The price of victory: 1971 and the mental health of a generation

Tales of the Liberation War of 1971 have been table talk in my household for as long as I can remember. Both my parents and their siblings – most of whom were in middle school at the time – have an abundance of memories to share, some heart-breaking, some infuriating, and some even amusing. But what has never been discussed is the impact of these memories, the persisting scars they left in people's minds long after the war was over, and so last week, I finally asked.

My father was only thirteen when he found out his father had absconded in the middle of the night on March 26, 1971.

"Bangabandhu had started asking his closest aides to go into hiding around late March," he recounts. "Abba being a high-profile politician meant we were more aware of the political tensions brewing behind the illusion of potential peace talks with the central government that year, and I think that made the war harder for us."

Mohammad Ullah, former President and Speaker of Bangladesh, is my grandfather. His years of experience in state affairs prior to the war had prepared him for such turbulent times, but in his absence, my grandmother was left without guidance and had to fend for their five children all on her own.

"For months we had to rely on hearsay to know where Abba was, and sometimes we even heard the places he was staying at had been bombed. But thankfully, we soon learned from a reliable source that he was safe with several comrades in India and that he had asked us to join him," my father said.

After a five-day boat journey, the family was finally reunited. However, my father still wonders about all the things that could have gone wrong.

"At one point of the travel, locals had stopped us for interrogation; they assumed we were a Bihari family because of me and my sister's complexion! Besides, Amma was only thirty-five at the time and that was such a difficult time for women and young girls, too. I have no idea how she managed all of this by herself."

As for the mental effects of the war, he says, "It isn't something I always think about, but it does creep up on me sometimes. Especially the horrors of it."

Similar stories of grief, fear, and uncertainty are all around us.

Shaheen Hassan was only twenty when he had left his home to liberate the country.

He recalls, "The Pakistani military personnel were capturing people – especially young men – left and right and killing them without a thought. My mother decided if her sons were going to die, they might as well die an honourable death, fighting for their motherland. So, me and my younger brothers, along with some cousins and an uncle (Bir Uttom Captain Shahabuddin Ahmed), went to war. That's just how resigned we were to our impending death at the time."

Today, like my father, he remembers the terrors of the war sometimes. "You can't ever really forget the gravity of such crises, you know," he says wistfully.

Dahlia Khan* was in her early twenties during the war and is a survivor of sexual harassment at the hands of the Pakistani military. "Frankly speaking, dying mattered less to girls at that time. The fear of being raped was much greater. I am thankful to Allah that I nearly escaped that fate, but I still wonder what could have happened at times."

These stories encapsulate the horrors of war, where even the loss of life might seem like a more acceptable fate compared to vile acts of sexual assault.

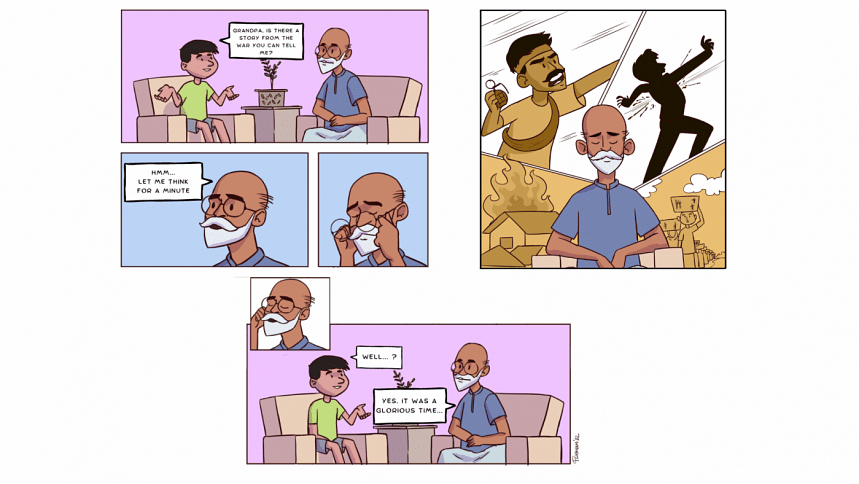

Despite their range of experiences of the war, everyone interviewed for this article had one shared opinion – the younger generation is losing touch with Bangladeshi history. But as Hassan points out, there is no single generation to blame here. He explains, "Soon after the successive military coups and ultimate government takeover in the mid-70s, anything that discussed the Liberation War – books, movies, forums, celebrations – were virtually banned. And since military presence in the government was strong for many years, the ban was made to last long as well. This in turn led to multiple generations unintentionally growing up without learning much about the country's history and the Liberation War."

My father shares a close perspective, "Sheikh Mujib's untimely demise certainly spelled doom for our nation's collective patriotism and morale. He knew how to draw people in for a cause, and few leaders after him had the same charm. Hopefully the current administration's persistent focus on the Liberation War and its legacy will serve to attract the youth's attention and educate them adequately."

But when it comes down to sharing the mental disturbances the war left on them with younger people, virtually all of them had the same attitude: it's nothing important. "At the end of the day, every one of us went through stress during that time, and it's only natural. It's war, after all. But I don't see what there is to really discuss here," Khan explains.

Perhaps it is the case for many, but there are also exceptions. In the early 90s, decades after the war, a neighbour nearly physically attacked my uncle because he had unwittingly served the neighbour a bottle of Pakistan-manufactured juice. That man had lost his eldest brother in the war, and hence his reaction. For many, whether they acknowledge or even realise it, scars remain.

It is no secret that mental health is very taboo and rarely ever discussed openly in our culture. The judgement surrounding this topic stems more prominently from older generations, but they are also the ones who have witnessed the worst human minds can conceive during the war. It then falls on us, the younger generations, to at least make efforts to reach out to them, to encourage discussions about not just war experiences but the enduring effects they've had on our loved ones. This shouldn't be done to simply be more informed citizens, although that is very important, but also out of love and respect for those who have gladly fought infernal pain to give their countrymen the greatest gift man can behold: freedom.

*Name has been changed on request for anonymity.

Fabiha is secretly a Lannister noblewoman and Slytherin alum. Pledge your allegiance and soul to her at [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments