‘Bare life’ and Partition

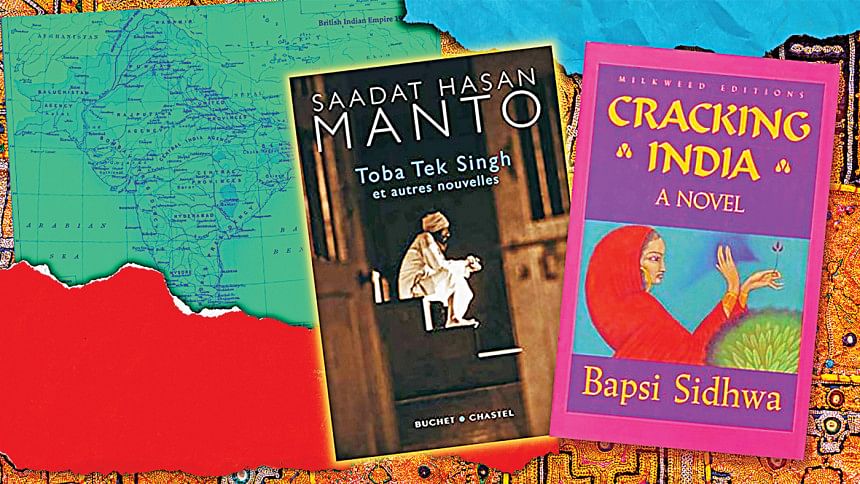

"Can one break a country...Will the earth bleed?" asks eight-year-old Lenny in Bapsi Sidhwa's Cracking India (1988)–a tale about Partition. "No one's going to break India. It's not made of glass!" Lenny's cousin retorts. However, the irony is that such musings cannot be brushed aside as mere childish naïveté. Their bewildered remarks convey an absurdity that indeed had characterised Partition. A similar absurdity is highlighted in Saadat Hasan Manto's short story, "Toba Tek Singh" (1955), which offers a satirical critique of the Partition.

This absurd historical event claimed one to two million lives—the earth did bleed. The Partition of 1947 was a "state of exception" in Giorgio Agamben's formulation: suspended as it was in a space in time where the laws that normally govern a state ceased to be effective. Agamben also distinguishes between 'zoē' a bare, de-politicised form of life, and 'bios', the politicised form of life in a society with its right to justice and law. This distinction is useful in understanding the depiction of women in Partition themed literary works, such as Sidhwa's Cracking India, and Manto's "Open it!" (1948) and "Cold Flesh" (1950). Although the female characters occupy the realm of de-politicised life in these texts and, thus, eventually become dead or living-dead, they continue to induce powerful effects in the living world.

Manto's short story "Open it!" narrates the macabre tale of a father and a daughter, Sirajuddin and Sakina respectively, fleeing a violence-ridden Amritsar amidst Partition. Sirajuddin loses Sakina and is ultimately reunited with her supposedly dead body. However, upon the doctor's nervous order to "open it [the window]" the lifeless hands of Sakina undoes the string of her shalwar and opens it. The reader is left to assume that the rescue team who found her, or perhaps the doctor, had repeatedly raped her so that the muscular movement involved in opening her shalwar has become a conditioned response to that order. Sakina lives in the zone of indistinction, the realm of non-political dead life—not just after her dead body is found, but throughout the whole story. This is because she is part of a discardable population which the state has "let die", as Michel Foucault might have put it: both as an exercise of its own sovereignty and for the greater good of the nation(s). After all, the nation was split into two partly to pacify the threatened sovereignty of two contending rulers.

That Sakina is a living-dead who has belonged to the realm of zoē all along is hinted at several times through ambiguous language and an eerie tone. For instance, after the rescuers/volunteers find her trudging along a field she turns "deathly pale" when they ask if she is Sakina—like the blanched pallor as she lay dead. This imparts a sense that she could have been dead when they found her in the field, but she also could have been living when they later found her "unconscious" rather than dead body. Moreover, the volunteers' words to Sirajuddin that "if his daughter was alive he would be reunited with her in a few days" is repeated, and even after the field scene the volunteers once again assure him that they will find her with no mention of having already met her–could she have been alive then when she would indeed be reunited with Sirajjudin? The reader cannot pinpoint where Sakina is alive and where dead and, in this manner, the line between the dead and the living is blurred to depict her in a perpetual state of zoē. However, even from the afterlife Sakina continues to create a range of changes in the living world through her conditioned response—it makes Sirajjudin ecstatic and, on the other hand, it makes the doctor break into "a cold sweat." Equally important, the non-living string gives a powerful testimony to what happened to Sakina in the living world.

Sidhwa's Cracking India narrates the horrors of Partition through the perspective of a precocious child, Lenny. Hers is a unique perspective because she is neither Hindu, Muslim, nor Sikh—she is Parsi, like Sidhwa herself. As Lenny's harmonious social world becomes rife with growing intra-communal tension that soon bursts into the bloodbath that accompanies Partition, a parallel change in her beloved, beautiful Ayah also occurs after she is abducted on account of her being Hindu. She is forcibly made a prostitute and raped. Consequently, the previously hypersexualised Ayah is portrayed with the mannerisms of a living dead post-Partition. Now, the "achingly lovely" Ayah who used to "inwardly glow" when she gazed at her lover, says "I'm not alive" to Lenny's grandmother when they meet after his murder and her abduction. Again, the line between the dead and the living is blurred as Masseur's (Ayah's lover) dead body is portrayed with life-like characteristics—"there was too much vigour about him still" in contrast to the deathly aura about Ayah.

After the political situation spirals into an exceptional state, Ayah begins resembling the non-political dead life that characterises the realm of zoē. Yet, she engenders powerful effects in the living world as in this moving passage. It occurs after Ayah has been brought to the rehabilitation centre for rescued women:

"And I [Lenny] chant: "Ayah! Ayah! Ayah! Ayah!" until my heart pounds with the chant and the children on the roof picking it up shout with all their heart: "Ayah! Ayah! Ayah! Ayah!" and our chant flows into the pulse of the women below, and the women on the roof, and they beat their breasts and cry: "Hai! Hai! Hai! Hai!" reflecting the history of their cumulative sorrows and the sorrows of their Muslim, Hindu, Shikh and Rajput great-grandmothers who burnt themselves alive rather than surrender their honor to the invading hordes besieging their ancestral fortresses."

Although a brief, blank look at them out of "glazed and unfeeling eyes" is the only reaction that the living-dead Ayah can muster, the moment she initiated is a demonstration in its own right, a merging together of female identities to conduct an act of resistance against the conditions that have made death preferable over life for these women. It is evocative of a previous scene in the novel when "A woman with a child on her lap slaps her forehead and begins to wail: "Hai! Hai!" The other women join her: "Hai! Hai!" Older women, beating their breasts like hollow drums, cry, "Never mind us…save the young girls! The children! Hai! Hai!" This is before Sikh mobs attack their village, and "rather than face the brutality of the mob" the women are to "pour kerosene around the house and burn themselves."

All in all, these texts delicately deal with the nature of bare, de-politicised life that characterises the state of exception into which Partition was plunged. The line between the dead and the living is constantly being blurred in Partition-themed literature and ultimately, the texts demonstrate that one can break a country; and that the earth also bleeds.

Syeda Fatema Rahman is an undergraduate student at the Department of English and Modern Languages, North South University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments