Birth centenary of Tajuddin Ahmad: The unsung leader of our Liberation War

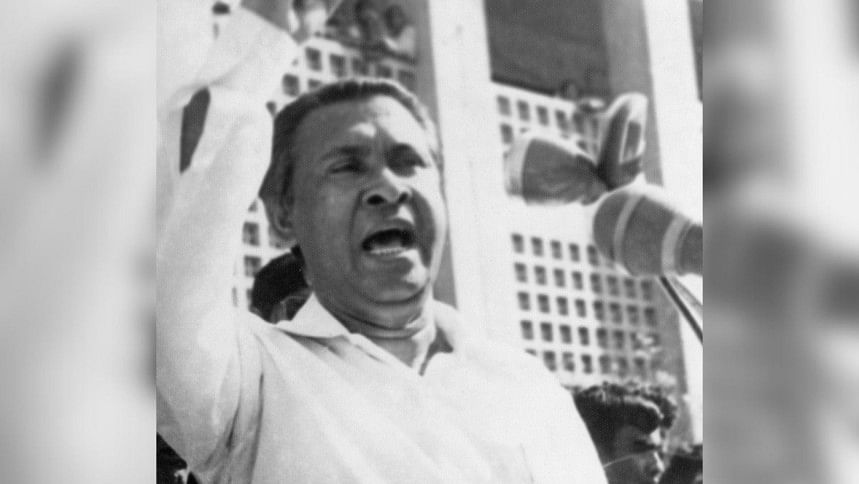

Tajuddin Ahmad was an exceptional leader on many counts. His commitment for the downtrodden, his personal values of austerity, his self-discipline, his ability to focus on the task at hand without being distracted, his unselfish nature, and his determination and fearlessness together made him a rare leader anywhere in the world, especially in Bangladesh where moral values of politicians and their capacity to put the country above their personal interests is always a rare trait.

It is sad that an occasion like the birth centenary of a man like Tajuddin Ahmad is not being celebrated at the national level or by many more civic, intellectual and academic bodies. This is evidence of our lack of respect for history, dismal record of honouring our heroes, and the intellectual bankruptcy and, more sadly, intellectual cowardice in which we now live.

The decision by Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman on March 25, 1971 to stay back and court arrest by the Pakistanis and that by Tajuddin to venture into the totally uncertain world of armed struggle to gain our freedom marks for the man—and of course for the nation—the most significant turning point in our history. A lot has been written about Sheikh Mujib's decision to stay back. Many views have been critical and some not so. Arguments exist on both sides. My purpose today is not to discuss the merit or demerit of Bangabandhu's decision but what impact it had on Tajuddin's life.

From being Bangabandhu's second in command, the task for Tajuddin now was to lead the nation. And he did so with stupendous courage, determination, patriotism and exemplary leadership.

When we follow his journey through those nine crucial months and focus on how he evolved from a successful party organiser to the de facto commander-in-chief of our independence struggle, we realise the versatility and strength of his inner potential. He rose to the occasion, expanded his capabilities of thought and action, widened his knowledge and vision, and, most importantly, established his leadership to face the various and unprecedented challenges and served the cause of our independence as no one else. No politician of the era, let alone Tajuddin himself, was remotely prepared to lead in an armed struggle. Yet, with confidence, dignity, strategic instincts, and unmatched integrity, he led the nation in spite of ever new impediments that emerged most damagingly, from within his own party.

To put it simply, his task now was to mobilise the nation to fight and convince the world to help.

Imagine this man, along with his associate Barrister Amirul Islam, hiding in Old Dhaka for the first two days, slipping out of the city disguised as a day labourer, criss-crossing the countryside mostly walking and sometimes on boat, all the while deeply contemplating how to organise the armed struggle against Pakistan.

The first glimpse that we get of his state of mind is when he reached the border and said he did not want to enter India as a "refugee" seeking shelter but as the "representative of an independent country" seeking assistance. According to Amirul Islam's account, they waited for a long time to hear from the Indian side (Indian border forces had to consult their superiors) and at one point, being extremely tired, fell asleep on a culvert. The man who was destined to become prime minister of the Liberation War government within a few days thought nothing of sleeping on a culvert. That was how his revolutionary mind was already set.

The next testimony of Tajuddin's mental make-up and exceptional leadership quality is his first meeting with the then Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. The importance and gravity of this meeting cannot be overemphasised. It sowed the seed of a crucial partnership that sailed us through the following crucial nine months of genocide and brutal war.

Here was a man bereft of literally everything except his self-respect and faith in his people's desire to fight for freedom and the willingness to die for it, sitting face to face with the powerful prime minister of the biggest country in the region—with a most famous dynastic heritage—making a case to assist us in our fight for freedom.

According to Barrister Amirul Islam's account published in Aloker Anantadhara (Vol 1, Pg 69), Tajuddin said, "… This independence war is ours and we want to do everything ourselves. What we need from you is shelter for the Mukti Bahini in the Indian soil, facilities for training and arms supply. Within two to three weeks there will be a huge influx of refugees whose shelter, safety and food India should help us with. We also need help to let the world know about our independence struggle. We also request your help in the field of diplomacy." The war, he said, was ours. He didn't want it to appear to be an India-Pakistan war, nor a civil war within Pakistan. It was our war for freedom and independence.

The most serious decision that Tajuddin had to urgently implement was the formation of some sort of internationally acceptable government-in-exile so that our war acquired legitimacy, a visible existence, a command structure that was both representative and authentic. Such a set-up would expedite the process of international recognition and receiving assistance.

This proved to be a serious challenge because of internal dissension. The younger leadership led by Sheikh Moni and Sirajul Alam Khan (as well as Tofail Ahmed, ASM Abdur Rab, and some others), which had emerged quite powerful during the non-cooperation movement of March '71, demanded a revolutionary government. This would give them far more power and manoeuvrability than otherwise. This contrasted with the more mainstream view, carried by Tajuddin and other senior leaders, of gathering a large number of the elected 167 central and 288 provincial members of parliament in Calcutta and forming the government-in-exile with their support.

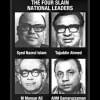

In forming the government, Tajuddin's formula was to follow the same leadership group that operated under Bangabandhu during the non-cooperation movement. Opting for a presidential form, making Bangabandhu president and Nazrul Islam the acting president, Tajuddin as the prime minister and M Mansur Ali, AHM Qamaruzzaman and Khondakar Mostaq Ahmad as ministers, helped to solve the problem for the moment.

However, the Sheikh Moni-led younger group, though forced to accept Tajuddin's formula, continued their efforts to create dissension against him. He was contested and contradicted in every turn of events, which became very serious with the formation of Mujib Bahini.

Prof Khan Sarwar Murshid's piece in Aloker Anantadhara elaborately depicts the problems faced by Tajuddin's government due to the factions within. In addition to Sheikh Moni and the student leaders, among the seniors the role played by Khondakar Mostaq was quite troubling. He demanded the foreign affairs portfolio, forced the Mujibnagar government to allocate a special office separate from the rest, and compelled Mahbubul Alam Chashi and Taheruddin to be brought to Calcutta and included in his team in the foreign office. Both their names surfaced after Bangabandhu's assassination in August 1975, in which Mostaq took a leading part and was made the president of Bangladesh by the killers.

One of the extraordinary examples of Tajuddin's leadership and management capacities is the way he ran our armed struggle—our Muktijuddho. This was an area totally unknown to any politician, including him. Setting up the 11 sectors and around 70 subsectors, creating their respective leadership structure, and assuring the supply of arms and ammunition, food and training were enormous tasks. Our own sector commanders came from Pakistan-trained armed forces whose values, attitude and command system all came from a highly centralised army structure, which did not suit the needs of guerilla warfare—something that was the need of the moment. In spite of their background, our sector commanders did a stupendous job for which they have not been given appropriate honour.

Tajuddin played a tremendous role in terms of inspiring and motivating our forces and giving them that crucial psychological and emotional support that troops needed at such a crucial moment in history. Tajuddin, who visited the war zones, built a very warm personal rapport with the freedom fighters.

One of his biggest successes was negotiating with the host country, India, and keeping the supply of arms and ammunition going, though not as much as we wanted and needed. Obviously, here the Indian decisions and actions were determined significantly by their own strategic considerations, but Tajuddin was able to always put our needs successfully forward and get his way to keep the operations going.

There are two initiatives of Tajuddin that are not well-known.

First was his attempt to create a platform to forge a unity of all political parties that supported the freedom struggle. He held a meeting in September with the leaders of various parties, including Maulana Bhashani, Muzaffar Ahmad, Comrade Moni Singh, and others. This was an astute move that greatly strengthened the image and prestige of the government-in-exile, especially globally.

Tajuddin also thought ahead and made advance plans of reconstruction and rehabilitation to be implemented after the creation of Bangladesh. His most significant project was to create a militia force consisting of all the freedom fighters. The idea was to turn the young who took up arms to defeat the enemy into a massive force for nation-building. He did not want to send any freedom fighter home empty-handed but to engage them to build the Sonar Bangla of our dreams.

As we pay tribute to Tajuddin Ahmad on his birth centenary, we must ask ourselves the critical question as to why this man's legacy has been so neglected till date.

The answer lies in the mockery that we ourselves made of our Liberation War history. As regimes would change, so would our history books, the national symbols, the heroes, and school textbooks. Just imagine the harm we have done to the younger generation by tailoring our most glorious legacy into party-centred narratives. Since no pro-Tajuddin party ever came to power, he remained uncelebrated.

Can any nation grow with such a short-sighted, dishonest and myopic view of history? The indifference and lack of respect we see today in the younger generation to the history of our Liberation War is caused, in many ways, by the personal and partisan games we played with our most sacred past, our independence struggle in which we faced genocide, ethnic cleansing, and the prospect of destruction as a nation, not to mention the huge number of lives we lost and many more millions who lost their homes and livelihood. When and how will our mind shift to fact-based authentic history? As I see the degradation of history, falsification of truth and false narratives replacing crucial ones, I wonder how we can rebuild our nation's history based on truth.

Mahfuz Anam is the editor and publisher of The Daily Star.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments