How Partition impacted the Dhaka book trade

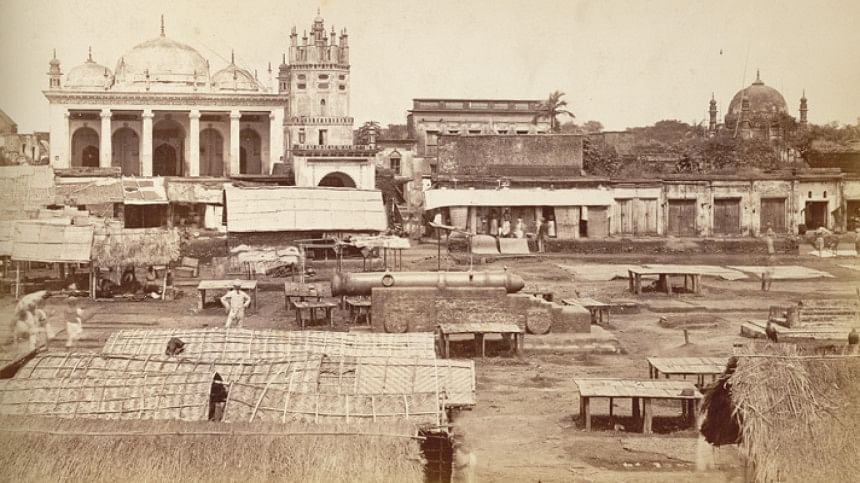

If you roam around Old Dhaka, you will come across multiple road names associated with Basaks such as Madan Mohan Basak Lane and Radhika Mohan Basak Lane. The Basaks were a sub-group of weavers who, according to HH Risely, turned to agriculture and other trades after the decline of cotton trade in East Bengal. In the pre-Partition period, the Basaks, along with Duttas and Dasses, were dominant figures in Dhaka's book business. After the Partition, many of them left Dhaka, and the vacuum was filled in by Muslim entrepreneurs. A significant number of these new Muslim book traders migrated from Kolkata. The impact of the Partition was felt in every aspect of Dhaka's printing and publishing business, and the book trade in the new provincial capital took a momentous turn. This article is an attempt at understanding this moment of rupture in Dhaka's book history.

Although the Kattra Press (c. 1849) was the first printing press in Dhaka, the Dacca News Press was the first to be run on commercial lines. The establishment of Bangala Yantra in 1860 by Broja Mohan Mitra is considered to be a watershed moment in Dhaka's printing history as it boosted the publication of Bangla books and newspapers in the district. Dinabandhu Mitra's famous work, Nil Darpan (1860), was published by this press. At that time, it stormed the colonial government and created a huge uproar in the social and literacy circle of Bengal.

Interestingly, there was a bookshop named Cheap Library in 1860. It is assumed that one of the Basaks was its owner.

The Bengal Library Catalogue shows that Dhaka's printing business expanded during the 1880s, and Hindu entrepreneurs owned the major share of this trade. During 1877-95, out of 45 presses in Dhaka only six were owned by Muslims and only two of these were in operation for any length of time: Mohammadi Yantra (1873-94) and Azizia (1876-90).

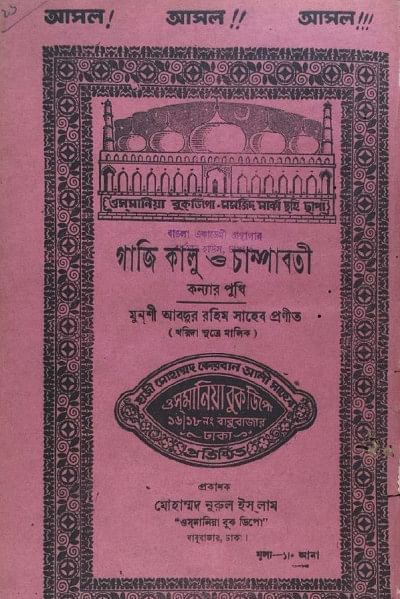

During the 1860s, a brisk trade of punthis developed in Chawkbazar's famous Ketab Patti. The publishers, traders and readers of these punthis were predominantly Muslims. According to Professor Abdul Qayyum, more than 100 Islamic punthi titles were published in Dhaka between 1863 and 1900. Besides the bookshops, some local agents were also involved in selling them. The authors used to describe the whereabouts of the sales centres in rhymes inside the book. One such example:

এই কেতাব যার দরকার হইবে

নিজ দোকানে মেরা আসিলে পাইবে

মিয়া রবিউল বটে ভগিনী জামাই।।

দোকানে থাকেন সেই পাবে ঠাঁই।

চওকের পশ্চিম ধারে কেতাব পট্টিতে।

ঠিকানা বলিয়া দিনু সবার খেদমতে।।

With the expansion of the publishing business, bookshops also sprang up in various parts of Old Dhaka, particularly in Chawkbazar, Islampur, Mughaltuli and Patuatuli. It is estimated that the number of bookshops in Dhaka till 1900 were no less than 40.

In the first half of the 20th century, book trade in Dhaka grew steadily. During 1905-12, when Dhaka became the capital of the new province of East Bengal and Assam, it saw a rise in its publishing business. However, that prosperity didn't last long.

Increasing political consciousness among the young people in Dhaka following the Swadeshi Movement was also reflected in the book trade. Veteran politician and writer Sardar Fazlul Karim wrote in his memoir about one such bookshop, Albert Library, which was home to Dhaka's communist activists and progressive thinkers. The Library was located on the west side of the junction of Bangshal and Nawabpur road. Prominent Communist activist Gopal Basak was its proprietor. He was arrested on the charge of conspiracy in the famous Meerut Case (1929). The main attraction of the bookshop was its collection of foreign political literature.

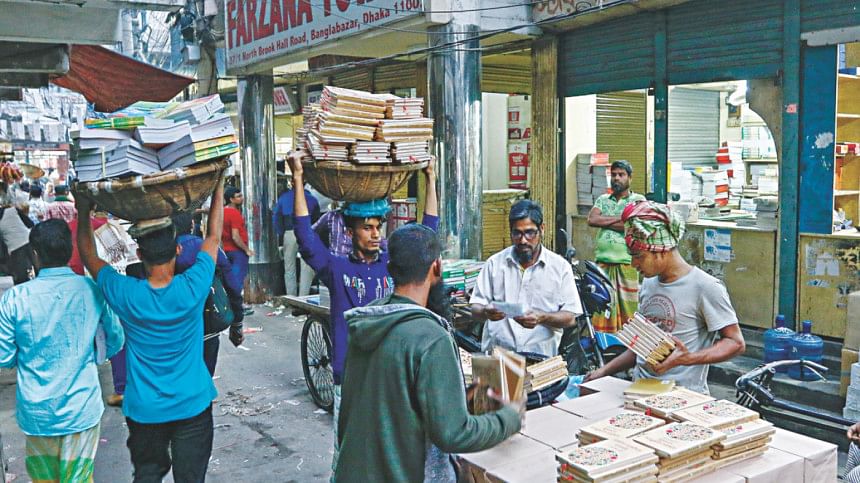

Calcutta dominated the book trade in Bengal until 1947. The Partition, therefore, proved to be a boon for the book business in Dhaka. However, only the Muslim traders were able to reap the benefit. Whereas there were only 27 publishers in Dhaka in 1947, the number rose to 35 by the 1950s and 88 by 1965. Most of the new book publishing houses were owned by Muslims. Prominent among them were Naoroz Kitabistan, Tamuddin Press, Pakistan Cooperative Book Society, Mullick Brothers. The main concentration of the bookshops in Dhaka gradually shifted to Bangla Bazar areas during this period.

Mizanur Rahman's memoir, Dhaka Puran, provides a glimpse into the emerging book market : "The three-storied building of the School Book Society is still fresh in my memory. Not far away, at the head of Simpson Road, was the Islamia Library who migrated from Calcutta; Osmania Book Depot was on the right lane of Babubazar's junction and Makhdumiya and Ahsan Ullah Library was located near the Babubazar Pool. There was another book market Chawkbazar – the smell of the British and Mughal periods was still found in that area."

Among the newly arrived book entrepreneurs, two deserve special mention. At the corner of Victoria Park, a new bookshop named Presidency Library was opened by the famous football player Shahjahan. He was the captain of Kolkata's Mohammedan Sporting Club. After the Partition, he migrated to Dhaka.

Another one is Mullick Brothers. During the Calcutta Riot, the proprietor of the bookshop, Rajab Ali Mullick, lost their shop. He and his brothers migrated to Dhaka and started from scratch. Initially, they had a small bookshop at the corner of Sadarghat. Within a few years they became a major publisher and importer of books in Dhaka.

A new group of workers also arrived after the Partition. Interestingly, most of them belonged to Harirampur of the then Manikganj subdivision. They used to work in Calcutta in the printing trade in various capacities. They left Calcutta after the partition in 1947 and settled down in Dhaka.

With the coming of Muslim writers, poets, editors and publishers from Calcutta, a new form of modernity started to emerge. Take the example of Syed Waliullah. In 1946, he started a publishing house named Comrade Publishers in Calcutta. Following the Partition he moved to Dhaka, and published his famous novel, Lal Shalu, in 1948 from his own publishing house. His masterful mingling of the elements of modernism and existentialism in Lal Shalu left a permanent impression on post-Partition Bangla literature.

However, the intellectual effort to build the literary culture of the new state along Islamic ideals also reflected in many literary works published immediately after the Partition.

Shamsul Huq, in his bibliography of Bangla literature published between 1947 and 1969, opined that in the initial years after the Partition, the prosperity in book trade was limited to text books, and after 1957-58, publishing of creative works flourished significantly.

This article will remain incomplete without the story of Wheeler's bookstall. It was the leading importer of foreign books and journals in Dhaka. The bookshop was located at the entrance of the old Dhaka Railway Station, popularly known as Fulbaria Railway Station. It was a bookshop chain which had branches at every major railway station all over India. The first bookstore of Wheeler was opened at Allahabad (India) railway station in 1877 and they still run their operation from the area. After the Partition, the link with Dhaka's Wheeler gradually became weaker and finally, the bookshop was closed in 1968 when Dhaka Railway Station was shifted to its present location in Kamalapur.

Shamsuddoza Sajen is a journalist and researcher. He can be contacted at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments