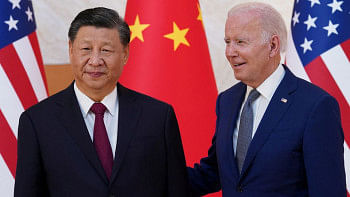

What could be behind Yellen's dovish gesture in Beijing?

Deng Xiaoping, a geopolitical genius and the architect of China's rise in the 1980s, once said, "The Middle East has oil. China has rare earth metals." Beijing has just reminded the world what that means in geopolitics by imposing export restrictions on germanium and gallium effective from August 1, sending shockwaves all over. Germanium is essential for high-speed computer chips, plastics, military applications such as night-vision devices, and satellite imagery sensors. Gallium is a crucial material for radio frequency chips for mobile phones, satellite communication, and other semiconductors. Rare earth elements, including these two, are indispensable for today's high-end economies and advanced military machinery. Any supply shortage may seriously jeopardise the production of electric vehicles, missiles, fighter jets, and super-fast AI chips.

Beijing holds 40 percent of the global rare earth reserve, but produces 70 percent of the raw supply. In the technically complex and environmentally hazardous downstream processing, it has near total control – 90 percent. With over 94 and 83 percent grip on germanium and gallium, respectively, the recent restriction is only a warning shot, and stricter regulations may follow, as The Wall Street Journal puts it. This is understandably a retaliatory measure in response to the sanctions Washington and its allies imposed on their technological, economic, and strategic rival – Chin, an emerging and assertive power.

Let's revisit the recent events that led Beijing to take a path of confrontation.

It began in 2018 with the Trump administration banning US agencies from using any systems, equipment, and services from Huawei, a Chinese telecommunications giant. It also cajoled the allies into dropping Huawei from their 5G networks. In July 2020, it sanctioned specific Chinese officials and their immediate families for gross human rights violations in Xinjiang.

In August 2020, Washington imposed sanctions on Hong Kong's Chief Executive Carrie Lam and 10 other officials for "undermining its autonomy and restricting the freedom of expression of the citizens." It extended the sanctions to 14 vice-chairpersons of China's National People's Congress in December.

In November of the same year, Trump prohibited all US institutional and retail investors from investing in or buying from Chinese companies that the Department of Defense listed as "Communist Chinese military companies."

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 triggered further sanctions against several businesses in China, such as Sinno Electronic for supplying Russian military networks, and most recently against Spacety China for providing satellite imagery to the Wagner Group. The Biden administration doubled the sanctions in October 2022, cutting China off from semiconductor chips made worldwide with US equipment.

In December, Washington imposed further sanctions on Chinese nationals and 10 entities in response to human rights abuses connected to "illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing."

In January 2023, the Netherlands' ASML stopped sales of crucial equipment to China's chipmakers under pressure from the US. Washington proposed to withhold even more Dutch equipment from specific Chinese fabrication plants.

Beijing's first formal retaliatory measure came in February this year, when it added Lockheed Martin Corporation and Raytheon Missiles & Defense to its Unreliable Entity List. Geopolitical changes and increasingly restrictive measures from Washington and its allies since 2018 have led Beijing to develop its own sanction policy tools on a priority basis. Before that, Chinese actions appeared more like expressions of displeasure.

Beijing, the emerging power, will naturally gain from a peaceful relationship with Washington. But that path won't be easy for Washington to follow for fear of losing control. However, the alternative way of conflict is more destructive, and there will be no winners – a message China wants Yellen to convey to Washington.

In 2009, China responded to then French President Nicolas Sarkozy's planned meeting with Dalai Lama only by cancelling its annual summit with the EU. Since it has taken active steps to control rare earth materials export, has it decided to deal with Washington's sanctions head-on? If so, what might be its ramifications for the ongoing geopolitical rivalry?

Weaponising control over rare earth materials may strengthen China's geopolitical position and increase its leverage over other countries. By manipulating the supply, China could exert pressure on nations heavily reliant on these minerals, using them as bargaining chips in negotiations or diplomatic disputes.

This is, however, unlikely to change the balance of power in international relations or any shifts in alliances and geopolitical strategies. Countries would reduce their dependence on China by fostering domestic production, exploring alternative sources, and strengthening international cooperation. But that may be a challenge.

One thing is certain: the sanctions war will only intensify as China has threatened more retaliatory measures against US export controls unless Washington follows a more reconciliatory path, which Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen appears to have shown. She told Chinese Premier Li Qiang that the US wanted healthy economic competition, not a "winner-take-all" fight, with China. Just before her, Secretary of State Antony Blinken flew to Beijing and discussed Taiwan and Ukraine without consensus. Blinken proposed direct communication between the two militaries, but received no positive response. A day after Blinken's meeting with Xi, Biden called the president a dictator, pouring cold water on any possibility of warming up on the other side.

Beijing, the emerging power, will naturally gain from a peaceful relationship with Washington. But that path won't be easy for Washington to follow for fear of losing control. However, the alternative way of conflict is more destructive, and there will be no winners – a message China wants Yellen to convey to Washington.

Is Yellen's dovish tone a genuine gesture following China's latest restrictions, or is she only the "good cop" in this strategic negotiation game? A "From Washington with Love" message just seems way too friendly.

Dr Sayeed Ahmed is a consulting engineer and the CEO of Bayside Analytix, a technology-focused strategy and management consulting organisation.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments