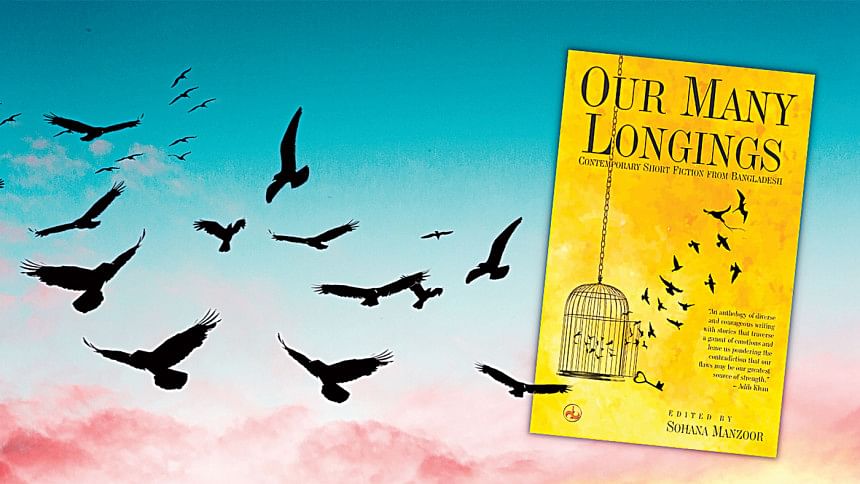

Diversity and nuance mark the Bangladeshi experience in Sohana Manzoor's 'Our Many Longings: Contemporary Short Fiction From Bangladesh'

So many words have been used to describe this nation in the last 50 years. Started from a bottomless basket, and along the way we've been called resilient, passionate, corrupt, greedy, full of warmth. "Precocious" is a personal favourite—it is the adjective that always comes to mind when I think about my city and my country, a word I used to describe Golden: Bangladesh at 50 (UPL, 2021), one of the other short story anthologies on Bangladesh published this year. In The Demoness: Best Bangladeshi Short Stories, 1971-2021 (Aleph Book Company, 2021) and When The Mango Tree Blossomed (Nymphea Publications, 2021), critic, translator and academic Dr Niaz Zaman takes the more holistic route of curating a vast collection of stories that each reflect a different class, culture, temperament, and generational experience of being Bangladeshi. In Our Many Longings: Contemporary Short Fiction From Bangladesh (Dhauli Books, 2021), editor, translator, and academic Dr Sohana Manzoor settles on yet another emotion that so accurately describes what it feels like to be Bangladeshi. In 19 short stories, the book's authors and translators remind us of how, and how so very deeply, we long for things.

What do we long for?

Freedom. Kindness. Justice. Acceptance. In Farah Ghuznavi's "First Love, Second Chances", childhood memories and mothball fragrances of young love sit alongside the grace and clarity brought about by adulthood. I once asked the author, half in jest and half in fear, how she chanced upon this story in her mind, so real does it feel to anyone who has experienced meaningful connections in their life. Fayeza Hasanat's "Frank and Frida" plays with a similar lightness of tone as it revisits life altering encounters. But it goes a step further with its nods to how Bangladeshi women are made to be exotic in the Western world and are mixed up carelessly with women from India. If the dissection of this Western gaze feels less than precise, this is made up for by the author's trick in the climax—she reminds us gently, but with a tinge of mischief, that the lines dividing characters, protagonists, and narrators are etched as though on sand.

Have we achieved all that we longed for?

The grimmer stories in the anthology remind us of the ways in which independence has not touched individual lives and communities in Bangladesh. Afsan Chowdhury's "Torso", translated from Bangla by Professor Shamsad Mortuza, revisits moments of independence bestowed and denied—at the very moment that it was being fought for—due to the most intimate and physical of factors separating Hindus from Muslims. Years later, in Hasan Azizul Huq's "Without A Name, Without a Tribe", Rifat Munim translates from Bangla the ghosts and skeletons left behind by such violence.

Life has been kinder to Sultan Ahmed, the protagonist in Shaheen Akhtar's "The Green Passport", translated by Professor Arifa Ghani Rahman; kinder than it was to Sultan's Dada, who identifies as a "stranded Pakistani" and still mourns for his homeland Chhapra, for the son he lost in the war. Resentment for Bengalis is ripe among the Bihari family making up this story. "Underneath that country's smooth skin lies an open wound, pus, blood, and tears", they reiterate. Yet the Bangladeshi passport—an object we seldom associate with freedom or privilege these days—is a contested talisman of trauma and agency for the characters of this story.

In her introduction to the collection, Sohana Manzoor addresses the divides between stories written in Bangla and English, or the stories written by Bangladesh-based and diaspora authors of Bangladeshi fiction. Her motivation for curating this anthology was to "take stock [of] and bridge" some of these gaps. Choosing our collective state of longing as the unifying thread is an elegant and compassionate approach in itself; but I especially admire that the divides are deliberately made to seem inconsequential in the way that the stories were curated—stories of love and friendship resting alongside wartime trauma; stories of marginalized or expatriate lives resting alongside those set in the homeland or a majority community.

Personally, I enjoyed reading most of the stories in this book because they revel in the joys of storytelling and the empathy and whimsy it can inspire. This, coming from some of the major Bangladeshi authors writing and translating today—Professors Kaiser Haq, Fakrul Alam, Razia Sultana Khan, Syed Manzoorul Islam, Kazi Anis Ahmed, Khademul Islam, Tahmima Anam, and more—is a privilege to experience.

I enjoyed reading this book because it alludes to the nuance and the contradictions that mark the thousands and thousands of lives who have identified with or been marked by the Bangladeshi experience, which is something that often gets outweighed by the significance of the Liberation War. But it is people and their ability to care that makes up this country. In her short story, "Mother's Milk", Tahmima Anam spells out this sentiment most poignantly: "[Y]ou are pressing the buttons on your phone, or you are stirring the milk into your tea, or someone has tapped you on the shoulder, and the sorrows of the whole world, the woman whose baby has died in the flames, the little boy with cigarette burns on his torso, become yours, yet although you see and smell and feel everything, the edge of your own sorrow isn't blunted, not for a small, bare fragment of a moment."

Sarah Anjum Bari is editor of Daily Star Books. Reach her at [email protected] or @wordsinteal on Instagram and Twitter.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments