PeaceCity alley

The Notorious Loverboy, Slum Boy and Millionaire's Daughter, My Bride or My Mother, My Mother's Body in a Wedding Saree, The World is but a Slave to Money: ranging from melodramatic, to very questionable, to staunch philosophical critiques of capitalism, we could never guess what new film title and its vibrant, maximalist collage-style poster would greet us as our silver Toyota Corolla would swerve into a narrow alleyway and stop in front of a wholesale clothing market. We were home from school.

The entryway to Shantinagar Goli, on which my childhood home stood, was sandwiched between two of these wholesale clothing markets. On top of Gazi Bhaban market stood a 15-floor apartment building, and on Pallwel Supermarket stood Jonaki Cinema Hall, boasting the aforementioned posters on its facade. We rented a 2450 sq feet flat on the 14th floor for 20,000 taka per month from the Gazis. The Gazis were an influential old Dhaka family. According to urban legend, their forefathers had fought off tigers with their bare hands from the land where Gazi Bhaban stood.

I spent my days after school longing for the weekend, when a parent could accompany me outside. No little girl was allowed to go out into these streets unaccompanied. Past midnight on Fridays, we heard sports cars speed out of Shantinagar Goli, the children of the Gazis going out for the night. My parents pursed their lips. Preparations for the Friday prayer started early: road swept clean, open drains closed with lids (which would be stolen by the end of the day), cinema hall posters covered with black fabric, and a long roll of white fabric covering the length of the road; the goli was transformed into a communal prayer space. The mosque was on the main road, and by the time one o'clock struck, all the alleyways in the neighbourhood were filled with panjabi and tupi-clad men arranged in uniform rows, ready for the weekly Jummah Namaz. The story of this street is the story of its coexisting duality.

A good couple of hours post prayer, when the crowds were cleared and the prayer mat rolled up, I clutched Ammu's hand as we swerved and swivelled through the swarming crowds on Shantinagar Goli. Back to back and wall to wall, we passed more apartment buildings: several "Ma groceries"; "Ma's Salon"; a small beauty parlour; a dentist's office; and a tandoori chicken shop where the nice uncle (but a wifebeater behind closed doors) rhythmically rolled out dough, aggressively stuffed it with potatoes, and directly dropped it into bubbling oil, frying endless samosas under open air. Throughout the length of the goli, bundles of electrical wires, tangled and bulging, hazardously hung roughly 12 inches above our heads. As we walked, questions regarding Baba's health and my school were yelled at Ammu from all around, everyone addressing her as bhabi, and Ammu cordially yelled back her answers. In Shantinagar Goli, people from all walks of life and socio-economic backgrounds shared its constricted space. The story of Shantinagar Goli is the story of flourishing in its unprecedented collaboration.

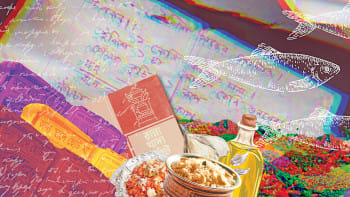

Finally, at the far end of the street, we approached the hawkers selling second-hand books from wicker baskets—Bangla ones for 20 to 40 taka each, but open to haggling, and the second-hand, locally pirated English books for 100 taka each, fixed price. The hawker uncles demonstrated a metaphor for our society. We valued a language that was once imposed on us in return for the riches of our motherland over the language steeped in the history of our land and our roots. Roughly three kilometres from Shantinagar Goli, students at the University of Dhaka had given their lives during the Language Movement of 1952, for Bangla to be restored as the state language of then East Pakistan. At 10, I lamented what had caused us to lose that glorious sense of pride in who we are and what is ours. The story of this street is the story of its subtle betrayals.

On very special occasions—Eid, birthdays, and the good report card days—we entered a three-storey high-end bookstore selling imported, brand-new English books, starting from 800 taka each. The aforementioned hawker uncles sat at the foot of this building. At this store, I would only buy a book I wouldn't find on the baskets outside.

We shopped for our clothes during Eid from the malls beneath our home, feeling very proud of ourselves when friends and family bought less nice clothing for over three times the price from elsewhere. Owing to the malls in our area being wholesale, we could buy directly from the supplier before they supplied to retailers all over Dhaka. The story of this street is the story of its intricate economic choices.

We couldn't take home any of the money we saved, though. In shipment cartons, with the clothes came very unwelcome "guests" and infested the homes of the residents of Shantinagar Goli. We spent hundreds weekly on insect repellent. As no spray could fully eliminate the unceasing, cyclic shipments of cockroach, we shared our homes with the survivors amongst them. One day, at six months old, as I sat on the kitchen floor while Ammu cooked, I grabbed a scuttling object from the floor with lightning speed. The story of this street is the story of how my first solid food was a cockroach.

The name Shantinagar Goli is ironic, as cockroaches were the least of the sources of o-shanti at Shantinagar Goli. The goli opened into a road on which administrative offices of the Bangladesh National Party stood. BNP was then the only surviving opposition to the Awami League, which has been the ruling party of Bangladesh since 2009. Periodically, BNP would call for strike action. By virtue of its location at the eye of the storm, for the children of Shantinagar Goli, such an announcement meant no school. Party workers would gather before the offices hoisting placards. The police would charge at them with batons and tear gas; the Party workers would return the favour and set fire to many rickshaws, a few buses, and a couple of private cars. The more an uninvolved civilian had to lose from the violence for the sake of it, the higher their chances of being affected would be.

In my naive selfishness of childhood, I would scan the rolling news updates beneath Ammu's nightly soaps, anticipating a leisurely day at home under my parents' protective watch, and rejoice at news of imminent strike days. The story of this street is a story of deriving joy from the most contradictory of sources.

One time, it rained sugar on Shantinagar Goli. But it only fell on me. Aunty on the Other Side of The Street was making a rich payesh, spiced with cardamom, cinnamon sticks, and grated coconut. Rice in the milk boiling on her stove, she realised she was out of sugar. Aunty on This Side of The Street took the only natural course of action, tying a half kg bag of sugar to the end of a pole and extending it towards Aunty on the Other Side of The Street through her kitchen window. Except that a pack of crows attacked the foreign object in the sky, and I was blessed with Divine Sugar.

Where we now live, we get missing ingredients promptly home-delivered to cook piping hot meals that lack the warmth of community spirit. The people of Shantinagar Goli kept no score of the ingredients, acts of service, and cooked dishes they shared. The story of this street is the story of its unchecked generosity.

Every year, it became increasingly unfashionable to live in South Dhaka. Businesses and schools shifted to the suburbs, like the localities of North Dhaka, and many families with young children, including mine, went with. I feel that if I were born and raised in these parts, I'd always have playgrounds, better schools, and cockroach-free homes, but never really feel the essence of being a Dhaka-ite and a Bangladeshi. Nor would I be bi-deshi, and live somewhere in between. I'd complain about the country, its traffic and its bureaucracy—as I still do now—but I never would have lived a life so aligned with my country's beating heart. In one of the most densely populated golis of the world's sixth most populous city, the story of this street is the story of my gratitude.

Amrin Tasnim Rafa is a former Sub editor at the Campus, Star Youth, and Rising Stars pages of The Daily Star and a soon-to-be freshman at Kenyon College.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments