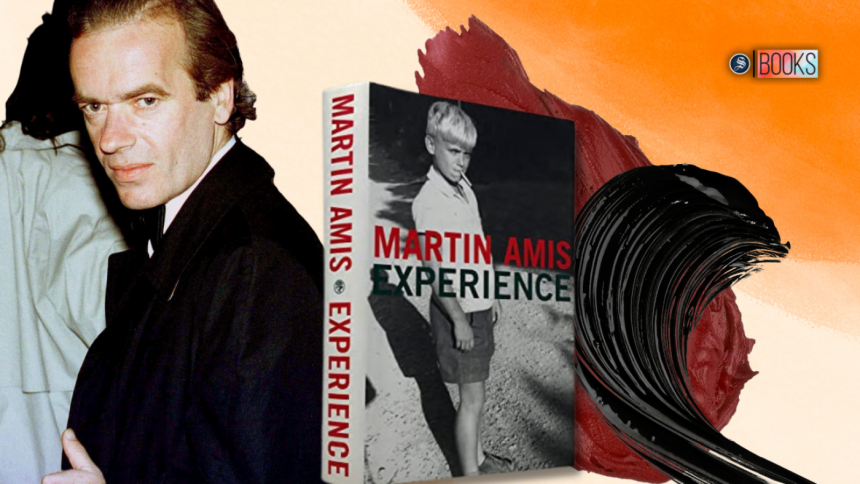

Like father, unlike son: Martin Amis’s place in literature

News of Martin Amis's recent death from cancer reminded me of the time I read a good portion of Experience (2000), his memoir, at the British Council library while waiting for a friend. Having been more of an admirer of his father's writing than his, I considered Amis to be the least profound of his generation, a cohort which comprised some of Britain's most celebrated writers of the 1980s. His contemporaries included Kazuo Ishiguro, who went on to win the Nobel Prize in 2017, Salman Rushdie, whose Midnight's Children clearly is among the best novels to be written post-World War II, and Ian McEwan, who has had a late-career surge with novels such as Nutshell (2016). The younger Amis's reputation, in contrast, seems to be still shaky.

Reading through Experience that day, I was left surprised at the casual rudeness:

My mouth talks too much. Only a week earlier my mouth had soured a New Yorker dinner at the Caprice in London by indulging in this 'exchange' with Salman Rushdie:

— So you like Beckett's prose, do you? You like Beckett's prose.

Having established earlier that he did like Beckett's prose, Salman neglected to answer.

— Okay. Quote me some. Oh I see. You can't.

Martin's final book, Inside Story (2020), billed as a novel though really it's a loosely drafted memoir, carries on, unfortunately, with the same smarmy tone that tries hiding the vapidness of his interactions and memories. His incessant need to address the "reader" drags on the patience of any actual reader. One almost sympathises with his father, who according to an anecdote, had once flung his son's book across the room when he discovered that Martin had used his own name for a character. For Kingsley Amis, this was akin to breaking a contract with the reader. There should be "no fooling around with reality." But fooling around with reality is somewhat of a specialty for Martin. His notable works succeed because he is so unbearable with it. It wouldn't be a good Martin Amis book without his narrators breaking the fourth-wall or playing around with some postmodern gimmick.

London Fields (1989), arguably his best work, is a glossy murder-mystery embossed with such a tone of meta-narrative fashionable of the '80s. Here, it is evident that Amis's charms (and inevitable obnoxiousness) is a result of his tiresome devotion to style (being as he was a major fanboy of Nabokov), aided by themes of glamour, celebrity, and debauchery, which the book is chock full of. In London Fields and its preceding novel Money (1984), Amis does imbue an anger, but it is a different sort of feeling, not the "Angry Young Men" humour of Lucky Jim or The Old Devils, novels which made his father's literary name. But rather there is a sense of boredom in Martin Amis's work. After a while, one gets the idea that Amis is hellbent on being a "disinterested aesthete". Nowhere is this more apparent than in his nonfiction work Koba the Dread, a "study" of Stalin's brutality, which reads hollow and impersonal, almost clinical.

Perhaps Martin Amis's works do not grab me for the most part because it veers too far away from the humanism of, say, Saul Bellow—a writer Martin greatly admires and has written about extensively. Where Kingsley Amis was often a much needed dose of angry wit, his son's anger came off as decadent, rebellious without much cause, and unnecessary to an extent. Martin's great literary achievement is that with a set of forgettable novels he was able to carve out his own place, away from his father's shadow. There is no doubt that he could write. He was by the age of 27 a literary editor of a major outlet and had been a part of the British scene ever since his childhood. But to what extent the intoxicating personality and the good looks will translate to a readership beyond his life is at best unanswerable. The odd Islamophobia and right-wing remarks do not, of course, help. What is certain however is that as a celebrity and intellectual, Martin Amis definitely has a place as 20th century literature's most remarkable and original nepo baby.

Shahriar Shaams has written & translated for SUSPECT, Third Lane, Six Seasons Review, Arts & Letters, and Jamini. Find him on twitter @shahriarshaams.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments