Silencing the past

At a talk by Pakistani-American Professor Sara Suleri, author of Meatless Days, I listened to an eloquent rendition of the role played by Pakistani feminists against the oppressive policies of the former military dictator Zia-ul-Haq. Dr Suleri beautifully outlined the repressions under his rule that relegated women to the four walls of the home, thus reaffirming their domestic role as central to an Islamic ideal.

As the awe-struck audience, mostly North Americans and students from South Asia, listened to her arguments, I felt deeply uncomfortable with what remained unsaid. When the session opened for Q&A, the audience showered praises on the work of Pakistani feminists. I did not question their brave work, but I knew that Dr Suleri had erased a key aspect of Pakistan's feminist history. Raising my hand, I said, "Dr Suleri, you presented skilfully the formidable challenges faced by Pakistani feminists in resisting Zia's repressive rule. But could you please enlighten us about the role played by Pakistani feminists during the 1971 war in former East Pakistan, now Bangladesh, when hundreds of thousands of Bengali and indigenous women were raped by the Pakistan military?" Dr Suleri, who had moments earlier basked in the warmth of her audience, faltered visibly, and paced back and forth on the podium acknowledging the validity of my question. After a few minutes, she said that it was a difficult time for feminists and requires further reflection.

As the audience dispersed, a young Pakistani male graduate student approached me. "What is this about rape you mentioned?" I explained that in 1971, West Pakistani feminists had not only failed to acknowledge the atrocities committed by the military in Bangladesh, but certain prominent Pakistani feminists attended the United Nations to deny any atrocities by the military. Taken aback, he said that such events were entirely absent from his education.

I recommended that he visit the library to read international newspapers about the 1971 war in Bangladesh. Several days later, I received an email from him thanking me. "There is a total news blackout on 1971 in our history books. I hope to visit Bangladesh one day and ask for forgiveness for what was done in our name."

What do we risk when we silence the past? Haitian anthropologist and historian Michel-Rolph Trouillot, in his seminal work Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History, provides an excellent framework for understanding how histories are constructed, how certain viewpoints are magnified, while others are sent to the 'dustbin of history'. Not only does power shape historical production, but silences are also purposefully baked into the recording of history. His framework resonates with the political landscapes of Bangladesh in 1971 and in 2025. If history is replete with elaborate omissions and distortions, how can a lay person make sense of it?

Silencing 1971

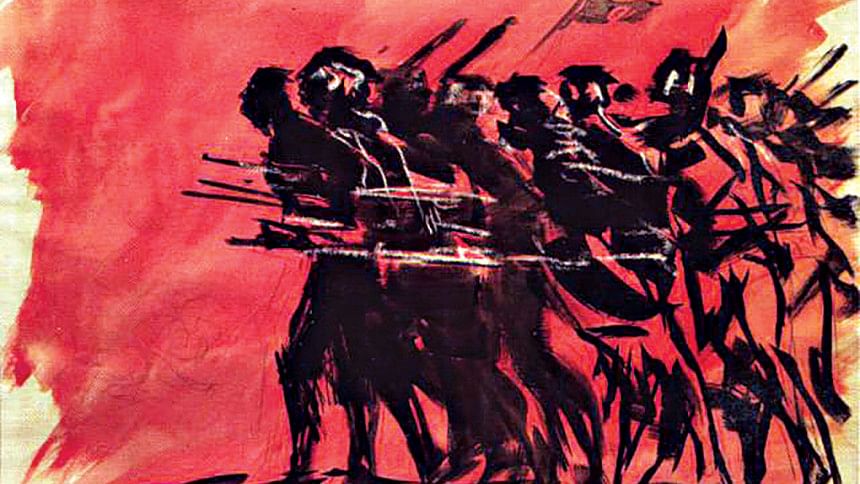

The Liberation War of 1971 saw ordinary Bangladeshis rise against the brutal atrocities committed by the Pakistan military. The Mukti Bahini was a People's Army made up of students, teachers, politicians, civil servants, small businesspeople, rickshaw-pullers, farmers, women—in other words, people from all walks of society. However, once in power in 1972, the Awami League wrote a partisan history, recasting them as the heroes.

Similarly, the role of women in the liberation struggle is largely seen through the lens of victimhood, focusing on rape as a weapon of war. While this crime against humanity must never be forgotten, it also obscures the multifaceted contributions of women in the Liberation War. Women fought on the frontlines alongside men, helped run freedom fighter camps, and played various critical roles in the war effort. Why, then, have they been sidelined in history?

I do not recall the exact year, but it was possibly in 2011–2012, that I attended a gathering of female freedom fighters organised at Gonoshasthya Kendro in Savar. It was the first time that their sacrifices were acknowledged publicly. Many of the Hindu freedom fighters had relocated to West Bengal, so fellow fighters were meeting after almost 30 years. The women laughed in joy while telling the audience about their experiences of 1971. The most moving moment came when each was given a flower as a tribute to their patriotism. Thanking the organisers, one of them said, "This is the first time I have been recognised as a freedom fighter. No one ever thanked me, let alone gave me a flower." Their erasure from the historical narrative underscores how often women's contributions are relegated to the margins.

These historical silences extend beyond the war itself. The plight of the stranded Biharis, confined to camps since 1972, remains a glaring omission in Bangladesh's national history. Many of these individuals, born after 1971, bear the stigma of their parents' and grandparents' allegiance to Pakistan. Although finally granted citizenship, their futures remain uncertain due to long-term state indifference. Similarly, the indigenous communities of Bangladesh, particularly of the Chittagong Hill Tracts, and their struggle for autonomy and recognition have been excluded from the dominant history. These omissions reflect Trouillot's argument: history is written by those in power to serve their interests, systematically silencing inconvenient truths to consolidate authority.

The August Uprising

Fast forward to 5 August 2024, when a popular uprising overthrew the Awami League government in Bangladesh. But in the events unfolding five months after 5 August 2024, I see a troubling parallel with the historiographical silences surrounding 1971. Led by students but soon joined by people from all walks of life, the movement challenged the fascism of the Awami League government under Sheikh Hasina and forced her into exile. Watching student leaders expound their historical ideas on media, I realised many had grown up with a fragmentary history manipulated by political agendas. It is not their fault, but the fault of an education system where textbooks present a patchwork of propaganda—Awami League triumphalism, military revisionism, and partisan agendas—leaving little room for historical fact-checking.

Among the demands arising from a certain student segment is the call to send the 1972 Constitution to the graveyard, and to write a new constitution. The 1972 Constitution is a document marred by many amendments designed to consolidate an undemocratic authoritarian rule. But if the Constitution is sent to the graveyard of history, what will replace it? Who will write the new constitution, and under what legal framework? The Constitution, to be acceptable in a democracy, must be passed into law by the elected representatives of the people. How will that occur if the Constitution must be symbolically killed, written afresh before democratic elections? The demand here escapes the rules of parliamentary norms. Reforms must be made for a fair and free election, but beyond that, constitutional recommendations should be debated in an elected parliament.

Some compare the Liberation War of 1971 to the Popular Uprising of 2024. In 1971, Bangladeshis fought the Pakistani military for nine months; millions were killed or maimed, women raped, babies bayoneted, and intellectuals murdered. It was one of the most heinous wars of the 20th century and must never be forgotten. Yet the promised freedom remained unfulfilled. 1990 offered a second chance—and again, we failed. Political parties have repeatedly failed the nation, fuelling the youth's anger and distrust. Can these parties be trusted, or will they merely change colour? Perhaps new parties are needed to ensure accountability.

In 2025, Bangladesh stands at a crossroads, grappling with the weight of its unfinished liberation project. The youth's desire for a tabula rasa—a clean slate—is understandable, but history is never a blank page. History is a palimpsest formed through the struggles, sacrifices, and aspirations layered into it. Karl Marx's maxim that history repeats itself, "first as tragedy, then as farce," is a sobering reminder of where we are now. Bangladesh's journey from 1971 to 2025 is marked by a series of unfinished revolutions, each promising democracy, freedoms, and justice, yet falling short every time.

The current moment demands more than grandstanding; it requires a commitment to genuine democratic reform. Parliamentary elections must be held, and the interim government must outline a clear path to democracy, balancing the urgency of the present with the lessons of the past. But seven months is too short a time for the interim government to solve the debris that has accumulated over the years. The interim government must align with political parties, student and people's groups to bring all voices to the table. Similarly, the now bickering groups must set aside their differences to work with the interim government to renew the democratic project. In reclaiming our history, we must confront the brutal silences of the past. The question is not merely who writes the next chapter, but how lessons are learned, so we do not go down the wrong road once again.

Dr Lamia Karim is a Professor of Anthropology at the University of Oregon in Eugene, United States.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments