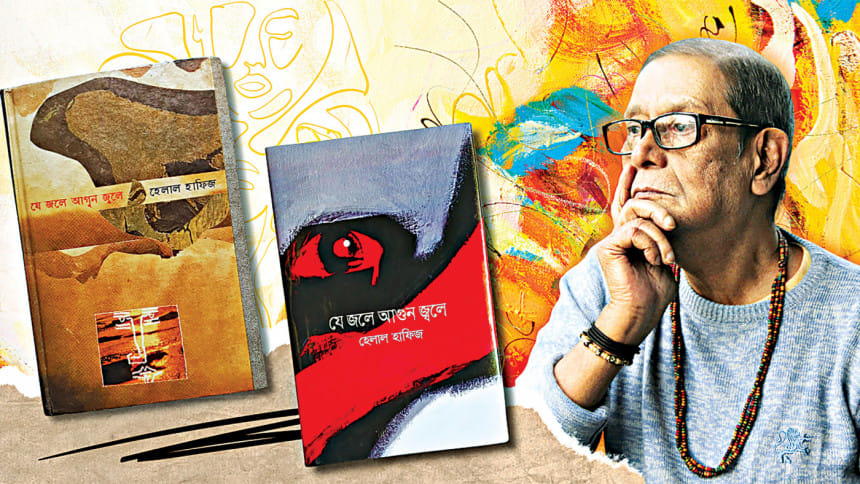

‘Je Jole Agun Jole’ was first published under the title ‘Kar Ki Noshto Korechilam’

It is a rather rare feat to find poetry composed in Bangla and compiled in the writer's only published book that has propelled both the poet and book of poetry to the height of fame and immortalisation, that too in the poet's own lifetime, as Helal Hafiz's Je Jole Agun Jole has done.

The first two lines of "Nishiddho Shompadokiyo"—written during the 1969 mass uprising, in the period of unrest preceding the great pains of a nation waiting to be born—read:

"Ekhon joubon jar michile jabar tar sreshtho shomoy

Ekhon joubon jar juddhe jabar tar sreshtho shomoy."

Composed on February 1, 1969, these lines then spread across the region, from the walls of Dhaka University to every nook and cranny in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), serving as a mantra for freedom and the Liberation War.

Helal Hafiz was born in Netrokona, a paradise where beels, haors, clouds, and hills converge. It was in this heavenly place that the poet spent his childhood, adolescence, and the early days of his youth.

In 1967, the poet set foot in Dhaka and enrolled in the Department of Bangla at Dhaka University, where he resided at Zahurul Huq Hall. After completing his studies, he took up work at the Dainik Purbodesh, Dainik Desh, and Dainik Jugantor newspapers, and spent much of his life in addas at the Press Club. Hafiz opted to spend his nights in a room at Karnaphuli Abashik Hotel, located on Topkhana Road, opposite to the Press Club.

In 1986, the poet published his first book of poetry, Je Jole Agun Jole, at the age of 37. In Dhaka's Bangla publishing scene of the time, it was the age of the letterpress. Each page was typeset using lead type, and the collection of 56 poems was printed at Modern Type Founders and published by Nazmul Haque of Anindya Prokashan. The cover illustration for the first edition was done by Khalid Ahsan. As the letterpress era drew to a close, computerised printing took over in its stead. Although Anindya Prokashon ceased operations, the book was reprinted in 1993 by Dibya Prakash, with a new cover by Dhruba Esh. Since then, numerous reprints of the book have been published.

Now, as the age of print itself seems to be reaching an end, future editions of Je Jole Agun Jole are likely to be published as e-books. Of course, the book will only truly be imprinted upon its readers' hearts—etched in the many loves and sorrows of lovers' hearts, and in the marches and slogans of revolutions and their revolutionaries.

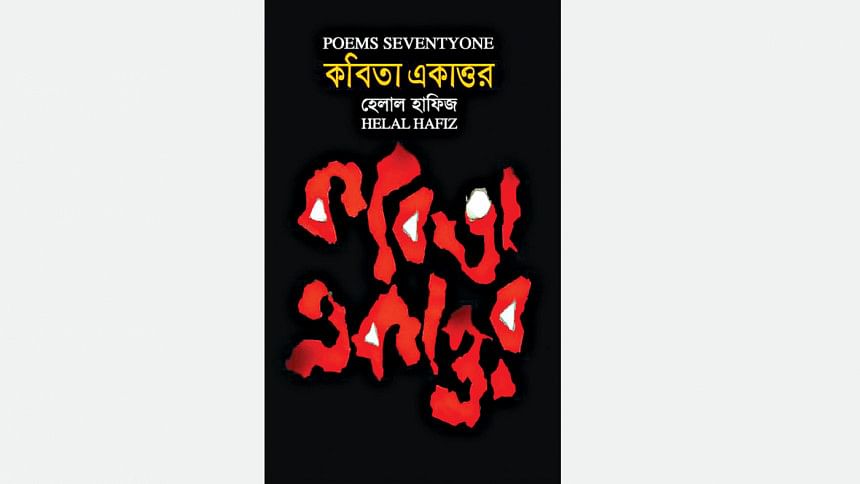

Several years after Je Jole Agun Jole was first published, in 1996, a collection of 12 new poems was published in Ochol Premer Podyo, illustrated by Khalid Ahsan. In February of 2012, a bilingual poetry book, titled Kobita Ekattor, was published at the Ekushey Boi Mela, featuring translations by Jubak Anarjo. Adding 15 new poems to the initial 56 printed in Je Jole Agun Jole, the book contained 71 poems in total, and as such was named Kobita Ekattor, or Poems Seventyone. It was published by Ramshankar Debnath of Bivas Prokashon. In October 2019, his second original poetry collection, Bedonake Bolechi Kedo Na, comprising 35 poems, was released. It was published by Dibya Prokash with a cover design by Dhruba Esh.

We can derive much about the poet's life from his own words. On the 75th anniversary of Helal Hafiz's birth, his followers arranged a celebration at Dhaka's Bishwo Shahitto Kendro on October 7, 2022. Helal Hafiz spoke at the event, and I revisit a part of his speech for our readers today:

"Amake na chena maane

Shokaler shishir na chena

Ghashphul, rajhash, udbhid na chena

Gabhin kheter ghran, joler kolosh kak

Polimaati chena manei amake chena

Amake cheno na

Ami tomader daaknaam

Ujar Jamuna."

"I am an insignificant man," he said. "I had started my life with a tremendous dream, albeit a dream, a 'shopno' in which the 'sho' lacked a 'bo-phola'.

As a child of only three, still lacking awareness, the day I lost my mother was utterly incomprehensible to me. I had been deprived of the greatest love in the world.

There are no memories, no words, and no scripts. As the days passed me by, I steeled myself. I had vowed revenge against nature. The pain I confronted and the torment I endured in doing so—I am incapable of putting words to such agony.

And as the days passed me by, as I grew older, the pangs of motherlessness grew all-consuming. My childhood, adolescence, and finally, my youth. I had always been sports oriented, but the more I aged, the more the pain consumed me. Not being able to keep the pain at bay through just sports, I turned to the world of writing. That life of writing hasn't been insubstantial, of course. I have lived for 75 years. Not many are given such a long life. But I haven't been able to put it all to use. Some of it has been wasted. Not some, I've wasted enough time. And for that waste, I am ashamed, sorrowful, and to my nearest and dearest here today, I ask for forgiveness without an ounce of hesitation.

I've written very little in my life. But I have spent my life writing. This was my intention, the destination I had set for myself. Back then, in the '70s and '80s, books would be released in the three or four hundreds, which has now surpassed the thousands. The day after Boi Mela ended, you would not hear of a single book again. You would not hear of a poem that had been published, or lines from a verse that had been written. This distressed and concerned me greatly. I decided to write very little. It did not matter if the number of books I wrote was very few. But I wanted to write poetry that would last beyond the transient fame of the fair, poetry that would be read at one fair after another. Books that readers would remember, which would lodge themselves and be given life between the readers' minds and hearts. In 17 years of writing, from among the five or six hundred I wrote, I picked out 56 poems in a year and put together the manuscript for Je Jole Agun Jole.

The book had initially been published under a different name. But it wasn't a title I found satisfactory, though I had come up with it myself. It continued to pester me. That was why, even after the first copies were printed, I paid out of my royalties for the book's title to be changed to Je Jole Agun Jole before publication.

We hear stories of divine inspiration. Believe me, that was precisely how this title had come to me. I can't express in words how I felt the day it struck me.

I dedicated a lion's share of the life I've lived to poetry. I've thought of poetry as a guiding star. And the love, adoration, and honour I've received from the people of this country is unrivalled. Incomparable. It is not just this generation, but rather the entirety of human civilisation that wants to earn and save money. But I didn't want to gain either wealth or status through my poetry—I only wanted to gather people.

In trying to do so, the experiences I encountered have also been woven into a history of unspoken pain. Poetry has given me so much. It is a debt I cannot pay off in this lifetime. Your love has transformed me from grass, from saplings to ever growing plants. I bow with a humble heart. I have only learned to bow. I only wish to bow; I only wish to bow."

Kamrul Hasan Mithon is a writer and photographer.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments