Five ways to raise garment worker wages

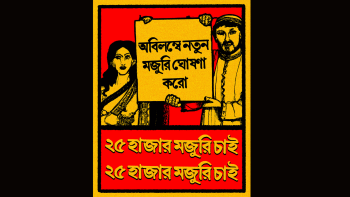

After many months of negotiations, the national minimum wage for garment workers in Bangladesh was formally announced last week—Tk 12,500 ($114). This has been met with mixed reactions. Unions and worker rights groups argue that the increase should have been greater, while factory owners justify the new wage by saying that it is a 50 percent hike.

I am not here to discuss the merits of either of these arguments. Instead, I want to explore how we can increase wages, focusing on five potential strategies and outlining the pros and cons.

The first way is through advocacy. This involves collaboration between labour unions, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and other stakeholders to promote policies that establish minimum wage standards, ensuring that workers receive compensation commensurate with their efforts. Governments can play a crucial role by implementing and enforcing such policies, creating a legal framework that protects the rights of workers and guarantees a living wage.

Advocacy efforts in Bangladesh have been part of the national dialogue centring wages for several decades. The pros of such an approach is that it is democratic and collaborative. It brings in many different voices and organisations, which can help spread the word.

There are no downsides to such efforts. However, it is debatable as to how much impact such work has had in Bangladesh, where the garment industry at times appears to be trapped in a cycle of low wages despite the best efforts of rights groups and unions.

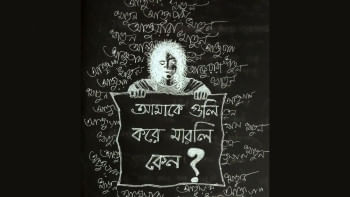

The second strategy involves promoting transparency and accountability in the fashion industry's supply chains. Many major brands and retailers source their products from factories with low-wage labour, often in developing countries. Through encouraging transparency in these supply chains, consumers can make informed choices that support companies committed to fair labour practices. Brands, in turn, can be held accountable for ensuring that workers throughout their supply chains are paid fair wages and provided with suitable working conditions.

Transparency can, indeed, help shine a light on supply chain issues. When consumers find out more about the people who make their clothing, they can urge their favourite fashion brands to support pushes for better wages for garment workers.

That said, transparency has its limitations. Initiatives such as "Who made my clothes?" have been around for many years. Have they made a difference to garment workers? Have the impacts of such efforts fed through to better wages? There is very little evidence to suggest this is the case. Perhaps Western consumers have become blase about such issues; maybe they are happy to purchase extremely cheap clothing while turning a blind eye to the social issues associated with it.

Option three is to improve factory efficiency so that any salary increment can then be more easily absorbed, making it possible to pay workers more. Look at the example of China, where salaries are higher than Bangladesh: it remains the top apparel producing and exporting country.

Improving operational efficiency involves taking a closer look at all aspects of a factory—including knitting, yarn cost, dyeing, weaving, printing, washing, dry processing, embroidery, accessories and embellishments. Above all, owners need to consider profit margins and think how broader savings can be made to help push a larger share of the budget to wages.

Elevating the skills of garment workers can lead to increased productivity and, consequently, higher wages. Investing in training programmes that enhance workers' capabilities not only benefits the individuals involved but also contributes to the overall competitiveness of the industry. Governments, businesses, and NGOs can collaborate to establish vocational training initiatives that empower workers with the skills needed for more specialised roles within the garment sector, leading to higher pay for skilled labour.

I am a big supporter of this approach. Rival countries such as China and Vietnam have increased wages by upping training and productivity and enabling workers to produce higher value added products.

There is no downside to this approach, and the push to improve skills in Bangladesh is a major theme within the industry. This will, however, take time, especially as Bangladesh has become somewhat typecast as a low-value, low-cost option among buyers. On this front, we need to change perceptions.

Finally, there is a legally binding option to increasing wages. Here, in a similar way to the Bangladesh Accord, we would create a platform for buyers, suppliers, NGOs, unions and rights groups to sign up to a programme for agreeing on minimum standards on purchasing practices. This would cover prices paid for orders with a target of funding better wages. There is already a successful, replicable model available, which is the RMG Sustainability Council (RSC).

With all these choices in our hands, what are we waiting for?

Mostafiz Uddin is the managing director of Denim Expert Limited. He is also the founder and CEO of Bangladesh Denim Expo and Bangladesh Apparel Exchange (BAE).

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments