Why is it taking so long to stabilise the economy?

Bangladesh's economy showed remarkable signs of swift recovery from the adverse effects of Covid-19, but this progress was cut short by the advent of serious macroeconomic imbalances in April 2022. These imbalances are reflected in high inflation, depleting foreign exchange reserves, pressure on the exchange rate, shrinking capital inflows, and pressure on the budget. To address the stabilisation issues, the government entered a four-year programme with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Implementation of the second year of the programme is currently underway.

While the government's intentions to address the macroeconomic stabilisation challenges are laudable, the results so far fall short of what is necessary. Inflation remains high, the availability of foreign exchange is severely constrained, GDP growth is on a downward trend, investment rates are down, and export growth is much below the long-term trend. Shortage of foreign exchange and the associated import cutbacks are constraining the recovery of GDP growth, private investment, and exports.

My research, documented in a new book titled Bangladesh Stabilizing The Macroeconomy, suggests that the reason for the slow progress in macroeconomic stabilisation is the inadequate implementation of required reforms. At the initial stage, the main policy response was to manage the balance of payments with import controls and use of forex reserves, and to control domestic inflation through budgetary subsidies on oil, gas, electricity, and fertiliser. An effort was also made to protect GDP growth and investments through a strong control over interest rates, by increasing fiscal deficits, and through liberal use of Bangladesh Bank financing of fiscal deficits.

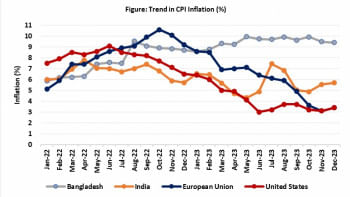

These policies, instead of helping the stabilisation agenda, further worsened the imbalances. There was an unsustainable run-on forex reserve that put pressure on the exchange rate, foreign capital flows fell, and the inflation rate accelerated approaching nearly 10 percent. Growing budgetary subsidies lowered spending on core social services and put pressure on fiscal deficits. To stem the slide of the exchange rate, the government further tightened imports, which declined by 27 percent from the FY2022 level, adversely affecting GDP growth, investment, and exports.

What went wrong? The macroeconomic imbalances have emerged from three sources: inflationary pressure; the balance of payments pressure; and fiscal pressure. Addressing these issues requires the use of at least three policy instruments that best relate to each of these areas: monetary policy to ease the inflationary pressure; exchange rate policy to ease the balance of payments pressure; and tax or expenditure policy measures to ease the budgetary pressure. Their combined use as a coordinated set of policy actions can help avoid the bluntness of any single instrument and reinforce the effectiveness of each of the policy reforms.

Regarding balance of payments management, excessive reliance on import controls is inconsistent with GDP growth acceleration. While selective import controls can play a short-term emergency adjustment role, resorting to import controls can cause serious supply disruptions, discourage domestic and foreign private investments, hurt exports, and lower GDP growth. The only sustainable way to manage the balance of payments pressure is to focus on the supply side to increase exports and to use demand-side instruments to lower demand for imports.

A critical determinant of exports is the incentive policy regime. Investors will produce and export only if the profitability from exports exceeds the profitability from domestic production. Two key determinants of export profitability are the exchange rate and trade protection. An overvalued real exchange rate hurts exports and encourages production for the domestic market. Similarly, the higher the trade protection, the higher the incentives for domestic production and bias against exports.

Concerning the exchange rate management, a fundamental problem is that the exchange rate has been highly overvalued for an extended period of time, as reflected in the appreciation of the real effective exchange rate (REER) by an overwhelming 57 percent between FY2011 and FY2022. By failing to correct this overvaluation on a timely basis, Bangladesh exposed its currency to substantial depreciation between April 2022 and September 2023. Even so, the taka today is still appreciated by 40 percent in real terms over 2011.

More generally, a sustainable way of managing the balance of payments would be to let the exchange rate be market-determined. This should be complemented by trade policy reforms that lowers trade protection and the anti-export bias of trade policy. A flexible exchange rate along with lower trade protection will boost exports and remittances, thereby increasing forex supply. On the demand side, reduction in private spending through increase in interest rate combined with higher taxes and lower fiscal deficit will help reduce the demand for imports and avoid the exchange rate from over-shooting.

Regarding inflation management, research shows that globally as well as in Bangladesh the main source of inflationary pressure is excess liquidity in the system resulting from the pandemic-time stimulus packages. In Bangladesh, these were further intensified by the persistence of interest controls through the "6/9" interest rate policy, rising fiscal deficit, and liberal Bangladesh Bank financing of fiscal deficit. Thankfully, since September 2023, the 6/9 interest rate policy has been abandoned and the Bangladesh Bank has stopped financing the budget deficit. This is a welcome reform, which has already lowered the pressure on the exchange rate. Inflation reduction will take time and may require further increases in the interest rates. Most importantly, the budget deficit must be reduced to lower inflation. This has not yet happened owing to the inadequacy of fiscal reforms.

Concerning fiscal policy, the required policy approach is to cut the fiscal deficit by increasing revenues through meaningful tax reforms and by reforming the state-owned enterprises (SoEs). Every year, the government sets ambitious tax targets that are not met. As a result, the tax-GDP ratio is not only extremely low at less than eight percent of GDP, but also declining or stagnant. Meaningful tax reforms require addressing the substantial institutional constraints to help establish a modern tax system in the country. This would be much more effective than setting ambitious tax revenue targets through ad-hoc tax measures. Regarding SoE reforms, the government must recognise that it has invested heavily in these enterprises but the financial rate of return on this investment is exceptionally low due to corporate governance and pricing constraints. For example, the book value of total assets of non-financial SoEs was estimated at around 17 percent of GDP in FY2021. A 10-12 percent return on these assets should yield profits of 1.8-2 percent of GDP. In sharp contrast to this, actual profits were only about 0.6 percent of GDP. The case for corporate governance and pricing reforms of SOEs is obvious.

Dr Sadiq Ahmed is vice-chairman of the Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh (PRI). He can be reached at [email protected].

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments