Viewing the defaulted loan saga through a micro lens

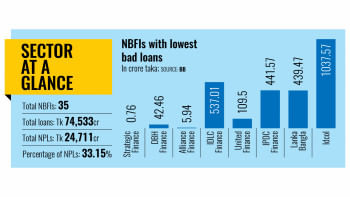

Over the years, the volume of non-performing loans (NPLs) in Bangladesh has increased so significantly that it has become a major reason for Bangladesh's economic woes. According to the recent data of Bangladesh Bank, NPLs rose to a record Tk 284,977 crore in September 2024, surpassing the earlier record of Tk 211,391 crore just three months prior, making up around 17 percent of the total outstanding loans.

The increasing trend of NPLs can be attributed to several factors, including poor governance, inadequate business and industry analysis, political influence, and the borrowers' inability to repay debt due to internal economic conditions, all of which are widely recognised even to a layman. Instead, let's look into whether the defaulted loan culture has evolved into an institutionalised practice at the micro level that ultimately translates into a higher NPL ratio at the aggregate level.

A brief introduction to institutional economics is needed to delve further into this discussion. Institutional economics encompasses a broad idea of institutions beyond what we typically understand. Rather, it deals with formal and informal institutions; officially recognised rules and written laws and regulations formulated by the government, organisations and other formal entities fall under formal institutions, and socially constructed rules and norms, customs and traditions, and unwritten ethical standards are viewed as informal institutions. Briefly, institutional economics explores how laws, regulations, social norms, customs and organisations shape and influence economic behaviour and outcomes.

In light of this framework, a link can be established between informal institutions at the micro level and the prevalence of NPLs at the macro level, questioning whether the practice of defaulted loans has become ingrained deeply enough to be considered an institution.

In the context of Bangladesh's economy, if we look around, the retail-level demand and supply are largely met through informal mechanisms, with most transactions occurring outside of established formal institutions, without any receipt. This serves in the interest of both consumers and sellers, who often benefit from the leverage provided by asymmetric information. As a result, the lack of evidence of transactions heightens the potential for both consumers and sellers to engage in deceptive practices.

For instance, in the absence of formal institutions, a sense of trust often develops between customers and sellers in grocery stores and road-side tea stalls. This trust enables smoother transactions, allowing consumers to acquire their desired products without paying the full amount upfront while giving sellers confidence in securing a sale, thereby reducing risks for both sides. At first glance, this may appear to be a positive phenomenon, as trust fosters regular transactions that contribute to economic growth. However, on the flip side, the lack of evidence for these transactions, such as receipts or written documentation, creates a chance for consumers to avoid repaying the money after fully maximising the utility from the product they have consumed. At micro level transactions, the story of defaulting starts simply from here.

Although specific data on this type of mismatch in micro-level transactions is unavailable, the above-mentioned scenario is one that almost anyone can relate to through their day-to-day experiences. Another common example, frequently featured in the media, is students with political ties who fail to make timely payments at their universities' cafeteria and other shops on the campuses. One report from last year cited how a student with political affiliation was suspended for allegedly attacking the cafeteria owner at a residential hall in Dhaka University for requesting the payment of dues amounting to Tk 2,650.

The habit of not paying back the promised amount after receiving a service has become so deep-rooted at the micro level that people no longer think much of it. It suggests that the reluctance to make payments has already become a norm, to the point where it can be considered an institution, according to institutional economics. Just as political influence on campus is used to avoid paying debts, and trust is overlooked when it comes to settling dues at the micro level, political influence prevents good governance from acting as a safeguard against the rising amount of defaulted loans at the macro level. Is it merely a coincidence that the dynamics observed at the micro level are mirrored at the macro level?

This is the question policymakers must explore to determine if defaulting on loans has already become an institutionalised practice. The similarity between avoiding payment at the micro and macro levels should not be overlooked. If loan-defaulting has indeed become institutionalised, addressing NPLs requires a whole new approach, confronting the core issue. In order to do that, mismatches in smaller-scale transactions should not be ignored. Last but not the least, taking steps to foster an ambience of goodwill in the micro sphere could create an institution capable of deterring the practice of loan default and NPLs in the macro sphere.

Tahsin Sahriar is assistant director (research) at the Bangladesh Bank.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not reflect that of his employers'.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments