A Small-town Story

There is something encouraging about discovering small-town Bangladesh. It reinforces the truth that big cities and grand institutions per se don't produce great works; individuals do. On a recent trip to Jessore, a district on the southern tip of Bangladesh, I had my horizon shifted by an unheralded gem of such an individual.

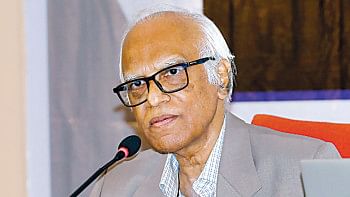

Everything about Ekram-ud-daullah, editor and publisher of the Dainik Kalyan is old school. In a career spanning 46 years, he has managed to remain uncontaminated by big money. "A lot of wealthy people show interest in investing in the Kalyan. But I want my daily to maintain its neutral stance. I fought in the liberation war and I run my newspaper in the spirit of independence," he says sitting in his small room that showcases numerous awards, mostly local. In 2004, he received the Ahmedul Kabir Gold Medal for progressive journalism.

The building that houses his office isn't much to look at. But don't let the appearance fool you. Journalism runs through his veins. "My father Moksed Ali wrote columns in the Statesman," he says lighting a cigarette. "Elder brother advocate Itim-ud-daullah was a progressive politician and the Jessore correspondent of the Daily Observer. Elder sister late Begum Ashrafunnessa was the publisher of Sadya Khabar from Khulna. Younger brother Rukun-ud-daullah is a senior reporter at the Daily Sangbad."

There's more.

His son Ehsan-ud-Dowla Mithun is a photo journalist at the largest circulated Bengali daily Prothom Alo. Stepping into his father's footsteps, Mithun did not see a safe job as an ultimate measure of success.

Ekram-ud-daullah started writing while a high school student. During that time he also worked as a compositor of a local press. "Before founding the Dainik Kalyan in 1985, I wrote for many local and national dailies including the Daily Ganokantha and the Daily Sangbad." Operating from four small rooms with a staff of 20—8 among them staff writers, the Kalyan has a circulation of about 4,000. "The main challenge we are facing is that we don't have our own press," he says.

The circulation number does not tell the whole story or the impact his daily has made. "In 1986, I wrote a series of investigating reports on how some members of the local police were selling confiscated smuggled goods for personal gains. The Officer-in-charge of Sharsha police staion threatened me and the Sub-Inspector offered me bribe. But I went ahead and published the reports. Eight cops including the Officer-in-charge and the Sub-Inspector were punished by the Martial law court."

Armed with a sharp pen and steel nerves, Ekram-ud-daullah is brave beyond belief. "In 1985, I wrote a report on the hooligans of Barandipara, then a notorious locale for gang violence. I had to relocate under threat of attack. Thanks to my report, 75 goons were sentenced." Three hours after the verdict came out; he published a 'telegram edition' which was sold out immediately. The newspaper used to be hand-composed then.

His commitment to change the society through writing is continuous. "Five years ago, the Jessore Municipality wanted to fill up the pond on Netaji Subash Chandra Lane and establish a market there. I thought it was a bad idea. What if a fire broke out? Where would the fire service get the water to extinguish the fire? So I mobilised public support to stop it."

The conscientious journalist believes there are not many jobs with a higher calling. "I am concerned about a lot of youngsters in Jessore taking up drugs. We have to create a better society. We have to build libraries, facilities for sports and cultural activities."

To Ekram-ud-daullah, journalism is a simple game. It is about finding things out, telling other people about them and holding people accountable. His is mostly a thankless job. But he does it well—day in and day out—without expecting anything for himself. He reminds me of the young woman who stands before a door in Turgenev's poem "The Threshold." When a voice asks if she is ready to endure cold, hunger, mockery, torture and even death, all of which await her on the other side of the door, she says "Yes" and steps over.

A voice from behind her cries out, "A fool." "A saint," utters another.

It is up to you to decide what to call him.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments