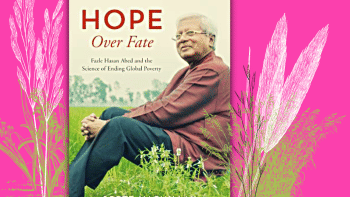

Remembering Sir Fazle Hasan Abed: A life fulfilled

I first met Fazle Hasan Abed at Oxford, though our paths had briefly crossed before. At the time, he was an executive at Shell in Chattogram, a position that placed him within a distinct social circle. However, Abed had already begun to transcend those boundaries. Mutual friends, Viqar and his wife, had spoken to me about his involvement in relief efforts following the devastating cyclone of 1970. He had mobilised a group of like-minded individuals to address the crisis, which deeply impressed me. Here was a corporate executive stepping beyond his domain to directly engage with a national tragedy.

Unbeknownst to me, Abed's commitment was only deepening. When the Liberation War erupted, he made the remarkable decision to resign from Shell, relocate to London, and immerse himself in the cause. London was a hub of activity for the liberation movement, with numerous groups working under the leadership of Justice Abu Sayeed Chowdhury. The environment was fragmented, with each faction pursuing its agenda, often casting aspersions on others' motives. It was in this complex setting that I reconnected with Abed.

Abed sought me out at Oxford, accompanied by his close associate Marietta. They were actively channelling resources to those affected by the genocide in Bangladesh. His approach was twofold: immediate relief and long-term planning. Even amid the uncertainty of July-August 1971, Abed was optimistic about liberation and was already contemplating the kind of society we would want to build in a free Bangladesh.

Our discussions were speculative as the future of Bangladesh remained unclear. The economy was in disarray, and the social fabric had been torn apart by war. Yet, what stood out to me was Abed's determination to become a catalyst for change. He belonged to a new generation that sought not merely to envision transformation but to actively participate in it.

After liberation, Abed returned to Sylhet. There, he embarked on what can only be described as a revolutionary journey, immersing himself in rural Bangladesh—a stark contrast to his previous corporate life. The challenges were immense: a shattered economy, devastated communities, and a nascent government struggling to take shape. Yet, through trial and error, Abed persevered. Whether experimenting with microfinance, initiating one-room schools or rebuilding livelihoods, he was guided by a singular principle: bringing about incremental, sustainable change. His work in Sylhet laid the foundation for BRAC, which would go on to become the world's largest NGO.

Each step Abed took was original and daring. He did not merely adopt tried-and-tested methods; he invented new pathways. His approach to microfinance, for example, emerged as a pioneering model that would eventually uplift millions. Yet, not all his experiments succeeded. The deep tube-well programme, which aimed to empower the landless by enabling them to sell water to landowners, faltered due to the entrenched power hierarchies in rural Bangladesh. Still, Abed's willingness to take risks, adapt, and learn remained unshakeable.

I vividly recall his support when I sought to establish the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD). The idea was modest: to create a platform for public discourse and policy innovation. Abed was among the first to back the initiative, contributing generously and without hesitation. His commitment to fostering dialogue and intellectual growth was emblematic of his broader vision: encouraging systemic change through collective effort and shared knowledge.

One defining aspect of Abed's leadership was his adaptability. He understood that sustainable development required innovative, self-sustaining models rather than perpetual reliance on donor funding. He was acutely aware of shifting donor priorities and adept at aligning BRAC's initiatives with emerging trends.

An illustrative example was the one-room schoolhouse initiative. My cousin, Kaniz Fatema, was involved in this project, which drew inspiration from successful models in Pune, India. Abed strategically delayed scaling up the programme until education became a priority for the donor community. When the time was right, he secured significant investments, transforming it into a cornerstone of BRAC's work.

Abed's entrepreneurial spirit extended beyond BRAC. He understood the importance of aligning his initiatives with global trends and donor interests. When the world's focus shifted from microfinance to education in the 1990s, Abed capitalised on the moment. His one-room school project, which began as a modest experiment, grew into a cornerstone of BRAC's educational endeavours.

Abed was more than a social entrepreneur; he was a visionary leader who could have excelled in any corporate boardroom. His business acumen, coupled with an unwavering commitment to social justice, made him a transformative figure. He was a pioneer of social entrepreneurship, demonstrating that impactful change could be achieved through innovative, sustainable practices. His initiatives improved the lives of millions, not only in Bangladesh but globally.

What distinguished Abed was his relentless pursuit of fulfilment. He derived satisfaction not from wealth or accolades, but from the tangible impact of his work. By the time of his passing, Abed had touched countless lives, leaving behind a legacy of hope and progress.

In reflecting on his life, I am struck by the profound sense of accomplishment he must have felt. Fazle Hasan Abed departed this world as a fulfilled human being—a rare and extraordinary achievement. His life serves as an enduring inspiration, reminding us of the power of vision, resilience, and unwavering commitment to the greater good.

Prof Rehman Sobhan, one of Bangladesh's most distinguished economists and a celebrated public intellectual, is founder and chairman of the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD).

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments