The dark night memories of 25 March 1971

Upon hearing the news, an unprecedented reaction engulfed the spectators. The crowd turned into a raging mass, a huge hue and cry with nationalistic slogans soon filled the galleries and echoed around the cricked field. Some of the spectators collected the newspaper and set those heaps of paper on fire.

The suspension of the first national assembly session at Dhaka by President Yahiya led to a dreadful consequence, beyond the imagination of the people of Pakistan, and one which would change the course of history forever.

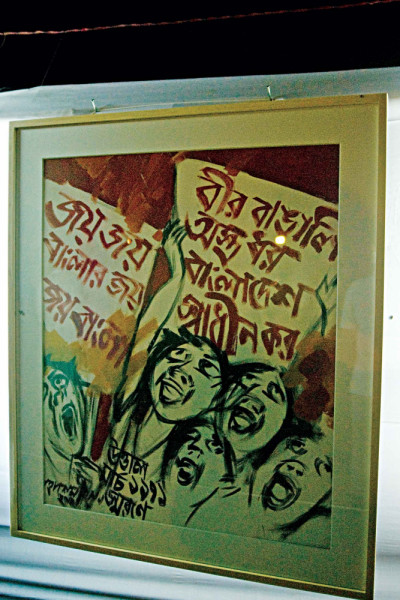

On 7 March, 1971, Bangabandhu delivered his historic speech at Ramna Racecourse in front of a colossal crowd of thousands of eager people, and this became the turning point for the Bangladesh Liberation movement.

My friends and I, along with thousands of others, marched and joined this historic assembly chanting political slogans. His speech inspired people and gave them light and hope amid the darkness of political conspiracies. Bangabandhu told the people that this struggle was for freedom and liberation.

A non-cooperation movement against the Pakistan government started as directed by Bangabandhu. All government offices and bodies, as well as business, other than emergency services, were shut down. Meanwhile, President Yahiya negotiated with Bangabandhu to resolve the political crisis. Yahiya was seemingly killing time in collusion with his political partner, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, as a part of a far-fetched conspiracy to keep political power with them.

As the issue of transferring power became more and more imminent, a political crisis threatening to tear apart everything was brewing. Ultimately, the political crisis remained unresolved, and as a consequence of the Yahiya and Bhutto conspiracy, Operation Searchlight and the genocide of Bangladesh became a grim reality.

25 March, 1971

The atmosphere was tense that evening of 25 March, 1971 and numerous rumours circulated — with ominous warnings for what was to come that night. We were gathering at Mailbagh crossing, and mingling with the bewildered crowd. Some groups were chanting slogans and waving the Bangladesh flag.

People were getting contradictory information from one another, precipitating confusion in the air. Some of my friends were at the meeting with the revolutionary council members and confirmed the rumours to be true — the army would crack down on Dhaka at night. An unknown fear gripped the people's minds.

Throughout the entire month of March 1971, we had received secret guerrilla training. We were recruited from among the most trusted members of the Student League, the student wing of Awami League. We were trained with dummy rifles, a kind of wooden piece carved into the likeliness off a 303 single fire rifle usually used by the police. During the evenings of the turbulent days of March, theoretical training classes were taken by a retired Bengali army officer.

Based on the training that we received, on the evening of 25 March, we organised the people and erected barricades on the major roads to stop the advancing platoons of the army in their armoured vehicles. A strong sense of Bengali nationalism permeated the volatile political atmosphere. People from all walks of life united to halt the advancing army.

There were some steel pipes stacked beside the road. During that period, there used to be strips of empty land on both sides of the roads with rain water drainage facilities; many company vehicles and heavy equipment were parked there. The frenzied mob moved those structures to the road, thus blocking the passage of normal traffic. On the other side, the Malibagh-Mouchak road was also blocked with bricks and other structures. In the meantime, some members of the police force appeared from the adjacent Rajarbagh Police Lines and lent us a helping hand to erect a formidable barrier of steel structures.

At around 10 o'clock at night, the sound of gunshots penetrated the thin air, coming from the airport and adjacent areas. The police force took charge of the situation and dispersed the chaotic public, told them to evacuate the place, return and stay home. They busted the street lights to darken the streets so that the enemy force couldn't locate them. The police soon disappeared into the darkness of the chilly night and took offensive positions on the roof of the CID and DIG building.

Soon, we realised that the final hour has arrived and the army was on the loose. Unfortunately, we were all unarmed. Although not terrified, but without weapons, nobody could stand a chance against trained armed forces.

I returned home, informed family members of the situation and told my parents and other members of the family to take shelter, and lie down on the floor at the back of the house. As time went by, gunshots were coming nearer and then suddenly everything fell quiet, into an eerie silence; even the street dogs stopped their usual clash of clans — the nocturnal creatures went into hiding.

I was lying on the floor with my family members. Only my elder brother, Azizul Huq Chowdhury Kaoser, was not with us. He was organising secretary of Dhaka City Student League and an active member of the secret group. I assumed that he was with his political aides to deter the army's aggression.

Soon, the sounds of gunfire from automatic weapons and military vehicles became distinctive. An unknown fear went through my mind and I was gripped by uncertainty. Sounds of firing by machine guns were soon heard. They had broken the barrier!

The Pakistan army attacked Rajarbagh Police Lines from all directions. The police fired back and we recognised the sounds of the 303 rifles.

In retaliation, the Pakistani soldiers soon superimposed the rifle shots with their powerful automatic modern weapons. Heavy fighting soon ensued between the armed sides. The sounds of bullets were reverberating around the buildings. Every now and then, tracer bullets illuminating the night would flood the darkness of the night with so much light, they made the police easy targets, as if they were standing in plain daylight. Bullets were raining on them from all directions. We had no prior experience of how the ground shakes in a war zone being showered with artillery fire. For the first time in my life, I smelled gun powder. The sheer number of bullets made the atmosphere dense with smoke from the gun powder.

Suddenly, the Pakistan army set fire to the corrugated barracks at the eastern side. Ultimately, all ammunitions were exhausted and the sound of single shots became more and more scattered, indistinct. The remaining police force started to escape to save their lives. Some of them came running through the narrow alleyway between our houses; couple of them knocked on our house asking for escape routes. I directed them towards the Mouchak Road behind our house. I don't know the ultimate fate of those escaping policemen. Apparently, many of the escaping police were wounded, but we were helpless as the army was still carrying out their killing spree. We were just listening to the horrific sounds of gunfire and waiting for all this to be over!

26 March, 1971

Slowly, the sound of gunshots died down. A chilling fear crawled up my spine. We were petrified that soldiers might carry out a house to house search and go on a killing spree. At last, the darkness of the night disappeared as dawn broke, every now and then, the silence shaken by the sound of passing armoured vehicles.

After a while, I gathered some psychological strength and stood up. I slowly walked down to the front of my house and opened the door a little bit, peeping through gap. The roads running along the two sides were empty, not a single creature could be seen.

Soon, I heard the sound of an armoured vehicle. A heavy truck carrying some soldiers was on its way to the Rajarbagh Police Lines. All the soldiers were sitting alert with their weapons in hands. Another one was standing behind the driver's cabin with a LMG on the roof.

A dense cloud of black smoke was rising from the still burning barracks and covered the eastern sky, the sun yet to be clearly visible. Hot air was blowing from the devastated burnt ruins, intermittently whirling around the empty spaces, carrying a distinct pungent smell towards our house. Now the whole area was permeating with the burnt smell. The dawn stretched a bit longer. Since it was a deliberate attempt by the Pakistan army, the thought of firefighters coming to help was beyond our imagination, though a firefighting station was just across the police barracks.

I started moving with my family members — my parents, three brothers and a sister. My elder brother, Kaoser, was still missing. It was presumed that he had been staying with his action group somewhere near Dhaka University.

I came out to assess the situation and walked down the narrow lane leading to Malibagh-Shantinagar main road. Many curious faces popped up on the neighbouring windows. It seemed to me that they were eagerly waiting to see a living creature walk on the road. Somebody told me in a low voice to go back.

Suddenly, my friend and neighbour Mahboob appeared before me. He gave me a big smile. I assured him that my family members are all ok. We both started walking towards the main road, which was partly visible. But we soon hurried back as the sound of a heavy armoured vehicle drew nearer.

We hid ourselves in a corner; the army truck went past. Ultimately, we dropped the idea of going to the street. From that moment on, we just kept an eye on the changing situation and waited eagerly to take a view of the main road.

It was possible for me to see the roads and adjacent areas, but fear of death prevented me from acting on the strong desire to run to the main road.

The whole locality was abnormally quiet, as if every living creature went into hibernation. The stray dogs also disappeared; their barking had not been heard since last evening. The chirping of the morning birds and harsh cry of the crows was also absent.

We finished our breakfast with whatever food was at our disposal. Most of the time, I tried to look through the door. I instructed my family members to not open the door or windows on the waterfront side and to move cautiously inside the house. We were talking in a very low voice as if we were whispering to one another. We decided to listen to our battery-operated transistor radio. We timidly gathered around the radio; the regular programme was interrupted with some government instructions, on repeat. Some religious programmes were being aired as well. President Yahiya Khan said in a nationwide radio broadcast at night that Awami League would be completely banned.

The Aftermath

At that moment, people all around the country had no idea that unprecedented atrocities were carried out around Dhaka city and elsewhere in the country. Even we were completely unaware about the mass killing and devastation.

The news of battle against the army spread quickly; also, the news of mass killings in Old Dhaka, predominantly in Hindu areas, and the attack on Dhaka University Iqbal Hall and Jagannath Hall spread in the city like wildfire.

Members of the Nucleus and other students who escaped the onslaught of Pakistan Army revealed the horrific situation at Dhaka University campus on the night of March 25.

On the night of the 26th, a member of the Sareng Bari offered us shelter. The homemaker, Mrs Sareng, was very kind and helpful. We were amazed at her hospitality as she offered beds and quilts to us. Nights and early mornings were still chilly during spring time in late March.

Next morning, after returning to our homes, we became busy making breakfast for the family. Next day, on 27 March, 1971, a radio announcement informed us that curfew would be lifted for two hours to facilitate the members of the public to purchase food and other necessary items.

The moment had arrived. Curfew was relaxed after ten o'clock and we were out. My father went for shopping; my brothers and sister, along with my mother, came out from the hideout and set foot in open space.

I walked down the narrow lane leading to the main street. At the end, many other onlookers assembled and looked around to see the devastation. I met there with my friends Azad, Mahboob, Karim and a few others, juniors and seniors.

We could clearly see the streets and adjacent buildings. The black smoke still came out from the burnt barracks on the eastern side, an acrid smell blowing intermittently from the wreckage. We were astonished to see the DIG and CID buildings were riddled with bullet holes, like a honey comb. Several gaping holes, seemingly from artillery fire, were visible. All of a sudden, a man appeared before us from nowhere; walking like a zombie, tumbling like a drunk. We were astonished to learn that he was hiding inside the rain water drainage system, running along the roadsides to save his life during the battle. He had been late in going home that night, and got caught in the warfare. Luckily, the dry drains were like a trench that saved his body and covered him from the sight of the army and crisscrossing bullets, although they were firing the cannons only a few feet from him.

A feeling of uncertainty gripped us. We did not know what was to become of us. We all felt insecure, but were happy to be alive.

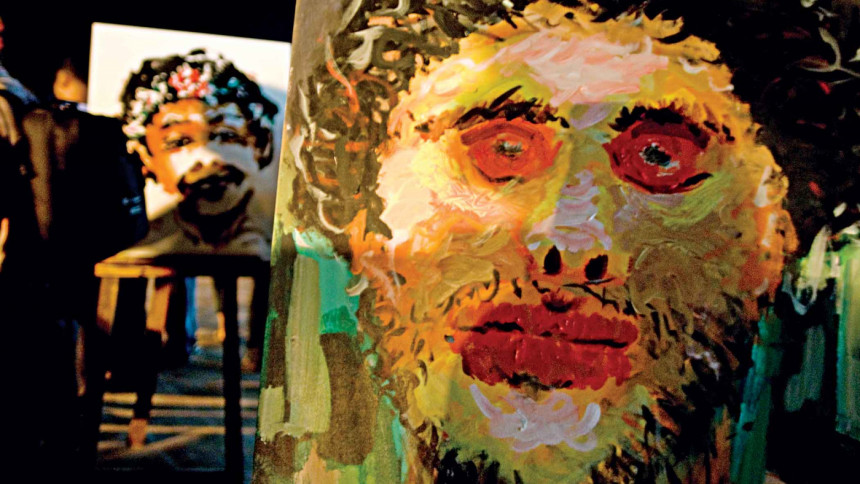

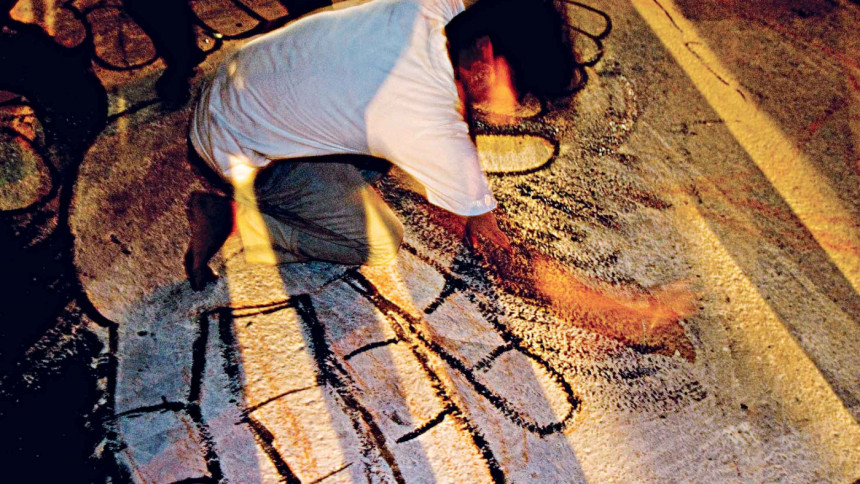

Photo: LS Archive/Sazzad Ibne Sayed

Sanaul Huq Chowdhury is a retired marine engineer. In 1971, he was a student of Dhaka College. Politically alert from that age, Chowdhury played an active role in student politics. This week, 50 years since that fateful evening, he shares his experience of the dark night that was 25 March, 1971.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments