The sarees and the stories we inherit

As a young girl growing up in Dhaka, I never found my foremothers in the books I read. Not unless those books were about bloody rebellions and violent wars in which the women end up as the spoils of battle, their stories mere footnotes on the pages of our history. In South Asian literature, subjective experiences of women are most often fraught with pain and suffering. Their identities then become marked solely by the trauma they endure. And while these are the predominant, lived experiences of many women in such geopolitical conditions, there comes a critical period after, when the "modern" or "emancipated" woman must assert her own identity in a rapidly changing world.

But are the only stories worth telling of those with only remarkable achievement or remarkable sacrifice? Certainly those must be told and heard. But as a 20-something year old who has achieved neither and doubts that she ever will, I find myself equally drawn to stories of the "ordinary" women. I longed to know the Dhaka that belonged to my mother, my aunts and my grandmothers. Women whose sacrifices are unrecorded, except in the memories of those they loved and protected fiercely. Women who made few notable inventions other than recipes for their signature korma or embroidered quilts woven with the kind of patience that does not seem to have gotten passed down.

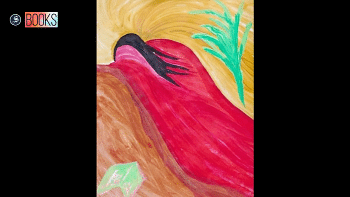

These are the women whose sarees I inherit, whose love and life fuel mine. And when I wear these sarees, I wonder often about the women who donned them before and the stories they carry.

It was only in my third year of university, in a class for South Asian Literature, that I came upon Razia Khan's The Enchanted Delta (2020). The story offers a rare image of Dhaka as the centre of a newly independent nation, as experienced by a 20-something year old woman named Selina. The events that unfold are simple and unremarkable. But through it, the author alludes to the pitfalls of building a new nation and explores the responsibilities of each gender in the collaborative creation of a new national and cultural identity. It examines the post-colonial hangover entrenched deep in Dhaka society. And it depicts, on a smaller, more intimate scale, the critical period of the post-Liberation era, which was foundational to the creation of the identity that we have since inherited. One that is constantly shifting even today.

I must admit however that it wasn't the pertinent questions raised about class privileges or the thoughtful rumination over the corrupt leadership that first made me fall in love with the story. It was getting to see a picture, a small glimpse, a microcosm of my mother's Dhaka, that made me greedily flip over the pages. It was the joy of experiencing, for the first time, reading a story that featured places of the city that both my mother and I have stood in the midst of, perhaps in the same exact spot, at very different times. I found myself underlining every casual mention of places like TSC, Banani, Gulshan 2 Circle, even the traffic jam at the rail crossing in Mohakhali, for no other reason other than the novelty of finding in a book, parts of my city from another time.

For the first time, I also found myself giddy over a male protagonist from the world of my father and uncles. The character of Nadeem, Selina's boyfriend, can be best described as a "man written by a woman". The interactions between Nadeem and Selina showcase a relationship of mutual respect and understanding where neither tries to undermine the other, which is refreshing to see in the portrayal of relationships between men and women in South Asian literature of its time. The first time Nadeem goes over to Selina's house reminded me that tenderness and romance does not belong only to the Darcys and Elizabeths of the literary world. Such references to women's desire or their inner lives are so rare in contemporary Bangladeshi literature that it took me entirely by surprise. From the flowers Nadeem puts in her hair, to the moments of tension passing between them in the form of longing gazes and charged silences to the culmination of all of this yearning into a passionate kiss. It reminded me that such romance existed not only in Victorian ballrooms and the English countryside but also right here, in the bustling streets and quiet corners of my city.

Interestingly, Selina is not from the margins of society but rather the very top. She is a woman of privilege, the bonafide "Gulshan girl". And yet every time she steps out of her privileged circle, she is haunted by the dualities of life in the city. At once self-aware and also deeply flawed, there is an air of superiority and a degree of hypocrisy in her perception of herself. On one hand, she proudly rejects Western conventions, choosing to wear sarees in Europe to represent her culture and promoting Bengali literature. On the other hand, she takes considerable pride in seamlessly fitting into English society and looks down on those who can't do the same. These details humanise Selina's character, raising important questions about the privileges of class and the hypocrisy of internalised otherness among contemporary, third world subjects. While Selina is a representation of hybridity or inbetweenness, other characters like Maruf and Sheila depict instances of colonial mimicry. It left me wondering how one can ever really define their cultural identity in this increasingly globalised, postcolonial world. And if doing so is ever entirely devoid of hypocrisy or appropriation.

I find history is often better understood through connections and parallels- between past and present, personal and public. It creates room for reflection that is unenforced. A story like The Enchanted Delta offers a refreshing account of the kind of personal history and feminine subjectivity that is largely absent in our literature. Much has changed in Dhaka since Selina's time and yet, like the traffic jam in Mohakhali, much has remained the same. To me, this story is memorable because it evokes a rare feeling of familiarity and representation: of imagining life in past versions of places I walk through today.

Selina, in her green-bordered Tangail saree, having kashundi and Pabda fish over sheetal mats, represents a story similar to that of the women in my life. Whose Tangail sarees and Rajshahi silks I've now inherited. And while the "desi fits" I source from my mother's wardrobe form an integral part of my own cultural expression, they are accompanied by the acknowledgement of the personal histories and unrecorded sacrifices that are contained within those six yards of fabric.

Montaha Absar is a writer from Dhaka, Bangladesh. Her work is primarily centred on the intersection between literature, theory, and personal reflections.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments