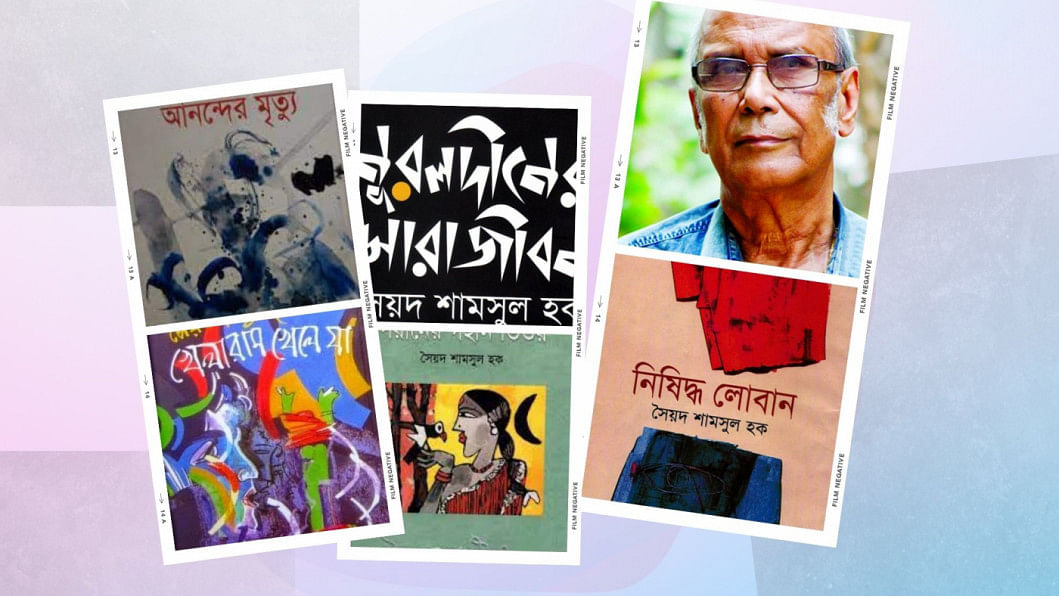

Remembering Syed Shamsul Haq

Being a 'sabyasachi' writer (literally meaning an ambidextrous writer) is not easy, and one cannot become such a writer without a proper set up. Syed Shamsul Haq's (1935-2016) life witnesses that being born as someone does not mean much; it is the process of 'becoming' that is important. Born as the eldest of eight children in an ordinary middle-class family, Haq could grow as one of the most prolific and versatile writers of Bangladesh, perhaps because of his exceptional literary talent and a few influences in the process of his becoming. He was an extraordinary observer and that is why he picked materials from his surroundings and used those in his creative writings.

Haq's first influence was his father, as we come to know from Tin Poysar Jyotsna (The Three Penny Moonlight), his autobiography. He writes,

"I have come this far through writing, but when did I begin? In that tin-roofed mud-hut, we used to sleep on a huge bed – I on Baba's right, and then all my siblings, and at the end Ma would be squeezed by the steel cabinet; on such nights I would wake up and see Baba at his desk. He was the first Muslim to write seven books on homeopathy. I still hear the crisp sound of Baba's writing; I can still see his illuminated lotus face in the dark." (11)

Syed Siddique Husain, Haq's homeopath father, belonged to a peer (Islamic saint) family, but he parted with family traditions and pursued English education. Leaving behind his Muslim aristocratic identity, Haq's father came to live in Kurigram to practice his profession. That decision offered an opportunity of experiencing Kurigram town, which Haq happily accepted. At that time, many students used to come to Kurigram town for their matriculation exam. Haq's father used to keep four or five such students as paying guests. Some of those students used to write poems, and Haq had his early inspiration from them.

After his primary education at Kurigram High English School, he moved to Dhaka in 1948, and resumed formal education at the Collegiate School. He matriculated in 1950 with distinction in Math and his father's wish was that he would study medicine, but he did not agree to study science. He was a whimsical person and his poetic imagination used to drive him from one place to another. That is evident in his sudden decision to go to Bombay to work as an assistant to film director Kamal Amrohi who was then making the film Mahal. The was in the year 1951. The 1950s was a tumultuous phase for the East Bengalis who claimed a distinct nationalism through their literature, politics, music, and painting. The martyrdom of young students for Bangla language in 1952 inspired Haq to return to Dhaka. He enrolled at Jagannath College as a student of Arts, and eventually enrolled at the Department of English at Dhaka University. However, he had to leave without completing his degree after a falling-out with the powerful Head of the department.

Both Kurigram and Dhaka inspired Haq's literary imagination. The loneliness of adolescence that he experienced when he first came to Dhaka, was vivid in his memory. He would often miss the greenery of his village and the people talking in local dialect. These memories accounted for the predominance of rural settings and the dialect of Rangpur in his writing. "Jaleshwari" is the name he uses for his birthplace, to which he ceaselessly goes back. In utter loneliness of the big city, he would walk the streets of old Dhaka, observing each detail of the narrow lanes and activities of people. This has influenced much of his creative imagination.

Another inspiration in Haq's literary career was perhaps his meeting with the leftist thinkers of his time. In his autobiography he mentions a ninth grader at his school in Kurigram, a boy named Pinu who used to write poems in red ink because red is colour of revolution. This boy seems to have impressed his young imagination. He also refers to Shawkat Osman who once told Haq, "Many worthy writers do not make it to the end. There are ninety-nine dead bodies behind one successful writer. Bengali Muslims cannot nurture their merit. Their creative selves wither away when they take a job and get married." Pinu Bhai, the boy from Kurigram, reappears as a typist at the Daily Ittefaq, whose poetic talent was lost in the hurly burly of the city and family life. Haq was close to contemporary writers like Abul Hussain, Shamsur Rahman, Shahid Qadri, and so on, who greatly helped him find his own voice as a writer.

Haq wrote mostly about the psychological tension, the tug of war between ideology and poverty, the struggle of the middle-class men and women in Muslim Bengal who existed on a dagger's edge – either live by corruption or die. Through a shifting focus from the lower class and rural setting to urban middle and upper classes, Haq's writings portray how corruption crept into the psyche of people in post-independence Bangladesh. These were, nonetheless, the major themes in other contemporary writers. It does not mean that Haq imitated any of his great contemporaries. He created his own diction, which is evident in his plays like Payer Awaj Paowa Jaye or Nuruldiner Sarajiban. Poraner Gaheen Bhitor is also a strong evidence of the distinct metaphors Haq constantly created, which was his own only.

September 27 is the sixth death anniversary of this great writer, and let us take this opportunity to invoke him - "Isn't the universe throbbing in your wounded heart? / They send for you once more/ On this silver, moon-washed night why have you bolted your door?" (lines quoted from Poraner Gaheen Bhitor, translated by Sonia Nishat Amin).

Sabiha Huq teaches English at Khulna University, Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments