The dust storm

One day at the college the students were asked to wait by the football field. The Girls Guide Mistress would be inspecting us to find volunteers. She was a tall, pretty woman wearing a smart uniform of a white sari whose edge was fed through a belt loop on her shoulder. She lined us up in sitting positions on the football field and walked the lines, asking us one by one what we wanted to do with our lives. I became steadily more panicked as she started down my line, wondering what I would say in my poor English. My heart was beating so fast I thought I would have a heart attack. Eventually she came to me and asked me the same question and I managed to say "I want to be a guide" because nothing else came to mind. "How sweet", she exclaimed. So I began girl guide training in my spare time. I was taught how to pitch tents, basic wilderness survival, tracking, and other skills. I was also given a special knife that had different tools folded into the handle, similar to a Swiss Offiziersmesser. Before long on, this knife would save me from a dangerous situation.

Life at College was organised and disciplined. Its pseudo-military principles extended into our daily lives. The expectation that we should keep our quarters clean and tidy was enforced through routine inspections by the principal. She would give us a few days' warning before arranging for a visit to our rooms. On the first such occasion I cleaned my room thoroughly, and when she arrived she did appear impressed with my efforts, until near the end when she approached the table lamp on my desk, which was quite striking: a pumpkin gold flourishes on it that looked like Arabic calligraphy. As she asked where I had received such a beautiful lamp she ran her finger on it and it came away covered in dust. The lamp was the only thing I had forgotten to clean, mistaking the dust for the actual colour. I was embarrassed. Then the principal noticed that there were large patches on my wall where the lime had been picked away. I explained that I had developed a strange obsession with picking and eating the lime on my walls. It had been going on for some time and I could not stop, I told her. I had made quite a map on it. The principal was concerned that this indicated that I had some underlying disease.

We talked a little longer and I confided in her that while I could write English fairly well, speaking was difficult for me. She advised me to practise reading English out aloud. I didn't mention to her that my Urdu was quite bad also. Once I had said to the khansama, "hum pani khayenge" and he replied, "bibiji aap pani khayenge aur roti piyenge". My inability to master Urdu frustrated me. I expressed this in English class one day when we were given four words with which to construct a sentence. One of the words was 'language' so I wrote 'I hate Urdu language'. The teacher was a Pakistani Urdu speaker, but rather than being offended, she gave me full marks. I have forgotten her name but remember to this day her graciousness.

I had cultivated good relationships with the staff, and one day when a fellow East Pakistani student named Satera Kashem was planning to visit Bangladesh, she asked for my help: she needed a large metal trunk and wanted to borrow the khansama's. He was an old man who was understandably possessive of his property. Eventually, after much lobbying by Setara he said that he would let her have it if I vouched for her. I did so as Setara swore she would bring it back. However, Setara left and never returned and the old man never got his trunk back. This incident pains me to this day, as back then I was too thoughtless to replace it for him.

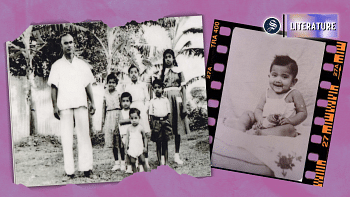

My camaraderie with the staff was a double-edged sword. When my eldest uncle Shamsuzzaman, a chief engineer at Chittagong Port Trust came to see me at Lahore, he introduced himself at the visiting room and eventually found his way to me. Upon seeing me he berated me because the staff seemed to know me quite well. To him this indicated that I was badly behaved. I remember little else from that visit. His admonishment overshadowed the joy of seeing a member of my extended family in a foreign place. This uncle of mine was tragically killed by the West Pakistani army six years later, during the night of March 25, 1971, when the invading army targeted the intellectual backbone of East Pakistan.

I discovered a Chinese restaurant near the college and began to frequent it, always alone. I would order the fried rice, vegetables and chicken and take the leftovers back to the hostel. They would take a long time to serve the food. The different accoutrements of the dining experience would arrive in increments of half hour; first the plates, then the knife and fork, finally the food. During this period I would get increasingly impatient and hungry, so when the food finally arrived it would taste delicious no matter what the quality. I once tried a soup at this restaurant after seeing it on the menu. When it tasted strange I asked the waiter what it was made of and he said lizard's tale. I expect he was joking.

Even though I had a generous stipend, I often ate on credit at the hostel canteen. This was only because I was too lazy to carry money with me. My dues at the canteen built up to an alarming amount but for some reason I kept avoiding settling the bill. So one day I ventured there in full niqab and ordered a number of things to eat. I paid for the food but only for that day. The manager saw me and may have suspected that I was the girl with the delinquent account. I was anxious but said nothing the whole time. He drifted close to me several times but in the end seemed to lose his nerve and walked away.

Communication continued to be a problem for me in Lahore. I greatly wished to become a better speaker of Urdu and English, but I found it difficult to motivate myself to master these two languages. This inertia was overcome one day when I was lying on my bed during the day and overheard two girls fighting in English in loud voices in the verandah. The hairs on my arm stood up. I was astounded that such a gulf in linguistic abilities could exist between three non-natives speakers of the same language, where two of them could argue in a language while the other struggled to even get a sentence out. I vowed then and there to master English at a level of proficiency so that I too could one day quarrel in that language.

My English skills were poor in part because of my father's frequent transfers. They not only interrupted my education but also led me to studying preponderantly in village schools that had Bangla as the medium of instruction. As a result, among other academic deficiencies, I spoke English poorly. But thanks to my father's supplementary efforts on that front I was still leagues ahead of the other East Pakistani girls at the college, who, upon discovering my relative facility with the language, would call on me to write their English reports and take me with them to the shops to speak to the shopkeepers. I had only a few stock phrases such as "show me this one" or "show me that one" but this was enough to suit their needs. Since I was a junior student they felt comfortable ordering me about.

While I was shy about speaking English and Urdu given my lack of ability in both, I nonetheless sang loudly and shamelessly while playing the harmonium I had brought with me from Dhaka. I had minimal interactions with the other girls because of the language barrier, so my harmonium became my best friend. Even though the songs I sang were classical, I overheard some girls sneer and say that I was from a "baiji" family. In the sixties women who sang and danced were looked down upon in West Pakistan.

The rewaz that I was so particular about would begin nightly at ten pm and continue for at least an hour. One night I was halfway through one of my sessions when Zahera, the African girl next door, yelled out: "Rosy we are sleeping. Please sing quietly or practice in the morning." I was outraged to be so interrupted. I fumed for some time as I translated my rage into (what I thought were) the appropriate English words: "Look. This is my room. This is not your father's room. I will sing a hundred times if I want to."

Zahera, who had much better manners than me, simply said: "Rosy, I said 'please'." I don't recall if I granted her request to spare them my singing the remainder of the night, but the general incivility and rudeness I displayed with Zahera was typical of my behaviour in Lahore.

Despite these fractious encounters with the students, the teachers were amused by my naivete and lack of inhibition. They would often call me into their chambers if they ran into me roaming about in the courtyard and sometimes ask me to sing. One song I remember singing on those occasions was 'Bachelor Boy' by Cliff Richards, but whether the lyrics were in Urdu or English, they were tinged by a strong Bangla accent.

The teachers at the college ate very well. Sometimes when the bearers carrying their lunches and dinners passed me by I would peek under the covered dishes. Although I was often tempted I could never muster up the courage to taste these dishes. I saw that one teacher fond of coconut was getting slivers of it with her food. Another, Ms. Doshi, was kind enough to share her lunch with me on occasion. She was tall, heavy set and dusky-skinned. She had a lot of achar with her food and it was only the achar that she would share rather than the other food which looked more appetising.

I ate a lot considering I was only 5' 2" and 90 pounds. I could grab a hold of my waist with my two hands. The other girls measured my figure and they came out to be 32-20-30–very thin but the girls still envied my figure and thought I was shapely. As I would leisurely walk down the driveway to join the boys, the girls would call out to me: "figure nikla ke nikla ke kaha jati ho?" They thought me bolder than all of them and when I would go out of the campus with male students they would betray their curiosity, asking how I felt sitting with the boys. Whether I felt shy, etc. As always, I told them the truth, which was that I felt nothing.

Actually, the truth was more nuanced: when I sat with the boys I just felt like one of them, or I felt that they were like me. Perhaps the boys were more confident of their charm, for if there were any films or programs that involved East Pakistani culture, the Bengali boys from the other colleges and universities would come and convince the principal that I should go and experience it so as to stay connected to my culture. We would take packed taxis where I was the only girl sitting with all the boys in tight quarters.

These extra-curricular activities meant I found time for everything but my studies. My marks were strictly mediocre, but even though I hardly spent any time studying I was never branded as a bad student. I didn't find the subjects hard, rather I found them uninteresting. My attitude was that I had not come to Lahore to study but to get away from my grandparents. At that time I subscribed to magical thinking where I could stay back in Lahore even if I failed all my courses. Even when Shamsul Haque, who had been on my interview board for the scholarship, came visiting the college one day, I complained to him that I didn't like the subjects that I had to study at this college and if he could transfer me to another. He laughed and said that this was not possible.

My neglect of my studies caught up with me, as I soon discovered when I was late on returning to the college after attending a cinema screening. The principal informed me that I would be under detention at the college for the next few weeks, a period in which I was not allowed to leave the campus for any reason. I didn't mind the punishment. Rather, I worried more about the program I had planned for the next week with the boys. I stunned the principal by asking if my punishment could be postponed for a week so that I could still go out with my male friends. Shocked by my audacity, she muttered something about East Pakistani girls to the other teachers present.

Unlike East Pakistan, West Pakistan had TV broadcasts. The local TV station in Lahore at the time was promoting East Pakistani culture and would invite a number of us East Pakistani students to sing Bangla songs at the studio. This became a fortnightly routine for us. Along with the East Pakistani boys I would go to the TV station and sing songs live on television, the only girl in the group. The TV producer, Mr Aslam Azhar, would ask us to sing Tagore songs but we would sing random modern songs instead and claim that they were Tagore's, figuring the audience and the producers wouldn't know the difference. Thankfully, they didn't. Instead, they paid us handsomely: 44 rupees per person per appearance, and the next morning my picture would be in the dailies. I regret that I didn't save a single one of these news clips.

I had no one in Lahore to look after me. I was all by myself in a foreign city, and mostly fine with it. I would watch the relatives, loved ones and local guardians of the other students visit, bring food. Once a student's grandmother brought mustard saag for her, which she later ate with great relish. Apparently, this was a delicacy in West Pakistan, even though back home it was considered the food of the poor.

Other students would receive carrot achar from home, which I found went very well with chapati and meat curry. I began to ask for it from the other girls during my meals. The achar was simple: just slices of carrot soaked in vinegar, sugar and salt, but it tasted wonderful. We could also get excellent seekh kabab and naan for just one anna at the hostel. The meat was cooked in a unique way, where it had the appearance of looking raw even though it was perfectly cooked. I don't know how they did it. When we sat at the table a teacher always came and joined us–one for each table–to ensure that we were following proper dining etiquette and not wasting food.

During Ramadan the menus changed. Paratha and keema or some other meat was served during sehri. Fasting was compulsory. We had to rise every night for sehri and finish the meal no later than 5 AM. Absolutely no food was served during the day, until iftar. Under such draconian circumstances, I somehow managed to observe my fasts for the first few days, but soon found it impossible to continue. I would find ways and means of getting around fasting. So, during sehri I began wearing pants with large pockets, into which I would abduct extra parathas from the meal. These I would consume in private during the day, in a private place where I would not be spotted. I assessed that the bathrooms were the safest place for this sinful act. This is how I survived my first and only Ramadan at the college. This situation has not improved with time, as I still find it very difficult to fast, even though I understand that it is meant to be a challenge. During Ramadan I would think back to my maternal grandfather, who would tutor me while fasting and when restless with hunger, rise from his desk to pace back and forth, muttering to himself about whether anyone would beat him with a stick if he broke his fast secretly and ate some food. Perhaps I inherited his mentality.

For iftar during that month we were served milk with rosewater which I found quite delicious, and gulab jamun served as dessert. When some girls didn't want or didn't finish their portions they would give it to me and I would accept happily. I rarely ate any food that was good for me, but retained the fondness for grapes that I had developed back in Dhaka. When I discovered that they were cheap in Pakistan I gave 2 taka to the khansama to buy me some. He brought back an enormous amount, far too much for one person. I nonetheless put in a heroic effort to finish them all in one night and as a result had an upset stomach the next day.

I would eat anything that tasted good. Dairy products such as chhana, ghee and doi (yoghurt) were everyday food for us growing up. And even during my childhood my parents would nag that I didn't have a healthy diet, that I should eat more vegetables. I never listened, perhaps because my eating didn't appear to affect my figure. No matter how much I ate I stayed thin.

During one holiday my friend Setara and I were out in the bazaar in Lahore and met a Bengali family. We were excited to find countrymen, and when they offered us to stay at their house we agreed. It was a good fortune, we thought, as the college was closing for the holidays and we needed a place to stay. We followed the address to the edge of town and after an uneventful dinner retired to our rooms. Mine was on the first floor and overlooked a patio. There were two beds in the room and I took the one closest to the door. Later that night, I woke up with a start when I felt a hand on my neck. I began yelling that there was a robber in the house, trying to snatch my necklace. I called for the man whose house we were in, referring to him as 'uncle'. I didn't realise that it was his hand that had been on my neck. My yelling had shocked him in the dark room. He ran out to the verandah and pretended that it was my shouting that had woken him and that he was there to investigate. He asked me where the thief was and I said that he had just been there, putting his hand on my necklace.

I left the next morning. Setara, unaware of the depredations of my host, stayed behind. I returned to the college to see if I could stay there, but they were closed for the next few days, so I had little choice but to return to the home of the attempted rapist. I hired a taxi to take me back to the house, which I remembered to be on Ferozepur Road. However, I was no longer certain of the exact address. We drove along the road several times in vain hope of finding the house. The taxi driver was getting impatient as a great dust storm was brewing on the horizon and he was eager to get away. He was unconcerned about leaving me in the middle of it.

I finally asked to be let off at a spot that seemed somewhat familiar, thinking I could find the house by walking around on my own. The light was fading fast. The wind was rising so dust was everywhere. The shops were pulling down their shutters. I needed help, so I found the oldest, kindest-looking shopkeeper I could and asked him in Urdu if he would take me to the house I was looking for, giving him a general description. He agreed and we set off down the road. We had been walking for only a little while when he grabbed my hand and told me I would have to come with him. Thankfully, I had the girl's guide knife with me. I took it out of my vanity bag, held it toward the man and told him that if he didn't put one mile between us I would stab him with it. The man ran away begging for his life, referring me to as bibji.

I kept walking through the dust and darkness, more and more lost. I saw no one in the howling sands. Everyone else had taken shelter. The storm eventually stopped, but by then I had completely lost my bearing. I walked for hours, not finding the house, my legs getting cramped and numb, my surroundings growing increasingly more desolate. The houses were farther and farther between until I crossed an empty stretch of road with nothing but empty fields and jungle on both sides. I saw a group of men sitting around a big fire they had built in an oil drum. They were bare-chested and scary looking, their glowing faces intent on the fire. I kept walking and they didn't notice me. Now that I think back on it, they may have been dhobis.

A car began following me, creeping behind slowly, I don't know for how long. When I walked it would follow. When I stopped it would as well. I went to the window and asked the driver why he was following me. He tried to persuade me to get in his car, assuring me that he had no one at home other than his aunt and that I would be safe and comfortable there. I told him that he was welcome to help me but only if he came on foot. My experiences over the last day had shaken the naivete out of me. When he refused I told him to leave. I kept walking. He crept behind me for a while longer before finally turning around.

Around midnight I saw a large gate with lights above the two columns and ran toward it, and when I saw the sign declaring it to be the Punjab University Girls' Hostel I wanted to cry with relief. I woke the security guard and told them all that had happened. The man fetched the superintendent and I repeated the events of the day to her. She asked me where I wanted to go and I asked her to send me to Punjab University. She said that they would be happy to help me as long as I left the knife in their care. The following day I would be taken to Punjab University, she promised.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments