More roads are not the answer to Bangladesh’s traffic problem

That evening, it rained and it rained, and then it rained a little bit more. A group of friends were returning from the beach town of Cox's Bazar on a microbus. As rain dribbled down on the window panes, everyone settled into their seats for the journey ahead. One-third of the way out, the group got stuck on a flyover in the port city, for seven whole hours. Why? The downpour had inundated the city below, and bumper-to-bumper traffic lay ahead. There was no choice but to ride out the rain on the flyover – incidentally one that had been constructed to tackle traffic jams. The wait was so long that one of the passengers had to fashion a holder out of a bottle to relieve their bladder. The bottle was left on the curbside; slowly filling to the brim with urine. I have been told that the group watched – in horror and some amusement – as it filled up with water, mixing with human excreta, to eventually spill onto the road.

An excruciating 19 hours on the road to complete a 251 km journey, then three more hours to get to Dhanmondi from Uttara, or the regular peak-hour traffic that sucks out our will to live, are commonplace in a Dhaka resident's life.

The city with a population of nearly 4.5 crore people has one of the highest population densities in the world. To accommodate its exponentially growing population, the capital too has grown on all fronts. The pro-development ruling party has altered the cityscape during its lengthy tenure. The elevated expressway is starting to take shape, the roads around the airport have changed, many U-loops have been inaugurated, the Metro Rail is no longer a far-off dream, and all the flyovers around Pragati Sarani and the one in Kalshi (promising to take you to the airport from Mirpur in 15 minutes) were also constructed during this government's tenure.

Many of these projects were undertaken as a means to cure Dhaka of its traffic problems. After all, for years everyone kept saying the big problem was that we did not have enough roads. Chattogram, too, has experienced a similar flurry of construction specifically focused on improving its road network. Despite these interventions, people still get stuck on flyovers for hours, couples still think one of them living in Uttara and another in Mohammadpur is akin to being in a long-distance relationship, and the country – deep in the throes of an economic crisis – continues to lose a few billion dollars in GDP each year to traffic. In fact, the economy lost Tk 56,000 crore in 2020 due to traffic, according to the Accident Research Institute (ARI) of Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (Buet). A previous study by Brac Institute of Governance and Development (BIGD) revealed that traffic congestion in Dhaka eats up around five million working hours every day and costs the country $11.4 billion each year. The financial loss is a calculation of the cost of time lost in traffic congestion and the money spent on operating vehicles for the extra hours.

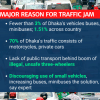

Our traffic problem has time and again been blamed on an insufficient number of roads, traffic mismanagement, lack of operational traffic signals, and the disorderly movement of pedestrians. A development-obsessed Bangladesh decided to first tackle the problem of insufficient roads. I have watched as Dhaka changed before my eyes – the widening of roads, expansion of footpaths, building of flyovers, overpasses, underpasses, expressways – all in a bid to solve the traffic problem. Yet, the traffic situation seems to be getting progressively worse.

So, clearly, trying to make up for insufficient roads with more roads is not the answer to our traffic problem. This is true for other megacities as well. Why else is a 50-lane highway in China regularly plagued by gridlock?

Economists describe this phenomenon as induced demand. The more roads you build, the more cars there will be to fill them up. I am no expert, but the numbers don't lie: Despite all the new flyovers and expressways, Dhaka's traffic is so bad that the average speed has steadily slowed down over the years, according to one World Bank report. In the 10 years until 2018, the average traffic speed in Dhaka dropped from 21 kilometres per hour (kmph) to 7 kmph. And by 2035, the speed might drop to 4 kmph, which is slower than the walking speed, the WB report said.

Back in 2009, two economists, Matthew Turner of the University of Toronto and Gilles Duranton of the University of Pennsylvania, compared the building of new roads and highways in different US cities and the total number of miles driven in those cities between 1980 and 2000. What they found was described as a one-to-one relationship. If a city increased its road capacity by 10 percent between 1980 and 1990, then the amount of driving in said city went up by 10 percent. According to their paper, "The Fundamental Law of Road Congestion: Evidence from US cities", new roads end up creating new drivers, in essence maintaining the status quo of traffic jams.

The truth is, the easier we make it for people to move around in their cars, the more drivers will show up. Now, one may argue that heavily investing in public transit will solve the issue. But cases in other megacities have shown that while some opt for mass transit, more cars inevitably fill up the roads.

What happens if a road is removed from the equation, then? Well, in Paris, where the policy has been heavily geared towards reducing or downsizing freeways, the traffic has not gotten worse – it has remained the same and has readjusted.

So, what exactly is the solution?

Dhaka's traffic problem was not born out of just one issue, and there is no one answer, either. Experts have recommended discouraging the use of cars, increasing taxation on the ownership of multiple cars, mandating school buses – especially for English medium schools –, investing in public transit, introducing bicycle lanes, and lastly, not building more roads.

The existing roads should introduce more and more bicycle lanes, encouraging people to opt for other modes of transport while simultaneously discouraging car use. Adding to that, big cities such as Dhaka, Chattogram, Khulna, and Sylhet should think about introducing both parking and congestion pricing. It should be ensured that if someone is parking illegally during rush hours, they have to pay a hefty fine. As for congestion pricing, it is a tested tool to tackle traffic congestion that works by charging people during rush hour. One way to do this would be to introduce a kiosk or toll plaza at choking points to charge people using private cars during rush hours, unless they are in a medical emergency. Moreover, there should be dedicated lanes for ambulances and emergency vehicles so that they always have access to free roads.

In a city starved for public spaces, existing roads can serve the purpose of community spaces. This has been done in many neighbourhoods abroad, so why not for us? During weekends, the main thoroughfares can be used to host fairs or garage sales, hence encouraging more community participation.

Added to that, more and more investment in public transit – the Metro Rail and a fully functional bus service which is women-friendly – can change how we commute altogether. If people are aware that taking their cars out for a spin means more trouble, it is more likely they will try to avoid using their cars for everything. People need to know that there are other modes of reliable transport that are easily available. This in turn will reduce overall car use, hence bringing down both air and noise pollution. At the same time, the city needs to ensure that pedestrians can walk freely without their safety being compromised.

All in all, if we do not find a way to disincentivise the overuse of cars, we may never get out of this gridlock.

Abida Rahman Chowdhury is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star with interests in wildlife and biodiversity conservation.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments