What makes great research?

The ill state of research at Bangladeshi universities is well-known. Why is there such a reluctance to patronise research work in the country's higher education institutions? In the fourth part of a series that focuses on some of the most foundational and important issues of higher education in Bangladesh, three academic professionals delve in to decipher the holdbacks in our university research. The Daily Star welcomes and encourages any and all thoughts, ideas, and recommendations regarding these issues from our respected readers.

Research is a mindset, as much as it warrants a discipline-specific set of skills to carry it out. Fostering that mindset requires collaboration of the government, public and private sectors, university administration, industry, professors, and students, among other stakeholders. Starting with a why or a how, research can be qualitative or quantitative, or both, providing us with sharper lenses on the world around us or new solutions to our problems. Because the capacity to create new knowledge provides nations with an edge to prosper faster than their peers, robust investment in research and development (R&D) is now considered essential. In 2021, the total global R&D spending reached $2.3 trillion.

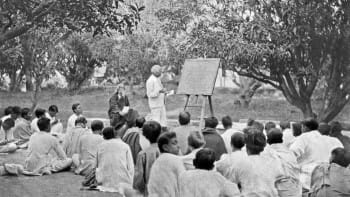

The epicentre of research is, of course, the university. A research university is a powerful engine for change and transformation – a shaper of knowledge production that in turn drives economic and intellectual growth, modernisation, and the development of soft power. China's strategic investment in its universities is a good case in point. The transformation of Chinese universities from resource-deficient institutions during the Cultural Revolution to dynamic centres of research and innovation today is a classic case of intellectual capital being at the heart of a country's national mission. In 2017, a record nine Chinese universities were ranked among the world's top 100 universities for the first time.

But what is a research university? Simply put, it is an institution of higher learning in which original research and scholarship drive its mission and vision, as well as its pedagogical orientation and curricular framing. Professors at a research university spend a significant amount of their professional time conducting original research, rather than simply teaching knowledge produced by others. In the United States, a full-time faculty member's professional time is typically divided into 40 percent teaching, 40 percent research, and 20 percent service.

Yet, not all universities are research institutions. Consider the history of research universities in the US. With about 4,000 colleges and universities in the US, only 2.5 percent of them are research universities. The Association of American Universities (AAU) – founded in 1900 during what was referred to as the US' "Academic Revolution" – has only 65 members. Most of the US' research activities take place in this small number of member institutions. The Academic Revolution of the late 19th and early 20th centuries catalysed a sea change in the nature of US universities, as research became a core mission of higher learning, significantly transforming pedagogical philosophy and curricula, and gradually cementing the US' emergence as a global power. In FY2021, the total R&D spending across US universities reached $89.9 billion, with Johns Hopkins University claiming the top spot with $3.181 billion.

What is the status of research in Bangladeshi universities? According to one survey, about 125 universities across Bangladesh spent about Tk 153 crore in 2020, or approximately 0.3 percent of GDP. This paltry amount shows how research is imagined in the national mission. I identify three key interrelated problems, by no means exhaustive, that result in a poor research culture in Bangladesh.

First, our universities are predominantly undergraduate teaching universities with a strict UGC-mandated curriculum focused on building basic student competencies. Our teachers teach a course, administer tests, and grade students. The academic space to cultivate critical thinking and a research mindset among students cannot be built in such a course trajectory, often plagued by a routinised syllabus (sometimes with an outdated textbook or no textbook at all) with a predictable set of deliverables. When professors are primarily tasked with lecturing large undergraduate classes with very little room for self-scrutiny and intellectual challenge from students, they remain unmotivated to undertake any research projects that complement their teaching or broaden their knowledge horizon. Without robust, flexible, and multidisciplinary graduate programmes, teaching universities are unlikely to incentivise research.

Bangladesh has succeeded in expanding access to primary education, achieving near universal net primary enrolment. But higher education in this country still awaits a creative framing in sync with the ground realities and aspirations. Fifty-two years after independence, this sector is yet to transition to a new type of research-driven knowledge economy – one in which students are empowered to develop agency, curiosity, and intellectual capital to compete in and adapt to an interconnected world.

Second, the laissez-faire nature of faculty promotion, exacerbated by what I call "academic cronyism" – that is, if you butter up your supervisor or the department's power-wielder, you will be promoted despite your lack of research productivity – creates an unholy environment of "favour-peddling." In such a condition, an assistant professor is less interested in original and labour-intensive research than resorting to sycophantic loyalty to the programme chair who would return the favour. In a reputable university in any developed country, no faculty member can expect to be tenured without a significant body of original publications, reviewed first by colleagues at the department and then by the university senate before the entire application package reaches the provost's office. This creates faculty accountability in establishing credentials.

Third, Bangladesh has succeeded in expanding access to primary education, achieving near universal net primary enrolment. But higher education in this country still awaits a creative framing in sync with the ground realities and aspirations. Fifty-two years after independence, this sector is yet to transition to a new type of research-driven knowledge economy – one in which students are empowered to develop agency, curiosity, and intellectual capital to compete in and adapt to an interconnected world.

Transitioning to such a state of higher education will require robust investments in "research infrastructures," such as technologies of research, recordkeeping, archives, laboratories, grant support, research investment, research-focused curricular reform (strengthening teaching at the same time), faculty hiring and promoting protocols, academia-industry-government collaboration, a local-global peer-reviewed publication industry, global research collaboration and networking, and, most importantly, a dynamic culture of knowledge production.

No one would disagree that the 21st century belongs to those countries that produce ideas and knowledge. There is a caveat though. The production of knowledge as a culture can't simply be instituted through research universities. The joy of producing knowledge must be an integral part of doing research. I am reminded of what Stephen Hawking memorably said, "No one undertakes research in physics with the intention of winning a prize. It is the joy of discovering something no one knew before."

Dr Adnan Zillur Morshed is an architect, architectural historian, urbanist, and professor. He teaches at the Catholic University of America in Washington, DC, and serves as executive director of the Centre for Inclusive Architecture and Urbanism at Brac University.

***

I met Bhupendra Nath Dev on the campus of the State University of New York at Albany in 1982. He was working on his PhD in physics; I went there to do a Masters in Russian literature. He had graduated from Rajshahi University. I'd ask him questions about physics and he'd happily answer them, but often via detours into literary works, loving references to Tagore, and naming physicists that I had never heard of. But I asked why, despite his profound love of literature, he rarely asked me about literature. He said when he was growing up, his father would become irritated and slap him behind his head for asking too many questions! So he stopped asking questions. Bhupen left Bangladesh with his family after 1971 and settled in Calcutta.

With an astounding amount of research and publications, Bhupen is now one of the most renowned physicists in his area around the world, and if he were to get a Nobel Prize any day now, I wouldn't be surprised. Despite his father's dislike of answering questions, Bhupen somehow kept his curiosity alive and learnt to do original research and find the answers to his questions. However, what makes me wonder is how many hundreds and thousands of Bhupens have stopped asking questions, how many brilliant scientists, scholars, and inventors we have lost because of our general practice of discouraging curiosity and disliking questions.

Research refers to systematic investigation of phenomena through scientific methods to generate new knowledge, insights, and solutions. It involves collecting, analysing, and interpreting data in an unbiased manner to test hypotheses, answer questions, and find solutions.

Developing research potential in Bangladesh has become imperative in order for us to move forward as a nation, keep our economy growing, develop an educated citizenry, and, above all, create a "smart" Bangladesh – as our nation's leader Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has mandated. Investing in education adequately will drive the economic and social growth of our nation. In order for this to happen, sustained effort and collaboration from all corners, including the government, the universities, and the private sector, are required. The mandate is there; the proper authorities need to implement it now.

Bhupen's story tells us a lot about why research in Bangladesh is in such an abysmal state. In a culture where critical inquiry is not only discouraged but even punished – either physically or emotionally – research is the last thing to get the chance to flourish as a system of thinking. In a culture where we are taught to believe that answers to all questions have already been given in some form of a code, critical thinking can have little, if any, value. Doing research is difficult in this environment, and we need to change that.

High quality research brings enormous benefits for national growth and for the standard of life. Medical research, for example, has eliminated diseases and ameliorated sicknesses that for millennia had made people live no longer than 20-30 years on average! Invention of new technologies, products, and services stimulates economic growth, creates high quality jobs, makes our manual tasks easier, creates better quality living, protects our environment, and more.

Recognising the fact that knowledge is important for changing human society is critical. That'd be the first step for us. National leaders have to allocate resources for research. That's next. We have to recognise the fact that allocating approximately two percent of our national GDP (even the other South Asian nations invest a minimum of 4.5 percent) for education is NOT going to help us catch up to the rest of the world. We must understand that the lack of funding leads to limited access to technology, few research networks and collaborations, inadequate infrastructure, virtually non-existent research institutions, almost total absence of institutional support, and obviously the most damaging one – the huge brain drain from our nation. These issues must be resolved.

Developing research potential in Bangladesh has become imperative in order for us to move forward as a nation, keep our economy growing, develop an educated citizenry, and, above all, create a "smart" Bangladesh – as our nation's leader Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has mandated. Investing in education adequately will drive the economic and social growth of our nation. In order for this to happen, sustained effort and collaboration from all corners, including the government, the universities, and the private sector, are required. The mandate is there; the proper authorities need to implement it now.

Dr Halimur R Khan is a university professor and can be reached at [email protected].

***

Knowledge, today, is the new currency. Altbach and Salmi (2011) contend that "knowledge generation has replaced ownership of capital assets and labour productivity as the source of growth and prosperity… This realisation is so pervasive that nations are scrambling to create institutions and organisations that would facilitate the process of knowledge creation."

In this feverish scramble, where does Bangladesh stand? Willem van Schendel (2019) contends that Bangladesh lacks scholarly visibility, with a "relatively disjointed and poorly institutionalised field of knowledge production."

Why are we so far behind? Why is our research disjointed? Are we even capable of conducting good research (barring the exceptional few)? These questions provoke another query: what is good/great research?

Great research relies on the scientific method, extends knowledge frontiers, reflects the quality of a nation's brain pool, and even locates nations on a "smartness" scale, reflecting their capacity to innovate and thrive. Smart nations continually examine interesting-unanswered-useful questions through research, whether applied or basic. Applied research is conducted to find solutions to a particular problem (low attendance in a particular school, for instance). Basic research addresses fundamental questions and at a more general level (such as low school attendance across the nation), extending the structure of knowledge and contributing to theoretical development.

Once a problem or gap is identified, a method of inquiry is adopted to obtain robust, relevant, and reproducible results. But choosing a method poses challenges, especially in the social sciences, arising from ontological and epistemological assumptions about the reality being investigated. The subjective/interpretive assumption of reality is of a softer and spiritual/transcendental quality; an objective/positivist view is of the world being hard, real, and transmissible. The constructivist pursues qualitative/interpretive methods and generates hypotheses; the positivist seeks hard sensory data to test hypotheses. The debate on the nature of reality is contentious and ongoing. Hence, some researchers combine both.

The subpar quality of knowledge our institutions usually generate today, reflected in global standings, has only increased our dependence on foreign knowledge sources with little local relevance. Such dependence usually translates into exploitative relationships. The greatest harm to our research endeavours may come from consultancy and non-transparent research projects, distributed surreptitiously in a sycophantic culture, that come with predetermined findings to serve a small coterie of beneficiaries. That death knell will incapacitate Bangladesh for generations.

Beyond methods and creative analytics, great research, as I have indicated earlier (in "Public universities and research: In 2022 and beyond") is "immersed in rigorous and challenging work, passionately pursuing new realms of knowledge, often in a process involving teacher and student, collaborating institutions, and global partnerships. The goal is problem-solving and discovery, reflected partly in publications that are recognised, frequently cited, and acknowledged for their impact. Such research [builds] on top-class graduate programmes and meritorious graduate students led by creative, dedicated, and research-capable faculty mentors. When teaching is research-led, the learning of both teacher and student is greatly enhanced with deep [positive consequences]." Good research flourishes in a culture devoted to curiosity, teamwork, and a spirit of discovery.

Ultimately, top-flight research seeks to advance the human condition. According to Hoover (1976, Pg 7), "Knowledge is socially powerful only if it… can be put to use." It follows ethical guidelines, solves problems, enhances our understanding of a novel or interesting research question, extends the frontiers of knowledge, decries plagiarism, and is recognised for its wide-ranging influence.

Great research also thrives in dynamic ecosystems, nurturing a culture of inquiry and collegiality, dedicated to an ethical investigation of the truth, and flourishing in a network of stakeholders – the government, industry, private funds, media entities, rating agencies, publishing houses, markets (educated readers) for research products, and platforms to share emerging ideas (conferences, seminars, etc) – each contributing to and benefiting from knowledge. "The intent is to create a wide set of producers, consumers, partners, sponsors, and support systems – in essence, a market – for research to flourish with many positive externalities."

For research to blossom in Bangladesh, it will require strong political support, sustained financial commitment, leadership and autonomy in the university, rewards and incentives, and a steady stream of high quality students who seek a life dedicated to problem-solving and discovery.

The subpar quality of knowledge our institutions usually generate today, reflected in global standings, has only increased our dependence on foreign knowledge sources with little local relevance. Such dependence usually translates into exploitative relationships (e.g. the Covid vaccine heist). The greatest harm to our research endeavours may come from consultancy and non-transparent research projects, distributed surreptitiously in a sycophantic culture, that come with predetermined findings to serve a small coterie of beneficiaries. That death knell will incapacitate Bangladesh for generations.

Dr Syed Saad Andaleeb is distinguished professor emeritus at Pennsylvania State University in the US, former faculty member of the IBA, Dhaka University, and former vice-chancellor of Brac University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments