Home in the World: The Autobiography of a Well-Known Bengali

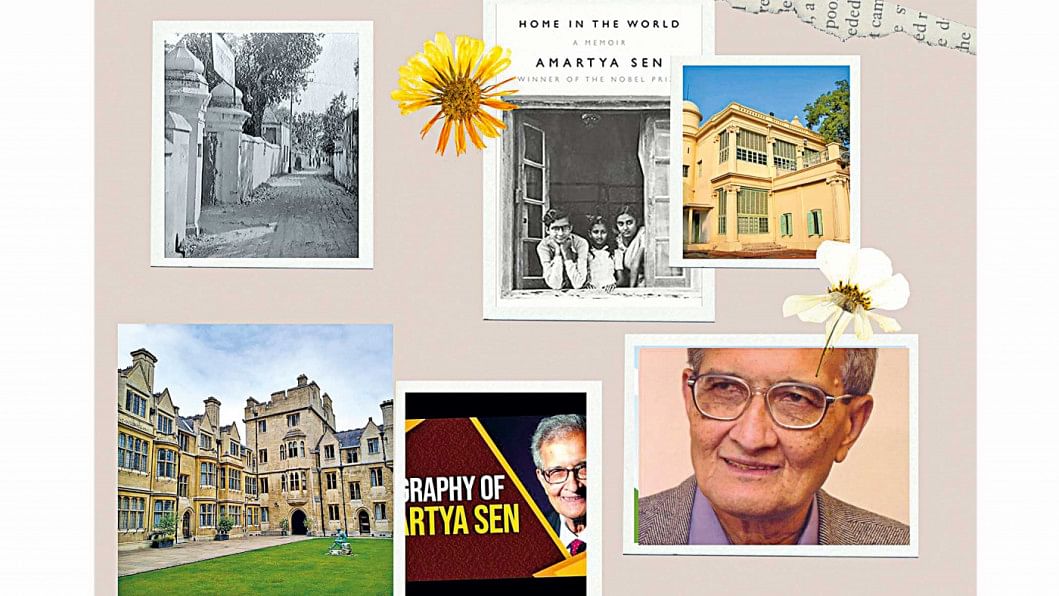

The dust jacket cover of Amartya Sen's absorbing and remarkable memoir shows him as a young boy, with his sister and a cousin at home, looking out at the world. An apt cover image of a fittingly titled book about someone who would be always taking in the world as he went all over it! As a student and a teacher—but also as an exceptionally gifted person endowed with a seemingly insatiable appetite for knowledge—he would make himself at home in the world mentally as well as physically. Not even past adolescence, we find him absorbed in a whole lot of issues as an economist, a social scientist and a humanist. As he matured, he would range over issues such as capability, social choice and social welfare, poverty and famine, and disciplines such as mathematics and economics. Advocating internationalism and highlighting the pitfalls of nationalism, Sen has written a truly enlightening book. As well, it shows the making of the future Nobel laureate through a very readable narrative. In short, this is intellectual autobiography at its best—readable, thought-provoking and continuously engrossing.

The range of the book and the memoirist's interests is vast and varied, as is Sen's intellectual peregrinations. Dhaka, Mandalay, Santiniketan, Cambridge, Calcutta, Delhi, Massachusetts, California, Boston and where not? Sen is an indefatigable traveler, somehow managing the time in between his scholarly pursuits and teaching assignments to travel also for travelling's sake all over India, Europe and the United States. He seems to relish too being part of addas, discussion groups, reading circles, seminars and lecture sessions. Indeed, here is someone temperamentally at home in the world, a citizen of it bent on picking up whatever he gleans from his contacts with peoples and places. Always, Sen seems intent on transforming whatever he sees and learns from his contact with people and immersion in places and his scholarship into ideas that will be of use to others. Everything he observes and does appear grist for the mill of an extraordinary intellectual on the make in what is surely the first volume of his memoirs.

Of his chief homes discussed in Amartya Sen's memoirs, I would like to focus on the five main ones here. His earliest memory of home is associated with Dhaka, although he was born in his Nana Bari or maternal grandparents' home in Santiniketan. Because his father taught Chemistry at the University of Dhaka, he was brought to the city soon after his birth. Quite understandably, he finds present-day Dhaka as "lively, sprawling and somewhat bewildering city," but remembers it from his childhood days here as "a quieter and smaller place." Home then was Wari and the school he initially went to was St. Gregory's.

wThe second of the homes this citizen of the world treasures is that of his maternal grandparents. Kshiti Mohan Sen, a formidable scholar and linguist and close associate of Rabindranath Tagore, was his maternal grandfather; he taught Sanskrit at Visva-Bharati. It will not surprise anyone who knows of Rabindranath's fondness for naming babies that the name "Amartya" was given to him by the poet. At his mother Amrita Sen's's insistence, Sen soon left Dhaka to be a student at Rabindranath's school. During partition, and when his parents finally moved to India, this became Sen's permanent "home." Though he would move to Calcutta for graduate studies and a teaching stint later, Santiniketan remained the still point of his ever-turning universe; his citizenship too would remain Indian. Indeed, the book ends if not in Santiniketan, with a reference to Rabindranath, whose thinking and example as well as school seemed to have been immensely formative in his thinking. Specifically, the reference is to the poet's last public lecture, delivered at the height of World War II in 1941, which he translated into English as "Crisis in Civilization" with the help of his grandfather. His grandfather had the responsibility of reading it out on behalf of the poet. The message of the speech—to opt for internationalism and not be hemmed in by nationalism—was germane to the thinking of the writer of Home in the World. So was Visva-Bharati's motto— "where the world meets in a single nest."

The third of Amartya Sen's homes that he dwells on at considerable length is Calcutta. He stayed here first for a long stretch of time when he did undergraduate studies at Presidency College before moving to Trinity College, Cambridge for more advanced studies. When he had finished writing his dissertation by the end of his first year—incredible as this may sound to anyone who has gone through a graduate program—and had submitted it for review, he was offered a job as the head of department of Economics at Jadavpur University. As Sen puts it with wry humor, he was then not yet 23 years old— "unsuitably young for that job."

The fourth of Sen's homes was Trinity College, Cambridge. Instead of doing a M.A. in Calcutta, he preferred to study as an undergraduate at Cambridge, He then did a M.A. and Ph.D. there. In course of time, he also became an Assistant Lecturer, a Senior Scholar and finally a Master of the College. The Cambridge years were very formative for the budding economist because here he came into contact with fellow scholars and teachers who shaped his initial thinking decisively. Among the fellow scholars he made friends with is our very own Professor Rehman Sobhan, whom he claims as "probably the closest lifelong friend" he ever had. He and Sobhan, and the distinguished Pakistani economist Mahbub ul Huq, were part of the lively Cambridge "majlis" which would assemble here for addas. But in Cambridge he met his chief mentor, the Italian economist Piero Sraffa and friend of Antonio Gramsci, the distinguished English Marxist economist Maurice Dobb, and other famed economists such as Joan Robinson and Denis Robertson. Sen tells us that in this fertile ground of economic thought he was drawn to them all, but not necessarily because their ideas were indispensable to the evolution of his economic thought. He would forge his own path through this intellectual maze created by contesting economic beliefs of "the neo-Keynesian and the neoclassical schools," not to mention the Marxist one.

The fifth of Amartya Sen's home would be in Boston, for he was offered a visiting teaching position at MIT's department of Economics, coincidentally when his first wife Nabaneeta Dev Sen, of Jadavpur's Comparative Literature department, would be doing research at Harvard. Sen, would later become Thomas W. Lamont University Professor and a professor of Economics and Philosophy much later. As always, he made good use of his first period of extended stay in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to exchange ideas with Nobel prize winning Economics laureates such as Paul Samuelson and Robert Solow and other economists who met in MIT's Faculty Club regularly. Here as in Santiniketan, Calcutta and Cambridge, he profited from an atmosphere where "intellectual stimulation" would be combined with relaxation. Indeed, his first stay in Cambridge made Sen, as he puts it so drolly, "academically greedy" so that henceforth he would opt for what he calls "a mixed life" divided between India, England and the United States.

Home in the World is thus an extended portrayal of a brilliant polymath—an economist, and social scientist—as a young man, but dispersed through the autobiographical narratives are fleeting accounts of his personal relationships—with his parents, first wife, his children and friends. But Sen writes also about the few dark stretches of his life, such as the time during his Calcutta student days when he had to contend with the onset of cancer—for the first time. But his is, nevertheless, a very engaging portrait. A Bangladeshi reader, surely will be particularly pleased to read the narrative of an international celebrity who answered spontaneously to a question about the language he dreams in, "Bengali, mostly." But it is, above all, delightful to read this lucid account of a true citizen of the world as well as a leading global intellectual.

Fakrul Alam is Supernumerary Professor, Department of English, University of Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments