A novice’s sadhusongo

In the early 2000's, a concept restaurant was opened in my birth-town, Paris, France, named "In the Dark" ("Dans le Noir"). Clients enter a completely dark space, and are served a set menu which, obviously, they cannot see. I have never been to this restaurant. But when I think back on the first time I came to Bangladesh in early 2016, springs to mind what I imagine a dinner at "In the Dark". As a yoga teacher and lifelong spiritual seeker, I had come to Bangladesh compelled by curiosity: I wanted to see a sadhusongo. There was no set plan, only the contact of a contact in Dhaka, and a strong belief in luck (or fate, however one may choose to call it). Through some online research and after watching a video produced by UNESCO, I knew these were festivities organised by members of the lineage of the world-famous spiritual master Lalon of Cheuriya (Kushtia), which tend to last 24 hours, take place in remote villages, and include music and food. Little was I prepared for what I was about to witness, and the subsequent upheaval it provoked in my life.

I was accompanied by a close friend of mine, Olivier Remualdo, who took the pictures that illustrate this article. Both Olivier and I had spent extensive time in South Asia, him as a professional photographer, me as a sadhak and academic researcher. As most Western city-dwellers who have previously visited the sub-continent, we were expecting sensory overload, and a chaotic loss of personal space and privacy, even possibly agency. The godlike importance of hospitality is not specific to the region, nor does it generally entail being taken on as the host's own -- guests tend to remain foreigners, however well they may be welcome. As we embarked on a bus from Dhaka to a village of which we didn't know the name, let alone the location on a map, I absolutely had no idea that I was about to find a place I could truly call home. I have referenced "In the Dark", as I then did not understand Bengali, and participating in an intimate sadhusongo in a small village at the border with India relying only on sensorial observation, empathy and intuition was a profound experience that I will try to summon up here. I understand that the society which has subsequently embraced me, and the festivities to which I now regularly take part, are as foreign to some Bangladeshis as it was to me then. May this article be as interesting to the reader as if I was inviting them to this concept restaurant – the degree being different, of course.

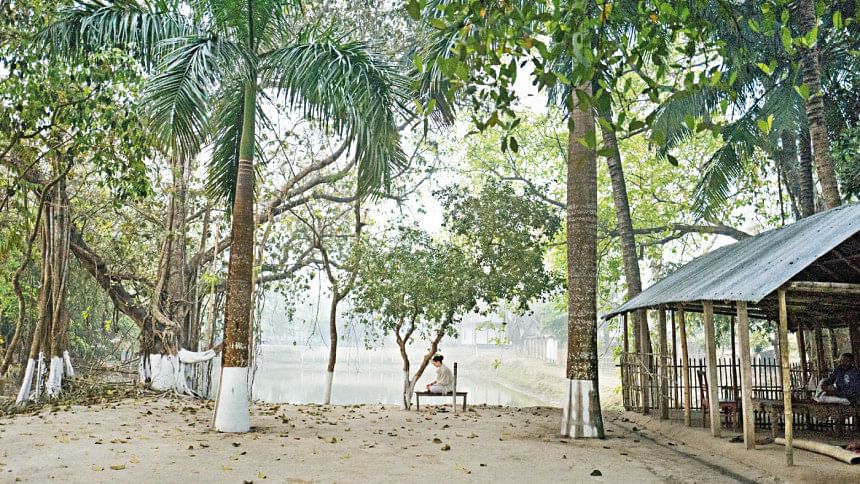

Most living beings rely on their senses to organise their surroundings, and give meaning to the world and their own life within it. The sensory overload that can be felt in the villages in Kushtia is firstly provoked by the vigorous relationship to the elements: the strong presence of water and the ever-blowing wind, the use of woodfire to cook, the intense smell of the earth and the exuberant vegetation, in which so many insects and birds find shelter. Our first night on that sadhusongo adventure was spent at Hem Ashram, the akhra of the sadhu who is now my guru, Fakir Nahir Shah. Razon Fakir, one of his close disciples, who became my husband in 2017, cooked rice with reverence on an earthen stove outside, under an overarching sky lit both by myriad stars and fireflies. The feeling of peace and wonder, of having finally reached home, did not require any language. Looks and smiles were enough.

We made for the sadhusongo the next morning, on a "pakhi van". The sight of the fields filled with fully-grown tobacco plants, and the smell of smoke as they are being processed by hand in small adobe houses, induced an even deeper sensorial release. We were greeted by Fakir Mohorom Shah, the sadhu who was organising the sadhusongo, on the occasion of his wife's death anniversary. After a short walk on a narrow dirt path raised between two ponds, we were seated in a large makeshift tent, in which other members of the congregation were already settled. Within a few moments, everyone was called to sit in line, as a group of disciples started organising the washing of hands and plates, and the distribution of the lunch dishes, rice, vegetable curry and lentil soup. Thick incense smoke was passed in heavy earthen holders to sanctify the meal, one plate after another. The sadhus gave a short benediction, then started eating, and so did we.

No one will doubt the stark difference in taste, in emotion and in intention between commercial food and home-made food. But as I was to understand later, in this community food is prepared as devotion. The acts of cooking and eating are entirely turned towards the inner God, an offering to this deep mysterious presence within the heart of human beings. And so, the food is not tasted as it is cooked, nor is it consumed until it reaches the plate of the sadhus, very much as "prasad" is offered in temples all over the sub-continent. In sadhusongos, the taste that can be felt on the tongue, the smell of the food, as nice as it may be, is not nearly as satisfying as the deep taste that awakens within the soul. Having spent time in yoga ashrams in Europe and India, I had read about these concepts, the philosophy of this type of cooking and taking food. As a long-term vegetarian, I was already convinced that in the sustenance department, we should eat to stay alive, healthily and happily, rather than live to eat. However, this lunch was my very first direct experience of what is called "seba", or "devotional service", as it can be related to food. The deep experience of "seba" was renewed as many times as we were served food. Two traditional meals even now summon up strong sensorial memories pertaining to that very first time I tasted them: jhal muri in the evening, rice pops mixed with fresh cilantro, thinly cut green chilli and mustard oil; and the breakfast of chira, or rice porridge, with banana ripened on the tree and homemade hyperlocal fresh cow's milk yogurt.

Sadhusongos are strange occurrences. People from all walks of life temporarily leave their worries behind, and join together in a time-space beyond ordinary time and space. Some off-times were also offered at different times during the event, which gave me an opportunity to try my hand at turning chappattis (rotis), and take short walks around the village. The attraction of two foreigners in this remote village did not allow for any time alone, and rather than fight the current, I chose to "go with the flow". I started listening more closely to the rhythm of Bengali, which I was finding particularly pleasing. For some reason, Bengali reminded me of Spanish. As I later dedicated myself to learn the language, I was able to understand Spanish and Bengali grammar do have some common points. But for the time-being, children and women would point at different items around us, and enunciate the Bengali word, sometimes even remembering the English translation. As a very independent-minded self-relying Western city-dweller accustomed to solitude, the sheer concentration of population was both exhilarating and tiring. Many people in the villages never get to meet a foreigner, and their spontaneous curiosity led to some laughs, as well as some unease. One occurrence of the latter was waking up from a short nap and being met by the face of a woman staring at me from a few inches. One occurrence of the former was being dressed up in a white saree in the fashion of the fakiranis by one of the aunties, and the shape of my lean, sporty body prompting awkward looks and probes, which I dispelled by some jesting. Smile is an international currency that does not require any knowledge of economics.

The path of the Baul-Fakirs of Bengal is often described as "humanism". But it not only places the human being at the centre of life. It has also displaced most of the region's religious practices, to refocus them on special humans who, as a result of their spiritual application and the grace of their guru and lineage, have developed the qualities that liberate humanity from its instinctive nature. According to the core teachings of the Baul-Fakirs, a list of qualities – named the ten directions, to echo the ten directions of the world, in a microcosm-macrocosm mirror-play typical of esoteric lineages – are to be acquired by the disciples for them to be considered religiously accomplished. Another two sets of three concepts complete the injunction. The final set, namely faith, unity and discipline, crowns the previous thirteen aspects. They imply that personal achievements and social participation are, again, different scales imbricated like old-fashioned Russian nested dolls. As the different chapters of the event unfold, mainly through music, discussions, devotional prostrations, offerings and the sharing of meals, these three qualities are embodied, and revealed.

I remember being particularly mesmerised by the songs of devotion after the evening prostrations, sung as one voice, highlighted only by the clapping of hands. The only words I could understand then, which were repeated time and again, were "guru" and "Lalon"… but the atmosphere that was created still resonates in my heart every time I now join my voice to the group. Not speaking the language, not having previous knowledge of the culture, led me to feel these three qualities, unity, discipline and faith, particularly strongly. The last musical moment of the event, in the early afternoon of the second day, which culminated in what could be called ecstatic dance as flower petals were showered in an atmosphere heavy with incense smoke, made me feel as if we were all cells of the same being, each with their own path and responsibility, each as vital as the other. I guess most people who label themselves as "humanists" like to say that they believe we are all one. The category who prefers pointing fingers would say the human race is only divided because of politics, greed and egotism. The more spiritual type will quote ignorance, fear and confusion. In a sadhusongo, or on a larger scale, in the society of sadhus, simplicity is a keyword, that enables very different people to share what can be described as the most basic aspects of the human life, creating this simple joy of being together. To reach this state beyond language, beyond culture, beyond discomfort, was for me a turning point. It lifted up a veil, and revealed a space deep within that I had merely glimpsed from afar. A peaceful sense of gratitude was made present, and I held on to it dearly.

After the event, we went back to Hem Ashram. And a crazy decision starting to emerge from deep within: I had to engage in this path. I had to partake in these three qualities. Whatever the cost. And this oath I took with myself then, in February 2016, still carries me to this day, through the good and the bad, through trials tougher than I could ever have imagined, and moments of joy more intense than I thought I had the strength to bear. Here and abroad, people inevitably ask me what I possibly could have gained by leaving my luxurious life in beautiful Paris, to settle in conservative countryside Bangladesh. I usually suggest they ask me what I have lost. And the answer is, everything that can weigh down a human being longing not for unreined freedom, but for inner liberation. Paraphrasing Nietzsche, "it takes chaos to birth a dancing star". Or in other words, it is "In the Dark" that light is created.

Deborah Zannat is a Baul-Fakir disciple , Lalon Shah's lineage.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments