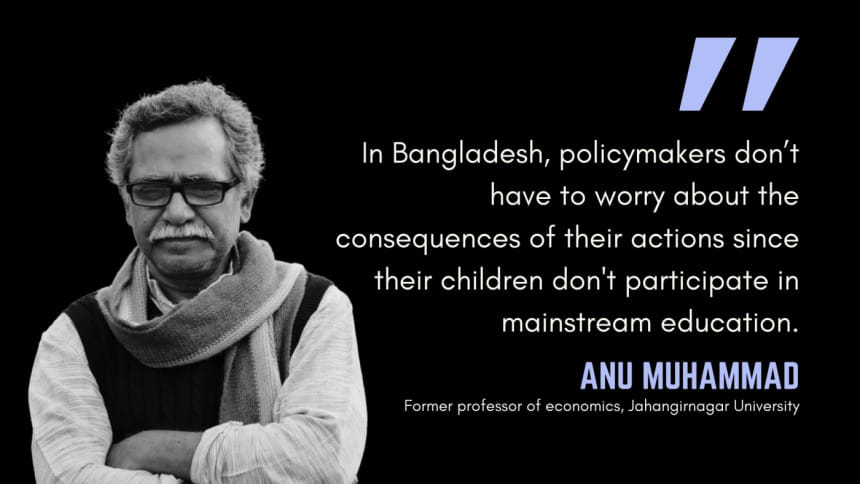

Second, in Bangladesh, policymakers don't have to worry about the consequences of their actions since their children don't participate in mainstream education. They go to either English medium schools or abroad for education. Thus, the decision-makers themselves are not as connected to the mainstream education system as they should be.

In countries like Finland or Japan, education is free for all citizens. There is no scope for any profit-hunting businesses to operate in this sector. From books to electronic devices, including computers, to transport like school buses—everything is provided for; thus, the cost of education is not something students or guardians have to be concerned about. But in Bangladesh, whenever there is some sort of policy-level change, the financial implications for those who are going to be affected by that change are extremely important.

There is also a big difference in the teacher-student ratios. The successful countries have a teacher-student ratio of around 1:20 to 1:25. This is unimaginable in Bangladeshi mainstream education, where we see 50 or 60 or even 100 students per teacher. These other countries also have the most updated and developed infrastructure in education, while our schools and colleges lack proper laboratories, libraries, sufficient number of teachers, regular training, etc. Thousands of teaching posts are kept vacant despite high demand.

In countries like Finland, teaching is one of the most attractive, dignified, and well-paying professions. Primary school teachers are treated with a great amount of importance and respect as they create the foundation for the new generation. In contrast, our teachers' salaries are so low that they cannot even survive without other jobs, including private tuition, commission from guide books, etc. Teachers are paid poorly even in government schools in Bangladesh. Non-government teachers are suffering from absolute poverty and they recently staged a hunger strike to demand proper wages.

Those other countries devote a huge amount of time and resources to the teachers, students, and other parties involved in making any changes. They invite different opinions and improvise over time to find the best solution for all. What is happening in Bangladesh is a top-down approach: a decision has been made and the required action has been imposed upon all. Discussions or suggestions are not being welcomed.

Considering all these facts, if we want to appropriately improve our education system, we have to first look at the reality. Without addressing fundamental problems like low salaries of teachers, poor infrastructure, shortage of teachers, high student-teacher ratio, and multiple streams of education, imposing a completely new curriculum will only create more problems and confusion.

So, the educational infrastructure has to be reformed, new teachers have to be employed, and the pay structure and benefits for teachers must be upgraded. Teachers need to have a comfortable enough income so they don't have to look for other sources of income. Additionally, opinions of teachers, students, and guardians need to be taken into account when a curriculum is designed so it can be truly inclusive and actionable. Given the current state of the government initiative of an experiment with millions of students, we are looking towards a potential repeat of the old results.

As told to Monorom Polok of The Daily Star

Anu Muhammad is a former professor of economics at Jahangirnagar University.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments