What future will young workers work for?

Lured by the promise of opportunities, the young and jobless flock to Dhaka. Yet, a decade of touted development, with boasts of mega projects and GDP, has fallen short for this country's most promising generation. Beyond the 2.2 million graduates, a vast number of school and college graduates from across the country languish in unemployment. Many dropouts seek refuge in the informal economy, while the rural economy itself shrinks. This exodus drives young people from rural areas to become Dhaka's hawkers, tailors, domestic helps, security guards, bus conductors, and the like. And thousands find their way into the ready-made garment sector.

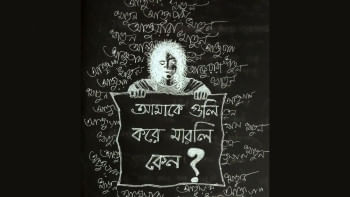

The tragic reality is that we've utterly failed to incorporate these young workers into our economic and political discourse. No mechanism exists to amplify their voices. Yes, they're allocated a share in the national budget, their employment woes are discussed, and they're granted some form of right to unionise. But for these individuals who are battling for a mere living wage, politics, the economy, and fundamental rights are beyond reach.

Over the past decade, many of the institutions in this country have been destroyed. The structures that ensure accountability have been weakened. Every path for young people to participate in politics has been made difficult. The entire economic structure is oppressive. The environment for creating even the minimum political process for workers to demand their basic rights has been destroyed.

Their very right to vote has been effectively denied for the past 15 years. Excluded from the regular political process, these young workers have no platform to articulate their financial struggles. Their economic lives are held captive in exploitative structures, with no clear path to improvement outside of committing to long-term, arduous organisational or political processes.

The garment sector is the most powerful in Bangladesh. Millions of 18- to 30-year-old men and women make up the driving force of this industry. Naturally, it held immense potential for these workers to blossom into a collective force, organising and advocating for their rights in the workplace and beyond. Here, they could have risen to become a vital voice in the nation's political arena, championing not just fair wages but also affordable necessities like food, utilities, safe transport, and national healthcare—issues that are central to their lives and livelihoods.

Tragically, the RMG industry systematically suppresses its workers' most basic rights from their first day. Unionisation and effective labour organisations are stifled by a combined effort of factory owners and the government. Denied even a platform to air their minor grievances, these young garment workers remain silenced, let alone being empowered to fight for broader rights.

In Western democracies, labour unions played a crucial role in shaping the political landscape. They fought for workers' rights, improved working conditions, and ultimately contributed to the development of strong, representative governments. Why isn't this the case for Bangladesh?

Factories in Bangladesh are not isolated entities. They exist within a broader political context marked by a culture of suppression and a decline in democratic values. Any attempt by workers to organise has been met with swift retribution from the state, law enforcement, and factory owners. These young RMG workers, despite their vast manual labour force, remain some of the most economically vulnerable and financially unprotected segments of the Bangladeshi population. Instead of harnessing their potential as a progressive force for economic reform and challenging the stark wealth inequality in Bangladesh, they have been reduced to tools for repression.

The Bangladesh labour laws clearly provide for the formation of trade unions, but the administration itself actively hinders this right. The legal requirement for a union is a 30-percent membership within a specific factory, and a list of potential members must be submitted to the labour office. However, upon receiving the list, the labour office promptly relays it to the factory owner. This information allows management to easily target those on the list for dismissal. Once fired, finding work in another factory becomes nearly impossible due to the stigma associated with attempting to unionise. Furthermore, government officials frequently demand substantial bribes when workers file applications for union registration. This pattern suggests a deliberate effort by the government to stifle worker organisation at its inception. This undemocratic practice has taken its root within Bangladesh's administrative culture, and until we put this structure on trial, the plight of these young people will remain unchanged.

In addition to these administrative barriers, being one of the most poverty-stricken and economically vulnerable classes of people has capped workers' ability to become "vocal." The factory takes up almost all of their daily lives. A worker has to work at least 10 hours to manage the minimum cost of living. And a female worker has to spend even more of her time cooking and doing other household work. How will these workers get the time to hold meetings and rallies for their demands, get involved in politics, and form unions?

Despite all of these, there are still workers' movements in the garment sector. But the consequences of these movements are often dire. For these spontaneous movements, workers are arrested, harassed, and attacked by the police or by factory management. They are accused of stealing factory goods, damaging "public property," and have cases filed against them. Threats and intimidation from influential people of the ruling party continue to hound workers. As a result, many young workers in the sector decide that it is better to keep quiet.

The image of youth that we see on the billboards of digital Bangladesh does not represent the faces, skin colours, or attire of the true majority of the youth of this country. The majority of the youth in this country work in factories, operate machines, do odd jobs, drive rickshaws or auto rickshaws, or try to sell products on the sidewalks. Unfortunately, there is constant police repression in every one of these sectors. Extortion by the police or by linemen when sitting on the sidewalk, being beaten and having fines imposed when taking a rickshaw out on the road—these are the things the majority of urban youth experience every day.

In the garment sector, there are at least some precedents of collective youth organisations. Even though they cannot form unions formally, young RMG workers at least have the opportunity to exchange thoughts, feelings, or anger because they share a workspace and live in similar neighbourhoods. But the youth in the informal economy are so disconnected and so unprotected that there isn't any possibility in sight for them to have a platform through which to talk about their working conditions, let alone organise and form unions. In an environment where even formal institutions fail, there is no way for these youth—who are scattered across different sectors of the informal economy—to hold "dialogue" with the administration and demand protection for their livelihood.

Over the past decade, many of the institutions in this country have been destroyed. The structures that ensure accountability have been weakened. Every path for young people to participate in politics has been made difficult. The entire economic structure is oppressive. The environment for creating even the minimum political process for workers to demand their basic rights has been destroyed. There's no functional platform for negotiation with the government or the state machinery. Even when elections bring a change of authority, the plight of the working youth remains unaddressed.

There has been a lot of excitement about the 40 million first-time voters. There was hope that the youth of this country would be able to vote properly after 15 years. There seemed to be a positive environment to discuss human rights, the right to vote, and freedom of expression. But just like the possibility of a participatory election, this dream has largely died out. It is difficult to say what kind of politics await the youth of Bangladesh in the coming years. However, the most unfortunate thing is that even amid all this election hullabaloo, the majority of the youth in this country—the working class—has always remained neglected.

To include working-class youth in political and economic decisions, it is necessary to make it easier for them to organise, make the institutions of democratic practice effective, increase government initiative and investment in creating employment, and create a strong culture of accountability against all forms of institutional repression. It is not possible to bring fundamental change in Bangladesh's politics if this young working-class population remains excluded.

Translated from Bangla by Naimul Alam Alvi

Maha Mirza is a researcher, and part-time lecturer at the Department of Economics of Jahangirnagar University.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments