‘It feels like a living thing’: The House on RK Mission Road

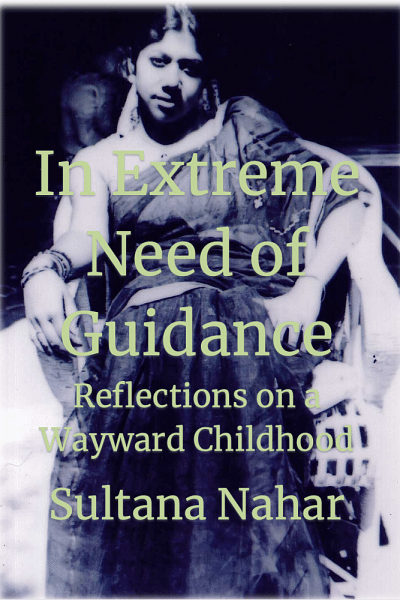

My mother has enjoyed a long and successful career as an author, publishing everything from books of poetry to scholarly studies on the treatment of minorities in Bangladesh. Yet the one thing she never considered writing was a memoir (specifically, one about her youth) until I badgered her into it. In Extreme Need of Guidance, the book being serialised here, captures the first sixteen years of her life, so wild and rich with experience that my entire existence seems dull in comparison. 'The House on RK Mission Road' is the first chapter of this memoir.

These stories from my mother's youth make me laugh, a lot. I am honoured to have played a small role in bringing this work into the world.

- Arif Anwar, author of The Storm

*

THE HOUSE ON RK MISSION ROAD

The first home my parents lived in was on Ram Krishna (RK) Mission Road in Old Dhaka, where it still stands. It was gifted to my parents by my paternal grandfather upon their marriage. The building has been extended upon and renovated since then, but at that time, just around Partition, it was a modest two-storey home with high ceilings and thick walls that kept the interior cool during the summer. Now, it is the only single home still standing on the street, all others since been converted to tall apartment blocks.

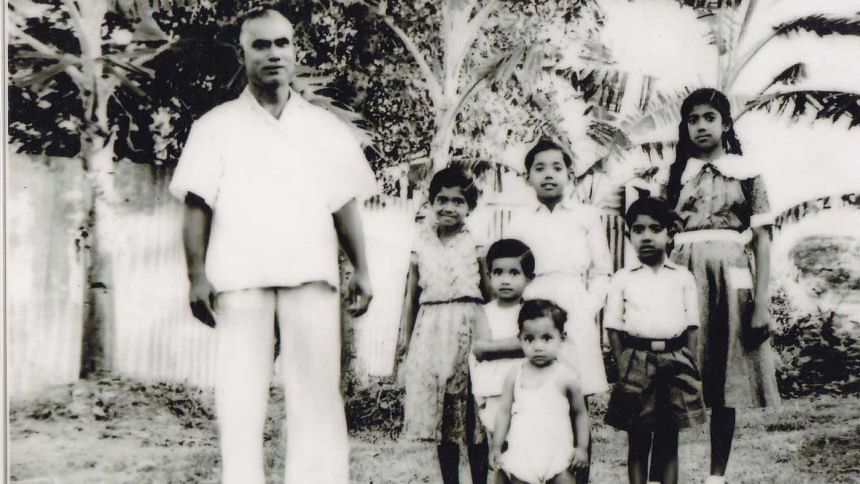

My parents had nine children, of whom I am the eldest. Our feet, and those of our children and their children have pressed on the cool cement of the house on RK Mission Road. Many mouths have tasted the rose apples from the tree that stands in the courtyard. When I think of the thick limestone walls of the house now I think of the essence of the generations of our family that it has absorbed. The house feels like a living thing.

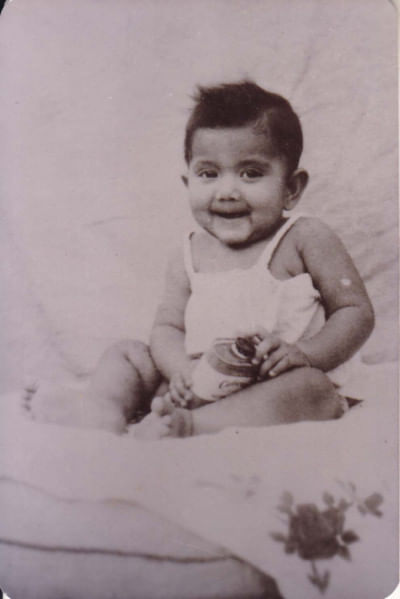

I was born exactly at 11 PM on July 19, 1948 at Mitford Hospital in Dhaka. It was soon after Partition, and some British doctors and administrators had remained in the country to continue the transition of the hospital's operations to local hands. The hospital had a good reputation overall, but reserved their best service for the British and other Europeans living in Dhaka at that time. My mama (uncle, or mother's brother) was a magistrate at the time, and he pulled strings to have my mother, Shamsunnahar Begum, admitted to the hospital when she was close to her date of delivery. She was given a cabin that was normally reserved for those of European descent, or for natives who were Very Important Persons. My mother was sixteen. I would be her first-born child.

The English obstetrician was astonished to see a (in her eyes) tiny girl about to give birth. She and my mother did not have a language in common, so the doctor would regularly peek in with just her head and offer an elongated kemoooooon whenever she came to see my mother.

I was considered a heavy child at 8 pounds, and unattractive enough to send my mother into a temporary whirlpool of depression, so distressed was she to be somehow involved in my arrival to this world. But these feelings gave way to motherly ones soon enough—when I grew older, she told me that I was born the same year as Prince Charles of Britain, and was four months his elder.

My father, a police inspector stationed in Dhaka, was very excited about the birth, spending much of his modest salary to hire two nurses to look after my mother. One of these nurses would come to our home on Mission Road once my mother was released from the hospital a week following my birth.

The quality of care that my mother received at Mitford, the gleaming cabin and the excellent food, would stay with her the rest of her life. Alas, given the nomadic existence that my family would experience following my birth, none of my mother's remaining eight deliveries would match up to the experience of her first.

In keeping with the culture of the time, no one would have been surprised had my father been disappointed with a first-born girl. Thankfully, he was excited to have a child regardless of gender. He bought so many sweets to celebrate my birth that a horse cart had to be hired to deliver it all. I received a very expensive and smart looking pram of khaki canvas cloth, but much like my mother's hospital stay, this extravagance was also limited to only my birth. None of my father's subsequent issues would be greeted with such fanfare.

Our home was large enough that my family decided to host live-in guests. This was not only done as an additional source of income, but also because my parents saw this was a communal service. They paid a modest amount a month and had their own quarters but we would dine together. My mother would serve them as they ate. This was expected of her as a hostess. On occasion they would make special requests of her in terms of the dishes served.

The gentlemen we hosted were well-educated and on the path to future prosperity and/or renown. I remember four clearly: Mr. Rashid-uz-Zaman who was then a Reader at Dhaka University. Dr. Lutfur Rahman who would later become a CSP Officer, Mr. Mazumdar who worked for British Tobacco. And Mr. Awal, who managed a textile mill.

One-time Mr. Awal's mother sent for him from the countryside some aam shotto (mango fruit leather). A great delicacy. Upon receiving the package Mr. Awal handed it to my mother with a request to store it and to give him some when he asked for it. He was planning to have it with milk from time to time. My mother put it on a high shelf in the kitchen but I soon found the jar and began to pilfer from it on a regular basis until one day I finished all of it.

Eventually Mr. Awal remembered his mother's gift and asked my mother to serve some with his meal. My mother went to the kitchen and discovered what had happened. Embarrassed, she returned and told Mr. Awal that her daughter, Rosy, had eaten all of it. I don't remember the extent of Mr. Awal's irritation but he said something to the effect of one mother sent it and another mother has eaten it.

Another time, when I was a little older, say seven or eight, I was wandering aimlessly through our backyard when I came across Mr. Rahman, who was by the well we had at the back of our house. He was shirtless and had a small pot of oil with him; he was planning to take a bath. Seeing me, he said, "Mother, would you mind putting some oil on my back?"

The request gave me pause. A latent sense of propriety reared up in me. The task seemed simple enough but a small voice in me insisted that it would not be proper for me to fulfil this request. So I said let me ask my mother first. At this Mr. Rehman quickly declined my help with thanks.

Dr. Rashid-Uz-Zaman on the other hand liked to quiz me on my studies. One evening he asked me to compose an essay about Dhaka. I began with the line: "Dhaka is situated on the banks of the Buriganga river." He read the essay and commended me on my work. I didn't tell him that I had copied the essay line by line from my textbook.

Our house was located in Old Dhaka, where there were a number of stately manors and zamindar houses. One had a beautiful rose garden and a menagerie of birds such as ostriches, peacocks and swans. In the late afternoon we would go there to play as it allowed for the neighbourhood children to enter and browse the gardens.

Nearby this rose garden was another called 'Sadhur Bagan'. It had a large pond in one corner. Bathing there one day I lost a gold ring of mine. My father was understandably very angry with me and beat me. Later I returned with a colander and strained the mud for days but never found the ring.

I came to this same pond one morning to find it overflowing from heavy rains the previous night. The water covered the green grass. A large catfish had become stranded on the ground. It was mature and light coloured and alternated between struggling on the ground and staying still, as though conserving energy. I ran home to fetch a copper bucket and returned to find the fish still there. I held the bucket close to its head and flicked water at it as I was afraid of touching it. It crawled dutifully in and I ran back home to show it to my mother. She was happy to see the night's dinner in the bucket and cooked the fish with the stalks of daata shaak. This was a relief in those days as my mother was frequently in a conundrum as to what to cook on my father's meagre salary.

Given the crowded house, my most cherished time was early in the morning, when I was often the only one awake. When I was six or seven I developed a passion for collecting flowers at dawn. My chosen spot for collecting them was beneath the shefali tree in our neighbour's front yard as they normally left their gates open early in the morning. I would gather up the flowers and later in the day thread them into garlands.

On one such occasion I woke up thinking it was near dawn. As usual no one else in the house was awake. I opened the deadbolt on the bedroom door standing on the bedposts to reach it, which I recall had a sun motif on them. When I stepped out to our verandah I didn't notice that it was much darker than expected. I went outside to the neighbour's front gate and found it closed. So I took the narrow passage that ran between our houses that led to their outhouse, which like the outhouses of most middle-class families were built on concrete pillars, and climbing up from the bottom I gained access to their backyard. Taking this circuitous path I eventually made it to their front yard to find that not a single flower was on the ground, and roaming the grounds was a frightfully large monitor lizard.

The front gates of most houses then were narrow and wooden, since cars were very rare, so despite being a small child, I was able to open the deadbolt easily and run out. Returning to our house, however, I saw a great, massive black dog sitting in our front yard with its head between its paws. The hair on its body was long. It was so large that when it sat up its head reached the second storey of our house.

My screams drew my family to the front yard, where they found me shivering with fear. I told them what I had done, and seen. They checked the time and saw that it was two in the morning. My mother heated salt on a spatula and made me take it to calm me—a village remedy for those badly frightened by the supernatural.

The experience of the dog in our front yard, despite its immense size, was not a dream. Of this I was convinced, even though my dreams at that age were unusually vivid, full of wonder and mystery. In many of them, I could fly, often around the house, or more memorably in a dark, empty temple with soaring ceilings, its walls crowded and bulging with carved figures. In another I was in a strange city, flitting around giant humming structures the size of buildings, made of shining steel. I had the sense that they were immensely powerful and arcane machinery of some kind, with great moving gears, pistons and unknown mechanisms moving upon their surface. In my dreams they would hover far above the ground and were extremely loud, but I had no clue as to their true purpose.

Returning to the matter of the flower picking: my childhood was defined by such unruly and aberrant behaviour. Biris held a particular fascination for me. Whenever I would spy an unfinished one on the ground I would immediately put it in my mouth and try to smoke it. One day, having spotted one on the floor of our verandah, I was about to pick it up when my father came up from behind me and grabbed me by the back of my neck. He asked me what I was doing. He had been watching me for some time. I thought quickly and told him that I was simply keeping the house clean by picking up trash. "The servants keep throwing biris on the ground," I said.

He caught me like this many times. Another time it was when I used the epithet shala. He asked me to repeat what I had just said and once again I was able to think quickly. I said I was simply saying 'sala', a near homonym that means 'burlap sack'.

I was always looking for things of interest on the ground. One day I had an incredible bit of luck and found a one anna coin in the house. I ran to the shop immediately to buy lozenges with this substantial sum of money. I asked the shopkeeper for one anna worth of lozenges and he placed eight on my palm, but when I searched for the coin to pay him I could not find it. I had put it in the elastic band of my trousers, but it must have fallen out while I was running to the shop. I returned the candy and returned home greatly disappointed.

I was involved in all manner of neighbourhood sports and games, and especially enjoyed playing marbles with other children, who were often the young servants of other households. These games would take place by the side of the road and involved hitting marbles from a distance with your own. Whichever marbles you hit became yours. Passersby would often stop to watch us play. One time, a European man walking past us stopped to watch us play and after a particularly good strike by me exclaimed, very good in English.

One of these marble sessions ended badly as one day my maternal uncle, returning from classes at medical college, caught me playing with the servants—an unforgivable act. He took me home, threw all my marbles in the well and struck me with a length of firewood until my knees bled. These beatings from my near relatives were frequent occurrences in my childhood. My mother did not have the nerve to stop them, but later, with a sad face but no words of comfort in her mouth, she would bathe and clean my wounds.

All manner of street food merchants hawked their wares on the streets where I played marbles. When my mother handed me six paisa one day to spend at the grocer's, I found my opportunity to taste these wares. I saw that a man was selling serbet—coloured drinks of many hues attractively packaged in long-necked bottles. I sat down at the table and requested a drink from the yellow bottle, having forgotten all about the coriander my mother had sent me out to buy. When the drink was set before me in the heavy, green-tinted glass, I took a big sip and found it less delicious than I had imagined. I got up and began to walk away, making a terse comment that the drink was not tasty, the six paisa clutched tightly in my hand. Seeing me leave, the serbet wallah said, "Khuki, paisa?"

Yelling that a kidnapper was after me, I ran home without looking back. My father had just returned from the office. He was in uniform and held a leather baton in his hand. I told him that a child snatcher (considered a great menace in those days) was following me. My father was understandably very concerned and accompanied me to the sherbet wallah's cart. When he inquired to the man as to what had happened he said, "Sir, I only said, 'khuki, paisa?'"

My father wanted to then pay the man for the drink but he refused. I am not sure if I was later beaten for this incident.

I am certain that my frequent beatings at the hand of my father (my mother was the only adult in the family who did not beat me) had an effect that manifested itself in other ways. For example, I would frequently wet the bed. I would be dreaming that I was urinating in the bathroom only to wake and find that I had done the deed in the real world. My invariable strategy upon discovering this was to stack all the pillows I could find over the offending area of the bed and flee the scene.

This bed-wetting wasn't confined to our house. When visiting relatives in Kaliganj once again I wet the bed and employed my trusted pillow strategy. However, when I was standing in the kitchen my auntie shooed me away, complaining that I smelled like pee. I kept wetting the bed until the age of 10.

My father was a gazetted officer respectably placed in the police. He had a limited income and never took bribes. Such scruples, uncommon at the time, meant a meanness in our upbringing. We ate simple foods and my siblings and I always wanted for new clothes. I remember that once my mother sewed me new knickers with a print of red flowers on a white background. This was underclothing but I was desperate to show it off to the world. I eventually found a way: I stood before our main gate and faced the road. Then, as if I had collected rocks on the lap of my frock, lifted it up so that my underwear was visible to the passersby. I held the pose for a few minutes and once satisfied that enough people had seen my new underwear, went inside. I was about four or five.

As I grew older and our family became slightly more affluent, I became more possessive about the clothes I wore. There was a tailor our family frequented and I warned him that he must keep exclusive any design work he did on my clothes, barring that he would have to stitch the words Rosy Frock onto the dresses of any girls who wore a design identical to mine. But the tailor would break his solemn compact with me, for I soon saw a neighbourhood girl wearing the same frock as mine. I pretended to play tag with her and smeared amlaki juice on her nice new frock. Amlaki stains are permanent.

When I was a child, adults would invariably ask children one of three questions, all of which I found irritating. The first involved a child's roll number–adults always wanted to know my roll number, which I was reluctant to reveal as it was quite high. The other was what their mother had cooked that day or would be cooking that day. This question I would answer by inventing a list of fantasy dishes to hide the actual simple dishes that my mother was making that day, but I would get them mixed up and the dishes would sound increasingly nonsensical, for example: catfish and beef curry, rice pudding made with lentils, etc. The final question or demand from adults to children would be to translate a sentence from Bangla to English. I don't remember how I did with these questions but I suspect poorly.

My distaste for any activity related to education, or studying, began early. In 1954, when I was six, my father came from the office with a gentleman in tow. At that time he was working for the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) in Dhaka. I was not yet attending school. My father informed us that this gentleman was to be my private tutor.

Upon hearing this news I went to the bedroom, crawled under the bed and started crying loudly. For a long time no one could get me out. Even when someone was able to finally extract me from under the bed I ran to the neighbour's house to crawl under one of theirs. When my father sent his nephew to fetch me, our neighbours began berating him because they thought I must have been beaten very badly to cry so hard. My cousin then explained to them what had happened.

Nothing I did could keep the teacher from visiting our home every day. This familiarity and routine didn't change my attitude. In fact, matters became so severe that my mother resorted to drastic measures: when it was time for the teacher to visit, she would take me to the front room and tie my hands with a rope that she attached to the desk leg. She would then quickly leave the room as she was a purdah observing woman and did not wish to be in the same room as a man who was not her husband. The teacher would arrive and leisurely untie me so our lessons could begin. Through all this, I wept with outrage.

Some weeks passed. My teacher tried to mollify me with the occasional sweet, melting my heart but a little. In that time I had realised that I could lift up the desk leg and slip off the rope. I was able to do so once or twice before my mother began tying me to the window grill. It was dawning on my family that I would never be academically distinguished.

Unlike my studies, I was diligent about music. This pleased my father, a music lover. Anyone expressing interest in music had his unstinting support. When my mother revealed an interest in learning to sing he immediately bought her a harmonium and appointed a music teacher to provide her with lessons. She quickly became a decent singer and in turn taught me.

Unfortunately, while my father was a music lover, he was quite strict about the lessons, and would beat me if I made a single mistake. While singing before him, I would always be nervous about an incoming blow. I would make errors, stammer and stay stuck on a single word in fear of a blow. But thanks to him and my mother, by the age of six I could both sing and play the harmonium. In time I also learned the tabla and practised it with great devotion. I sang loudly at night and fell asleep with my harmonium on my bed.

Early morning rewaz was very much in vogue at that time, especially in the Hindu households. Conventional knowledge claimed that it was critical to keeping one's voice in tune and improving vocal range. There was an informal rivalry in the neighbourhood as to who could rise the earliest and begin singing. This is why I would rise before dawn and sing at the top of my lungs, my voice blaring out into the neighbourhood. The mornings when my voice was the first to infiltrate the neighbourhood the girls in the others homes would hurriedly rise and begin their own singing. The mahalla would pulse with our duelling, disparate harmonies.

The mornings when I was the first to begin singing were counted as a victory, and the ones when I failed to be the first lent a bitter taste to the remainder of my day, and I would vow to rise even earlier the next day. This zealousness about rewaz would cause problems later during my time at the Home Economics College in Lahore, which I will recount shortly.

Once music and breakfast were done, in my pre-school years, I would head out to play immediately. A V-shaped wall separated us from our neighbours at RK Mission Road. I would climb up on this wall and run around on it all day. Sometimes a girl named Khaleda who lived in the neighbourhood would join me and we would spend the whole day on the ramparts. Thick green moss clung to their tops, leaving us comfortable cushions, sitting on them, Khaleda and I would wonder if we could spend our whole lives up there.

We could spy on our neighbours from these walls. One of these households, our next door neighbour, was quite wealthy. Whenever I heard the clitter and clatter of utensils I knew that if I sat on the wall I would see them devouring delicacies far beyond our modest means. It seemed the matron of the family would eat her food with great relish, nodding and sighing in appreciation as she ate. Watching this, my mouth would water and I would swallow hard. I began to discuss these things with my mother—who sometimes acted like an older sister given the small gap in our ages. When I raised this topic with her she excitedly claimed that the rich ate such good foods that they defecated in very tiny amounts, as little of the nutrition was wasted by the body. Their shit is like the tiny droppings of a goat, my mother said.

I became obsessed with eating like the rich. Having heard of steak, I once fried a piece of meat in butter on a pan, all the while thinking to myself this is what wealth smells like. I would dream of buttered toast and jam, which to me was the height of luxury eating. In comparison, our breakfast was usually chapati, alu bhaji and sometimes sattu. On special occasions some ghee and sugar might be sprinkled on the chapatti. This was a delicious and rich breakfast, but I couldn't bring myself to appreciate it at the time.

At one point my father and my eldest maternal uncle decided to rent a large house together. We shared the rent and split the cost of the groceries. My aunt came from a wealthy and haughty family and she forbade her children from mixing with me and my siblings. I was curious about my cousins and one of the questions I asked them concerned what they ate for breakfast. They confirmed that their food was similar to that of our rich neighbours. It must be very tasty, those foods, I said to them and they said yes before being called away by my aunt. I had proof of my cousin's claim one morning when I watched from the doorway as my aunt put butter and jam on a whole stack of toast right in front of me. Once done, she closed the door on my face without offering me a single slice. I was no more than five, I don't remember my exact sentiments from that time, but I recall not being happy.

Read Chapter 2 of this memoir on February 18 on Star Literature.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments