Displaced in Dystopia

Photo: Kazi Tahsin Agaz Apurbo

Shahzadi Begum sat on her bed, her eyes firmly on the recording device set before her. She wore a smile across her face, belying the apprehension evident in her eyes. "When they were asking people if they wanted to go to Pakistan, I wanted to go too. It sounded like such a wonderful place," Shahzadi responds when asked about the repatriation decision. "I don't anymore. I have lived in this country for so many years; everything I know is here," she adds, a sudden blush streaking across her face. Shahzadi Begum moved to Geneva Camp, one of the largest camps housing the so-called "Stranded Pakistanis" located in the heart of the capital city, with her husband. A people persecuted ever since independence, Shahzadi's story is all too similar to the thousands of others who also call this little place in their city their home. While our current discourse has often attempted to alienate these individuals, to be forgotten in the recesses of history, a landmark verdict granted them citizenship back in 2008 bringing them to the fleeting national consciousness. Since then, much has changed but perhaps not enough to make a marked difference.

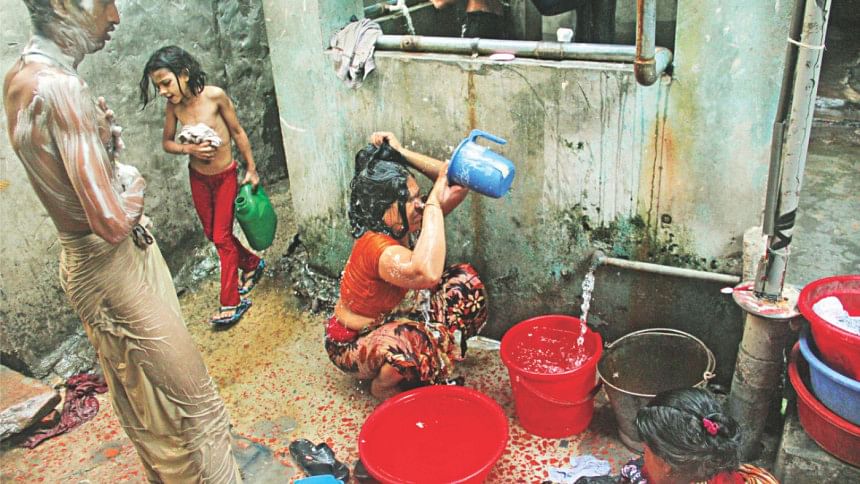

Shahzadi Begum's husband worked in the railway industry; a common profession of choice for those who had migrated here from Bihar, an Indian state known for the same industry. However, before she arrived in the camp, Shahzadi used to live in the city. She cannot recollect the name of her previous area of residence, but she has happy memories of the time there living with her parents. After moving to Geneva Camp, Shahzadi saw a drastic change in her living conditions. The small room where she sits now has a large bed, a wardrobe shelf with a small 24" TV on top and some cooking utensils. This small room happens to also be her entire house. "My husband bought this for us a few years after our marriage," Shahzadi remarks, beaming. The pride she has can be seen in the house itself; it is as clean as can be, perfectly juxtaposed against the environment outside. "I have no complaints," Shahzadi says before mentioning the difficulty she has in using the communal toilets, having to stand in line for hours. Apart from that, she doesn't have much to say. It may also be because she doesn't want to say much. She seems content, almost happy, in this place of hers, where there is just about enough for everybody but not a lot for anyone.

The sultry afternoon heat, coupled with a sudden power outage, finally convinces Shahzadi to go outside. She sits on her doorsteps, just like others around her, each doorstep featuring one individual plucked on top, engaging in conversations with their neighbours. The sense of community here is unmistakable. For a people so long persecuted, their unity makes almost a tragic sense. When many among them finally wish to stake out in the greater world on their own, it is a decision celebrated. Even though it is extremely difficult for those who have lived here to rent homes outside, the Geneva Camp address working purely as a deterrent for many landlords, there have been a few who have managed quite well to be accepted by the mainstream Bangali society. However, no one stays away for too long. Mohammad Hussain*, a former resident of the Geneva Camp, recalls his days here quite fondly. "This is where I grew up so of course I have deep roots. For instance, every weekend I bring my mother back here so she can meet everybody and they can all gossip," Hussain says. The camaraderie is best exemplified by the manner in which people greet Hussain, all seemingly elated to see him back and curious about his life outside the invisible prison of forged identities.

Mohammad Hussain himself is a shining example of how far the community has come and where it is headed next. The evidence of the change in generational dimension can be seen everywhere. While Hindi or Urdu can be heard, Bangla too isn't a surprise. And while some of the previous residents may have nurtured hopes to return to the Nation of Islam, the current generation shares no such affinity with a foreign nation. "We are Bangladeshis and we deserve the same recognition," Hussain reaffirms. The current generation has successfully made the transition and now hopes the same for all their peers, but again their loyalty to their roots remain. "We love our country and we love our community so much so that when one of us dies, the body is brought back here so everyone they ever knew or loved could pay them their final respect," Hussain informs.

A sudden burst of cheers is heard above the cacophony of voices. A wicket has fallen in the ongoing cricket match. It seems one house has power only and the others have gathered at the doorstep to watch the match. Someone brings over a pitcher of water and everyone has a gulp. With little resources, much is shared. The discussion halts as everyone returns to watching the game. Some watch further away from the others; class politics is one that no community can shake off easily, it seemed.

The Bangladeshis in Geneva Camp though have begun to shake off the stigma attached to their past. As they progress further, their integration will be soothed. But before that they will all fully comprehend what this nation tried to do to them. They will fully understand why they were deprived of the right to vote, to educate themselves, to even go to the doctor, and to simply live like humans. But whatever the case, they will not forget the place they have called home for the last 45 years or so. Perhaps it is time to kick-start the debate not on rehabilitation but on reconstruction. The country gave them a cage and they turned it into a sign of their defiance and resilience. Should we now force them out of the cage as well? Or should we let the Shahzadis and Hussain's pen their own journey, as we have let them do so, ever since we began to say we were independent?

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments