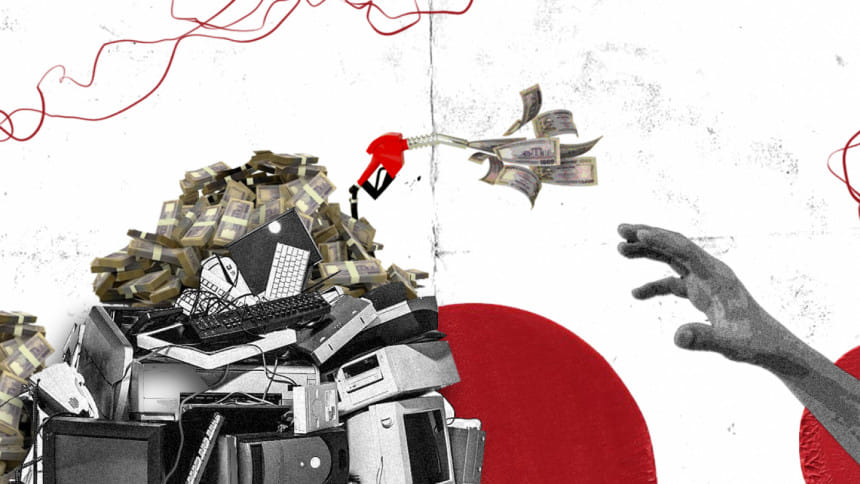

Is policy failure to blame for our wage inequality?

The phenomenon of access to new technology resulting in skills gaps and wage inequality is visible in all economies; and so is the rising trend in poverty, particularly among the ageing population in developed economies. So, companies counter this by hiring a skilled workforce from foreign countries. This issue is discernible in all age groups due to the existence of poor quality education in developing countries, which policy-makers are to be blamed for. They feel that grooming workers in light of new technology will fail because it requires too much time, effort, and money. Quite unusually, the education and course curriculum quality in the concerned countries remains the same, with an increasingly unemployable workforce that has no hope of escape.

How do we enhance access to upskilling? Take the case of East Asian countries. Given its multilevel focus and private sector collaboration, the region's acclaimed skills development system exemplifies concerted national and integrated efforts. The region is successful because it is linked to the various nationwide policies within it (related to economic development and technology transfer) and different institutions are able to work together.

Does wage inequality exist in Bangladesh due to policy failure? Studies show that widened wage gaps and unemployment rates due to the inaccessibility of technology can be observed in developed and developing economies alike. Reportedly, the demand for skilled (as opposed to unskilled) labour has increased relative to their supply. The concept of skilled labour can broadly be divided into two groups: those assuming skill-biased technological change is exogenous and those thinking that adopting skill-biased or unskilled-based technologies is endogenous. The overwhelming majority of studies belong to the first group, who have argued that skill-biased technological change has played a central role in increasing inequality in recent times.

High levels of inequality reduce growth in relatively poor countries but encourage growth in more affluent countries. Economist Robert Barro studied a broad panel of countries between 1960 and 1995 and found that growth tends to fall with greater inequality when income per capita is less than $2,000 (in 1985 dollars) and rises with inequality when income per capita is more than $2,000. He concluded that income-equalising policies might be justified to promote growth in poor countries. For more affluent countries, however, active income redistribution appears to incur a trade-off between the benefits of greater inequality and a reduction in overall economic growth. Barro further showed that the overall relationship among income inequality, growth, and investment is weak. He investigated the effect of economic development on inequality and found that the traditional relationship here is the Kuznets curve, which describes an inverted U-shaped relationship between inequality and growth: inequality first increases and later decreases in economic development. Economist Simon Kuznets explained this in terms of a shift from the rural/agricultural sector of the economy to the urban/industrial sector.

This type of relationship also emerges in Barro's analysis. However, the curve likely reflects not only the influence of the level of income per capita but also the effect of adopting new technologies. The poor sector uses old technologies, whereas the prosperous sector uses more advanced techniques. Technological innovations (including the factory system, electric power, computers, and the internet) tend to raise inequality when only a few people initially share in the relatively high incomes of the advanced sector. Eventually, however, inequality falls as more people take advantage of new technology. Overall, for poor countries, the escape from poverty becomes more difficult because rising per capita income induces more inequality, which retards growth in this range. Experts argue that such a decline may be due to the failure to create an ecosystem for quality education.

Notably, most newer technologies entering the market through more unique products and processes are skill-biased because they use skilled workers more intensively than the older technology. Experts have found that the relative supply of skilled workers concentrates the adoption of new technology to a specific region—those having a higher supply of skilled labour are likely to be quicker in adopting new technology. Likewise, while the real wages of skilled workers are expected to increase as new skill-biased technology is adopted, the wages of unskilled workers may either remain unaffected or even fall. The issue of the supply of skilled labour has become an area of immense interest mainly because of the rising inequality in the relative wages of skilled and unskilled labour.

Consider Bangladesh. It has a large workforce, but Bangladeshi employers often hire foreign nationals because they feel locals require more skills. Migrant workers from countries like India, Sri Lanka, and the Philippines can negotiate higher wages because their abilities are recognised. Anyone can see the absurdity in hiring thousands of experienced textile engineers at minimum wage to produce high-quality products. The problem is not a shortage of professional textile engineers; the problem is that the country's economic decision-makers cannot understand growing demand. It is to be noted here that Bangladesh also has immense prospects as a role model for manufacturing. The fact is that foreign investors' friendly policies don't mean that one expects an unlimited supply of plant managers or well-trained technicians to line up at their door. Besides, they cannot access whatever labour they need at their chosen wages.

It is often argued that capitalism generated extensive prosperity for centuries by rewarding the most productive uses of available work. As Adam Smith postulated in The Wealth of Nations, "...every individual naturally inclines to employ his capital in the manner in which it is likely to afford the greatest support to domestic industry, and to give revenue and employment to the greatest number of people of his own country…"

Theoretically, access to technology and innovations are size-neutral. The blame is with policy entrepreneurs who created this size bias due to their jerry-built knowledge. Thus, wage inequality and poverty are the consequences of the awful human resources policy they have adopted.

Arindam Banik is designated visiting professor of ICCR's Chair in Indian Studies at Samarkand State University, Uzbekistan.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments