Heatwaves, global warming, and the ethics of our cities

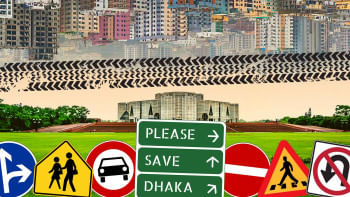

Recent heatwaves in cities across the world have stirred a lot of thinking about what to do with the "heat island effect." In layman's terms, the heat island is a localised thermal condition created by a city's built environment – in which we typically see a lot of concrete and asphalt surfaces, densely built houses, paved areas, absence of green spaces and waterbodies (relative to rural areas), carbon-emitting industrial activities and vehicles, and a lot of people and their daily work. The heat island reaches its peak during the night when the city's buildings and heat-absorbing surfaces emit heat they have accumulated during the day. The heat island's temperature is considerably higher than those of its surrounding areas. Dhaka has become a classic example of heat island effects, resulting in vast public health inequities. In their labour-intensive jobs that often expose them to the scorching sun, the urban poor suffer the most in a heat island like Dhaka.

Dhaka's recorded highest temperature this year so far, according to the Bangladesh Meteorological Department, was 40.5 degrees Celsius. The Dhaka North City Corporation has recently appointed a chief heat officer (CHO), a local government position that emerged in many cities of the world in the early 2020s. At a very basic level, the CHO develops strategies to alleviate the city's heat island effects.

The cumulative heat island effects of the world's cities have something to do with global warming and climate change. We often don't make this connection. It is important that we do, as there are robust policy implications. The world's aggregate urban areas cover only 3 percent of the planet's surface but they produce 80 percent of the world's GDP. Those who occupy this meagre 3 percent area consume 80 percent of world's energy. Because of their high carbon footprint and heat-producing activities, cities are responsible for most of the global warming and climate change-related vulnerabilities. Thus, paradoxically, if cities are the root cause of global warming, they are also an opportunity for its mitigation.

That means urban planners, architects, local government officials, policymakers, and regulatory bodies must see the city's heat island problem through the broader lens of global warming because both are the result of the same phenomenon at two different scales. That also means we must rethink how cities are planned, designed, and administered to combat the adverse effects of both the heat island problem and climate change.

This is counterintuitive because when we think of the effects of climate change, we usually conjure up haunting images of coastal areas, melting icebergs, deserts littered with animal carcasses, and drought-hit territories with burnt trees. We seldom think of the city as the cause of climate change. We rarely examine how the processes of urbanisation and climate-related vulnerabilities are deeply interconnected. Mitigating climate change problems, thus, requires a sustained and ethical engagement with the ways cities are developed.

Bangladesh has missed this policy focus so far. Here, the climate change conversation has been singularly dominated by the spectre of a "southern threat." That is, with ongoing global warming and the resultant sea-level rise, a significant landmass of Bangladesh's coastal south would disappear under water. And, a vast coastal population would lose their livelihood and become climate refugees, destabilising local and regional security. Al Gore's Oscar-winning documentary, An Inconvenient Truth (2006), helped popularise this view of Bangladesh among the global community concerned with climate change and its disastrous effects on such low-lying countries as Bangladesh and the Maldives.

The susceptibility of Bangladesh's southern seaboard to global climatic catastrophes could not be underestimated. But a monolithic emphasis on the southern threat, unfortunately, blurs the urgency of the country's more immediate environmental threats due to rapid, ecology-defying urbanisation. An immediate environmental menace with long-term climatic implications lurks at the geographic centre of the country because of the uncontrolled urban growth of Dhaka and its deleterious effects on the fragile land-water ecosystem that has historically sustained the capital and its surrounding regions. Dhaka's frenzied growth in all directions – devouring rivers, water bodies, and agricultural lands – is as serious an environmental threat as the coastal dangers posed by the sea-level rise.

urban planners, architects, local government officials, policymakers, and regulatory bodies must see the city's heat island problem through the broader lens of global warming because both are the result of the same phenomenon at two different scales. That also means we must rethink how cities are planned, designed, and administered to combat the adverse effects of both the heat island problem and climate change.

The capital's frenzied urban growth – along with its skyrocketing energy consumption – should alarm us about the urgent need to view cities as the frontier of climate change. Time has come to realise that with smart energy consumption, environment-friendly, and people-centric urban design, cities present the most potent weapon to combat climate-related environmental problems.

This brings us back to the basic question. How do we lower the city's temperature as a solution to the problems of both the heat island and global warming? The easy answer: regulate and reduce the city's heat-generating surfaces and activities without sacrificing its economic opportunities. There should be two sides to this task: a. design and planning resilience and b. innovative regulation.

Let's talk about design and planning resilience first. We should consider the city's green as a soft and low-investment-high-yield public health infrastructure. Just as we need vaccines to protect ourselves against the pandemic, we need green to survive well and remain healthy. Thus: Rewild the city. Strengthen the city's green lungs. Expand green spaces. Cover heat-producing pavements and building roofs with green canopies. Most authoritative research confirms that green helps mitigate air pollution, heat, and noise, and enhance public health and mental wellbeing.

Planning resilience today must include environment-friendly mobility options in the city. Thus: Create and promote an affordable mass transit network that serves most areas of the city, both creating a transit-oriented compact urban DNA and reducing the city's need to expand into neighbouring floodplains and agricultural lands to house the growing urban population. Reduce dependency on private cars. Less private cars on the street means less emission, less carbon, less heat, and less noise. Champion bicycling and walking as carbon-free commuting options. Invest in bike paths and footpaths to minimise the city's carbon emissions. Today, there is a growing movement in western metropolises to transform parts of vehicular road space into green space. This is how the rewilding of the city begins at a micro scale. If you visit New York or Washington today, you can't miss seeing how vehicular road space is shrinking in favour of green and pedestrian space. A fight against global warming can begin in one's neighbourhood.

Let's talk about the seemingly oxymoronic concept of "innovative regulation." Innovation implies free thinking, whereas regulation suggests control. So, how does innovative regulation work? In a free society, one can't control how an architect designs a building. But let's pose this question. Should an architect design a tall building with an all-glass west facade? Under a fierce tropical sun, a building with a glass west façade literally becomes an oven in the afternoon. One can, of course, use up a lot of energy to cool the building by deploying an expensive air-conditioning system, which then becomes a key contributor to the heat island.

This is a case of environmental injustice, one in which a selfish building releases a lot of heat to the city, disregarding the city's public health. How do we then create a regulatory framework that ethically encourages the architect to design a building with a lot of natural shading and ventilation so that it doesn't need to depend on the wasteful, energy-guzzling artificial climate control of the building? This is both a design question and a moral quandary. Both should be part of necessary policy debates on environmental sustainability and urban equity. Innovative regulation may strengthen the ethical foundation of and incentivise environment-friendly architecture and cities.

To create a culture of innovative regulation in cities, the government may consider creating an autonomous executive agency to oversee environmental sustainability matters in Bangladesh. A good example could be the US government's Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), created in 1970 during the heyday of environmental movements in America. The US president appoints, and the Senate approves, the EPA administrator. In consultation with state, tribal, and local governments, the EPA sets national guidelines for the environmental well-being of the country. Empowered to create environmental regulations, such an autonomous executive agency can promote environmental research, education, awareness, and innovative regulation. If the mayor of the Dhaka South City Corporation applied to cut the trees on Sat Masjid Road, an autonomous environmental protection agency would have denied him the permission. The world's liveable metropolises are reducing the road width to discourage automobile dependency and encourage both pedestrianism and greening. We are doing the opposite in Dhaka.

When development takes precedence over nature's balance, when human activities radically alter a place's elemental geography, their environmental consequences are bound to be calamitous. Since Bangladesh's future is urban, the most effective place to ensure the country's ecological well-being is its cities.

Adnan Zillur Morshed is an architect, architectural historian, urbanist, and professor. He teaches at the Catholic University of America in Washington, DC, and serves as executive director of the Centre for Inclusive Architecture and Urbanism at BRAC University. His most recent book is Dhaka Delirium. [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments