VIP movements are Dhaka’s undiagnosed illness

"Is there something going on today? Been stuck at Panthapath Signal for 35 minutes."

"Avoid Mohakhali."

"Avoid Uttara."

"If they are indeed VIPs, why can't they just use helicopters and leave the roads for us?"

"Don't hit the road today unless it's a life-or-death situation."

"Avoid Dhaka."

These are some of the quips and complaints repeated on Dhaka-centric citizens' forums on Facebook daily. The tragic, honest-to-God truth is that Dhaka is nobody's jaadur shohor. It hasn't been so for a while. And despite many developments, city life only seems to be getting worse for the lot of us.

The single task of commuting from any one place of the city to another is costing us incredible amounts of time, energy, and motivation. Worse still, it's not just the isolated feeling of a handful of citizens. One recent study by US-based National Bureau of Economic Research found Dhaka to be the slowest city in the world, out of 1,200 cities in 152 countries. For further clarity on the issue, last year, the World Bank alongside Buet's Accident Research Institute found that the average speed of vehicles in our capital had dropped to 4.8km per hour, from being 21km per hour in 2007.

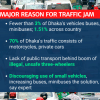

We must be doing something terribly wrong if, after so much infrastructural development through so many megaprojects—not to mention funds spent in tens of thousands of crores—our traffic congestion has only gotten worse. Sure, one could argue that the country has developed so well that too many people own cars now. And indeed—the unaffordability of eggs, potatoes and cooking oil aside—more roads have also been built all across the country. Still, how come we can't seem to catch a breather from traffic congestion?

Well, for one, it is an age-old fact that more roads never equal less congestion. As the phenomenon of induced demand goes, building more roads in a still-growing city like Dhaka will only prompt more people to get cars and make use of the new roads. Add to this the dismal state of public transport in the capital, and it remains no wonder that our traffic situation stands where it does.

None of this is news. But there are still two types of people who must be unaware of how much worse Dhaka's traffic situation has gotten over the past few months: 1) a Dhakaite who rarely or never has to commute between 7am and 11pm; and 2) someone who is considered a VIP by the authorities. While I—and millions of others—envy both, the treatment given to the latter understandably boils the blood of most sensible citizens.

A bad case of traffic jam, in itself, can exhaust even the most patient of human beings. But when whole sections of a very busy city—the capital of this country, no less—are deliberately put into a standstill, just so the fancy fleet of vehicles guarding one or a few people can pass through the roads in one go, the rest of us waiting in cars, muggy buses, on bikes, or standing on the roads can't help but feel utterly dehumanised. For this to happen multiple times a day, for weeks on end—as we have witnessed lately—is quite telling of how worthless the people are in the eyes of those who are in charge of us.

Over the last couple of months and to this day, I have read numerous citizen accounts of sufferings during VIP movements on social media: people claiming to have been stuck in one spot of traffic for over an hour; active ambulances being delayed by a VIP movement; students missing crucial exams due to traffic being halted without notice to let one minister or some dignitary pass. Of course, being forced into a standstill, many opt for reaching their destinations on foot. But with no thanks to the planners of our capital, being a pedestrian in Dhaka is no cake walk. Having to walk on roads and footpaths made up of what can only be described as loose gravel, while trying to not fall into an open drain, really hammers into us the horrifying unliveability of this city we so want to love.

My worst realisation of late has been that most of the public feels helpless. A few weeks ago, when the heat was still unbearable, I was standing in line for the bus home. It took about 15 minutes of waiting for me (and others queued up) to realise we'd probably be standing for 15 more, or even longer. It was the worst: a dreaded VIP movement.

And the congestion caused by VIP movements is distinct, in that there is no honking. There is an odd, eerie quiet all around, even with hundreds of vehicles and thousands of people stuck in one place for so long. Some, feeling defeated, eventually exit their vehicles to simply walk around the scene for a bit. For those of us waiting in line for public transport, we can only shift our weights from one foot to another, and back, for 30 minutes to an hour or longer.

On the aforementioned evening, when I was characteristically complaining about the situation to whomever was in front of me in line, I realised that everyone seemed too exhausted to even be upset about the huge inconvenience caused by the VIPs. I listened in on a few conversations around me, hoping that some anger would spark through. But this much became clear: people in Dhaka are so consumed with simply trying to have a decent livelihood that they barely have any heed left to pay to what our political overlords are getting away with doing to us.

And it's the same with everything. We don't feel in control of the prices of food or fuel. All we feel we can do is comply. The "authorities" seem like a machinery so removed from us and so untouchable that we have forgotten about them. We have forgotten that it is we who should be able to hold them accountable: for the VIP movements, for the broken roads, for the overpriced and prolonged megaprojects, for the price inflation of essential food.

But we cannot and must not lose our rage. The powerful exerting their power is only one half of the undemocratic equation. The other half requires regular citizens to comply with whatever is pushed onto us—as if we aren't in a democracy. We must never give this compliance to the authorities.

As with any feeling that is best felt deeply, respect cannot be taught in textbooks, incurred through PR moves, or extorted with threats. The true respect of an entire people must be earned by our government, if they really want it to be long-lasting and not change hands as power does (if it is ever allowed to). All number of bridges, railways, flyovers, and other megaprojects built by a government lose any significance for the average citizen when we are forced to wait on the road, in the heat, for an hour or even longer after an already excruciating work day, only so those whose luxuries our tax money pays for can always be comfortable on the other side of the traffic congestion we live and breathe in. It is the everyday things that the government pays no heed to that can tip the balance strongly against them, come ever that much-anticipated free and fair election.

Afia Jahin is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments