The hydro-hegemony in South Asia

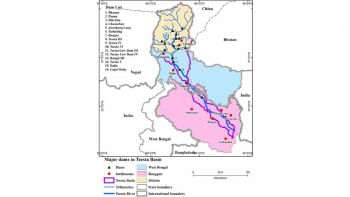

The West Bengal government recently decided to dig two new canals to divert water from the Teesta, a transboundary river that India shares with Bangladesh. Water from another transboundary river, Jaldhaka, will also be channelled to the canals for agricultural purposes. The canals are expected to benefit 100,000 farmers in Jalpaiguri and Cooch Behar, and the West Bengal Irrigation Department has already been allocated 1,000 acres of land for the canals under the Teesta Barrage Project.

However, the benefits will come at the expense of Bangladeshi farmers in northern Bangladesh. As Teesta is a transboundary river, both Bangladesh and India should share its water in an equitable and reasonable manner, as per the international water-sharing convention. Unfortunately, Bangladesh has been denied such equity and reason as upper-riparian India unilaterally constructs barrages, dams, and canals, restricting the river's flow to Bangladesh.

This has also resulted in a scarcity of river water, with only 100 cumecs (cubic metres per second) available during the dry season, compared to the 1,600 cumecs required for agriculture in both countries.

Bangladesh and India share 54 rivers that flow from the Himalayas to the Bay of Bengal. The best practice across the world is to manage such international or transboundary rivers in accordance with international rules and conventions such as Helsinki Rules, Berlin Rules, and the 1997 UN water-sharing convention. But in South Asia, this takes the form of bilateral agreements between the relevant stakeholders. As a result, the upper-riparian countries often enjoy advantages and unequal shares. For instance, India's construction of canals and barrages affects Bangladesh adversely. In the same manner, India also faces the same issue with China in the case of Brahmaputra River. As a result, Bangladesh has managed to get India to sign agreements on only two rivers: the Ganges and the Kushiyara. The Kushiyara agreement came nearly 25 years after the Ganges River treaty. Decade-long negotiations have failed to ink the treaty on Teesta water-sharing.

The delay in signing the Teesta treaty and the uneven water distribution have resulted in serious environmental and agricultural concerns in northern Bangladesh, where the river is drying up, biodiversity is under peril, and food production is being adversely affected. Between 2006 and 2014, the northern region of Bangladesh, known for its ample Boro rice harvest, lost Tk 8,132.6 crore in production due to water shortages caused by India's arbitrary withdrawal from the river.

Why has the water-sharing deal stalled when both Bangladesh and India have built much more fruitful relationships in other areas? The answer probably lies in the concept of hydro-hegemony.

Hydro-hegemony is a relatively new theory that argues that water-sharing, conflicts, and river management between the countries that share transboundary rivers are influenced by their riparian position, power dimensions, and exploitation potential. Prominent Indian scholar Brahma Chellaney used the term to explain China's activity in the upstream that affected India. In the case of Bangladesh-India transboundary rivers, India holds the upper hand as the country is upper-riparian. When India has a demand for river water, it can simply dig canals and redirect the river's flow, or build a barrage to navigate the water flow.

Bangladesh lacks the political and economic power to force India to provide its rightful share of water. Because of this power asymmetry, India influences the negotiation process often in its favour. The decision to drain water from Jaldhaka River without informing Dhaka is a prime example of such influence. Not only that, but India consciously depoliticises bilateral disputes between the two countries.

India also gets to exploit Bangladesh based on its technological projects. Historical water flow data suggests that Bangladesh's share should not fall below 4,500 cusecs (cubic foot per second), but India's upstream interventions with technologically advanced barrages have decreased Bangladesh's share to one-third of that amount. Similar riparian and power dynamics have harmed India's equation with China over water-sharing on the Brahmaputra. The river is shared by China, India, and Bangladesh, but because China is upstream, it can build dams and barrages that threaten water flow to India and Bangladesh in the absence of any treaty. While India narrates China's behaviour as unequal, interestingly it does the same with lower-riparian Bangladesh.

River disputes will persist in South Asia because the region's largest rivers – the Indus, Ganges, Brahmaputra, Teesta, Mahananda, Surma, and Ghaghara – are transboundary. The region is largely dependent on these river basins. As a result, disruption and unjust water flow can lead to conflicts. Brahma Challaney in his book Water: Asia's New Battleground also discussed such.

War or conflict for water has been going on for ages. For decades, conflicts between Egypt and Ethiopia often escalated over the Nile River's water-sharing. Water also played a central role in the civil war in Sudan. Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon also had a series of confrontations with Israel in the 1960s over the Jordan River that ultimately culminated in the Six-Day War.

In the case of Bangladesh and India, river basin management has been always suggested to avoid such conflicts. But for that, the upper-riparian side must acknowledge equity and reason. Yet, the hydropolitics between Bangladesh and India can be of great interest to researchers as it has unique hegemonic elements in river management. How the upper-riparian and its federal governance structure is posing challenges to the lower-riparian is quite a new phenomenon in hydropolitics. Therefore, researchers may take a keen interest in developing further understanding.

Masfi-ul-Ashfaq Nibir is a Dhaka-based independent researcher and analyst.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments