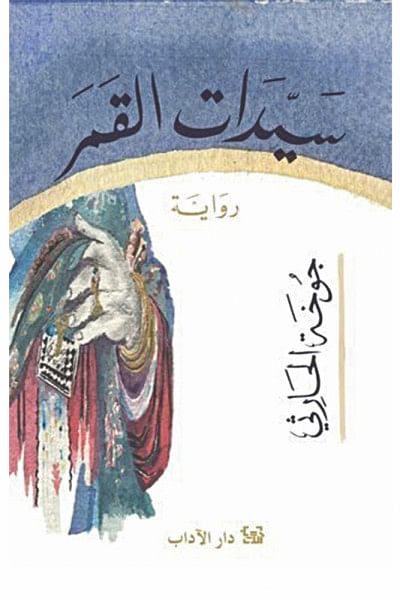

Jokha Alharthi's 'Celestial Bodies': More than a glimpse into a culture

Celestial Bodies (Catapult, 2019) is the kind of novel you hesitate to call "historical". It's entirely too personal. Recalling the time of his father's death, when he had to bathe his father's corpse, the character Abdallah says, "Some years later, other details enter this picture. I'll see my father's belly tremble slightly under the bucket of cold water. The water will form a small pool, and this pond seeps out to trickle through all the alleys of al-Awafi." The lines reflect the essence of what author Jokha Alharthi accomplishes with this 2019 Man Booker International Prize-winning book, translated to English by Marilyn Booth.

The story focuses on the loves and lives of three sisters, Mayya, Asma, and Khawla, but meanders into the memories of other characters peopling their lives—from ancestors to husbands to slaves to neighbours to daughters. Each chapter is fleeting and inked in delicate, gossamer-fine prose, told alternately from the perspective of each character. But just like the pools that drip from Abdallah's home into the longer al-Awafi alleys, these insightful, heartfelt snippets capture the lived experience of an Oman in transition over decades—from the country's history with slavery until 1970 to the Treaty of al-Sib, which granted Oman autonomy in 1920; from days when education even for little boys was a rarity, to the boom and bust of a modern real estate market in the 20th century.

Personally, I was skeptical of Western media's praise that the book offers a "fascinating glimpse" into a rarely-seen culture. It makes the novel sound didactic, as if Alharthi were trying to initiate a Western audience into the Omani lifestyle. Nowhere in the book does Alharthi attempt to decode or explain the book's setting to a potential outsider. Instead, from the very first line— "Mayya, forever immersed in her Singer sewing machine, seemed lost to the outside world"—we're planted firmly in the minds of the Omani characters. We watch their lives unfold through a kind of portrayal that seems to say, this is just how things are.

In the very first chapter, for instance, Salima, the girls' mother, recalls her first time in labour. Shaykh Masoud's daughter gave birth lying down? The shame! The weakness! Salima had stood straight holding on to a pole, holding back her screams, until baby Mayya had popped out into her baggy pants.

Later in the book, we watch as Asma finds her philosophical footing through sparring rounds of poetry with her father, as Mayya uses her enforced marriage to wedge into a modern Muscat, and as Khawla awaits an old lover who leaves and returns to her, storm-tossed by his financial failures in Canada. We watch other lives that live in margins and the in-between places: Zarifa, a slave and mistress but more than a mother to Abdallah, her master's son; Abdallah's mother, believed to be killed by a jinn, but in reality, possibly poisoned; Salima, an orphan in her uncle's home growing up hungry and lonely, accepted neither as part of the family nor in the frivolity of the slaves; and Masouda, mangled and gone mad from overwork, locked up by her daughter in a threshing room, forever screaming, "I am Masouda! I am Masouda and I'm in here…"

That these women's narratives are told in third person reflects the imprisonment they suffer at the hands of a deep-seated patriarchy in their society. But the strength of their convictions and beliefs—innocent, courageous, vicious—prod at the limits lined by the third-person narrative. A silence blankets their lives. It always has. But you also hear the cacophony of thoughts and secret pains and joys ringing within them, because this style of storytelling captures both the power possessed by these women as well as the powers that suppress them.

In comparison, the only character who commands the first-person tense in his chapters is Abdallah, Mayya's husband. As the only man whose story weaves through those of the women, he gets to narrate his life himself. His gender allows him that privilege. Yet his is the most vulnerable retelling, the most haunted and traumatised and linguistically experimental. In the space of the same paragraph and often the same sentence, Abdallah reveals the abuse he faced as a son, the rejection as a husband, the misery of watching a daughter suffer in love, all at the same time. We flit from pain to pain at a dizzying speed in his flashbacks: "Get me out of this well, Father. I won't be longing for those magpies and I won't play ball with the boys. I won't stay up late listening to the bewitching melodies of Suwayd's oud. I won't scream into your face, and you in a coma. I won't leave Zarifa, your beloved, your mother, your daughter, your slave, your lady." "But my father still shouted at me, calling me boy. I was the father of three children, I was no boy," he says of his deceased father.

These stories are all glimpses, yes. But it's akin to peeking into the drawing rooms of families and discovering their complex and painful secrets, the places where the paint has chipped off. They're too potent to be thought of merely as nuggets from a culture. By removing the barrier of quotation marks, by rendering the shifts in time and space as smooth as sweeping sands, author Alharthi and her translator Marilyn Booth submerge us entirely into the lives of these Omanis. Lives that are weaved with and exist within the religious, political, and socio-cultural realities of their surroundings, complete with the way they eat, the way they celebrate weddings, the way they prepare for childbirth and exorcisms and deaths. Here, history isn't remembered as "history", trickling down from textbooks and news reports into etched out characters. It is remembered as a fresh wound.

Sarah Anjum Bari is Editor of Daily Star Books. Reach her at [email protected] and @wordsinteal on Twitter and Instagram.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments