An urgent call for environmentally sustainable computation

In recent years, the promise of artificial intelligence (AI) has fascinated technologists and the general public alike. The potential to learn, predict, and simulate through machine learning, especially large language models like GPT-3, is indeed captivating. However, these digital marvels come with a hidden cost: water.

Yes, you read that correctly. Our AI companions are water guzzlers.

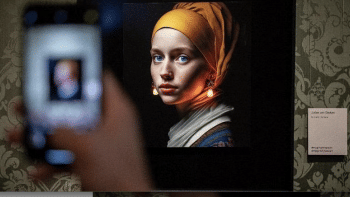

Using a tool like ChatGPT can be as refreshing as a dip in a pool on a hot day, especially when it provides a customised line of code you have been seeking for hours. But just as you might be surprised to find that the pool had to be refilled after your swim, you might also be astonished to discover that a 15-minute conversation with your AI pal has potentially consumed about half a litre of freshwater.

At first, this might seem counterintuitive. Why would AI, a purely digital entity, need water? As revealed in a recent research paper titled "Making AI Less 'Thirsty': Uncovering and Addressing the Secret Water Footprint of AI Models," by Li et al., it turns out that tech firms utilise vast amounts of water for AI training and running inferences on their massive computational firms.

The intense computation required for AI training produces significant heat, and to dissipate this heat, firms use cooling towers where water is evaporated. This process, consequently, is how AI guzzles up water – freshwater, to be precise.

The paper estimates that training a model like GPT-3 in Microsoft's state-of-the-art US data centres could directly consume 700,000 litres of clean freshwater. If the training occurred in Microsoft's Asian data centres, this consumption would triple.

Even more staggering are the water implications of AI usage. For example, in June 2023, an estimated 1.6 billion user visits were recorded on ChatGPT. If every interaction consumes half a litre of water, we are looking at hundreds of millions of litres of freshwater used every month just to power our digital conversations.

As AI becomes woven into more apps and devices, this usage and consequent water consumption is set to rise dramatically. Soon, AI-powered banking interactions, website interfaces, e-commerce, and even mundane household tasks will be commonplace. As a result, water consumption will rise in tandem, putting more strain on our already limited freshwater resources.

Addressing this mounting water crisis requires a multifaceted approach. The authors of the study propose that tech firms could alter their training times to periods of lower heat, thus reducing water demand. However, this might conflict with carbon reduction efforts, as solar power is most readily available during the hottest part of the day.

In this situation, civic and public pressure can play a crucial role. By implementing appropriate water pricing strategies, cities and states can incentivise tech firms to reduce their water consumption. Indeed, much like energy efficiency improvements at data centres over the past decade, increased attention and pressure could induce radical improvements in water usage efficiency as well.

There's no silver bullet solution here; the problem is as intricate as it is urgent. Tech firms, who have pledged to become "water positive" by 2030, are looking into strategies such as rainwater collection and "adiabatic cooling" that uses air instead of water. But even with these interventions, the predicted savings are dwarfed by the scale of water consumption by AI models.

However, this progress would only be a drop in the bucket compared to the broader challenge of water scarcity. AI's water footprint may be the tip of the iceberg, but it is an indicator of a larger, looming crisis. As our digital thirst grows, we need to ensure it doesn't leave us high and dry in the real world. It is time for all stakeholders – tech companies, governments and consumers – to address the hidden water costs of our digital companions and move towards truly sustainable AI.

SM Mashrur Arafin Ayon is a postgraduate student at the University of Dhaka with interest in intersections of gender, technology, and feminist theory.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments