Time capsule: 1978 Mitsubishi Lancer

Photos: Rahin Sadman Islam

The story of this 1978 Mitsubishi Lancer Deluxe is scarcely believable not because of what it is or who owns it, but what it was used for. There is an overwhelming majority of people out there who treat an automobile for what it is: a four wheeled contraption to be relied upon as a daily appliance, a means to get around and do the things that have become second nature to humans - be driven to school, learn to drive, get a job, fall in love, get married, drive kids to school, be a productive member of society. For most people out there, a car is a tool on this journey through life, the kilometres on the clock ticking by at almost the same pace as their time on this planet. Stopping that clock ticking, preserving it isn't really possble. Even slowing it down is only possible in the rare cases where every step is measured, special, and reserved for the most important things in life.

This Lancer isn't really special on its own, save for the measured pace at which it has been driven, making every last kilometre on the odometre count. This Lancer was never used for mundane tasks, not one of those 16,418 km's.

To put that figure into context is easy. The average reconditioned Toyota Axio or Premio sold in Dhaka has a mileage of around 15,000-20,000 km's, and they're billed to customers as practically brand new and are charged a premium for it. In that context, this Lancer is practically brand new, and rides and drives like a brand new car.

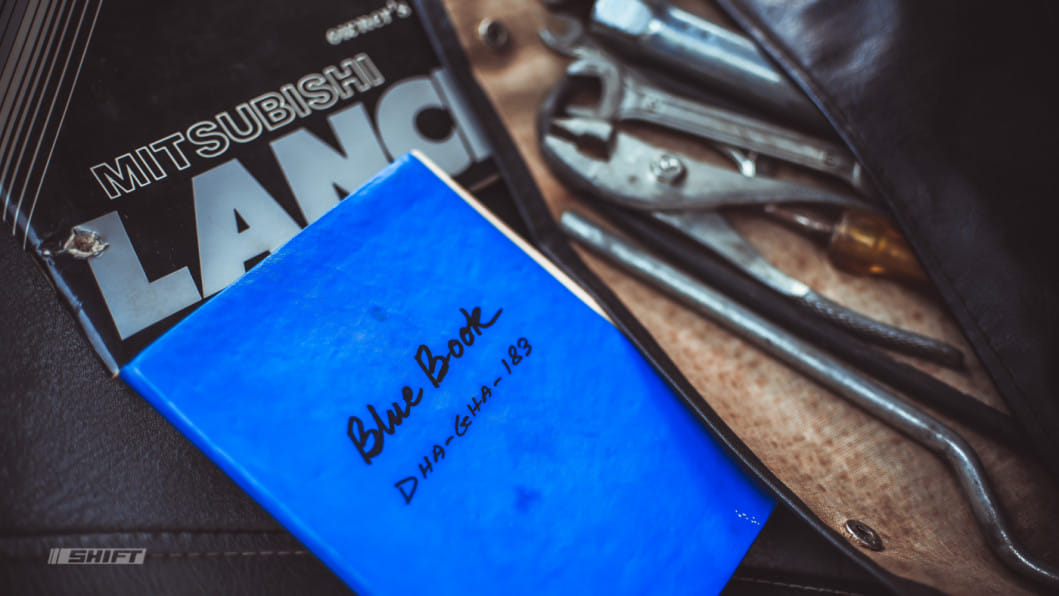

Md Shariful Islam Sunny is a business owner from Lalbagh and it was by a stroke of luck that he got to be the second owner of this pristine Lancer. His mechanic gave him a call and asked if he'd like to take a look at a classic car that was up for sale. On arriving at the address provided by his mechanic, he got the shock of his life – the Lancer, tucked away inside a clean garage, was flawless and in completely original condition. The bodywork had a few scratches and a couple of dents, but otherwise the car was a veritable time capsule, with original wheels and tyres, paint, interior and toolkit. Another incredible aspect to the Lancer was what was hiding in the glovebox – original owners' manual and service booklet, with detailed descriptions outlining the service work done on the car and the amount paid for each item, meticulously documented since 1979. Flipping through the service booklet, it's astounding to realize that the previous and first owner, Kazi Mahbubul Haque of Road 12, Dhanmondi, had taken the time to document the service work when most people wouldn't have bothered with it. The service history also points to another fact: the car was serviced with 100 Taka worth of work in Dhaka in 1979, which means this 1978 Lancer was bought brand new and maintained as such since then.

That caring nature could clearly be seen by how the previous owner, now in his 70s, handled the sale of the car as he notified Sunny of the faults on the car - a weak tension spring on the rear left drum brake. That's it. That was the only issue, aside from failed paperwork which has since been updated.

Looking at it, the first thing you notice is how straight the bright blue bodywork is. Covered in a well-aged patina, the Lancer's bodywork is straighter than most "new" cars today. The doors still close with the solid thunk you'd expect from steel bodied vehicles from that era, and the lack of difficulty in closing them points to the fact that this car has never had any work done on it. The chrome bits are shiny, original and scratch free. The fantastic front grille is dead straight and still gives the car the sleekness that made it stand out from its Japanese competitors like the Toyota Corolla KE and Datsun 120Y. The wheels are small and prim, and carry a stylised Mitsubishi "M" logo that anyone would confuse with the Isuzu logo at first. They're still wrapped with the Dunlop tyres the car came equipped with from the factory. Risky, but original.

Inside, you're treated to uncovered seats that look and feel new, while the thin doorcards and manual window winders are still well put-together and not flimsy or fiddly as they usually are after decades of use. The original floor mats are still in place, and tiny details like the intricate patterns on the back of the headrests are well preserved. Of-course, given the condition of the rest of the car, you'd expect the original FM radio to work, but actually seeing it function without any hiccups at all, 40 years after it was made in a factory in Japan, is still quite a big shock.

It starts on the first try, without coughing, every time. The 1200 cc 4G36 straight-4 cylinder motor turns over with the softest of purrs, and the Lancer moves forward with the least amount of resistance thanks to the smooth 4 speed manual gearbox putting about 55 HP of power to the ground. That number doesn't seem like much, but considering the minimal wear and tear this motor has faced over the years, it's safe to say most of that mechanical horsepower has been retained. On the move, the Mitsu is quiet, composed and glides over bumps and potholes with ease. It's very disconcerting – you expect continuous shaking, rattles and creaks because your eyes tell you you're in an old car, but your ears and body send completely different signals as you realise this Lancer shows none of the signs that this is a four decade old car.

Shariful Islam Sunny has one goal: to keep this car running for as long as possible and treat it with utmost respect and care. It's not often that you're put in charge of maintaining an actual, real-life time capsule, and it's not a responsibility to be taken lightly and he knows that. He'll make sure this Lancer survives for another 40 years and that every last kilometre is worth putting on it.

A fellow classic car enthusiast very recently asked the hapless writer of this article why this publication bothers featuring these kind of cars and the people behind it. With no obvious answer at hand, there was an uncomfortable silence which could not be filled by furtive sips of coffee. Now though, after reflecting on the topic in the context of this beautiful Lancer, there might be a satisfactory answer.

We do these features and love these inanimate chunks of metal and steel because parts of us remain with even the most mundane of objects when we aren't around anymore. It's our best shot at leaving something behind, when the clocks stop ticking and the ride's over. Everything else is impermanent, too dynamic to call a legacy, too fragile to be placed on a pedestal. For some, it's buidlings and art and poetry and literature. For others, like us, it's a three-box shape with four wheels.

Comments