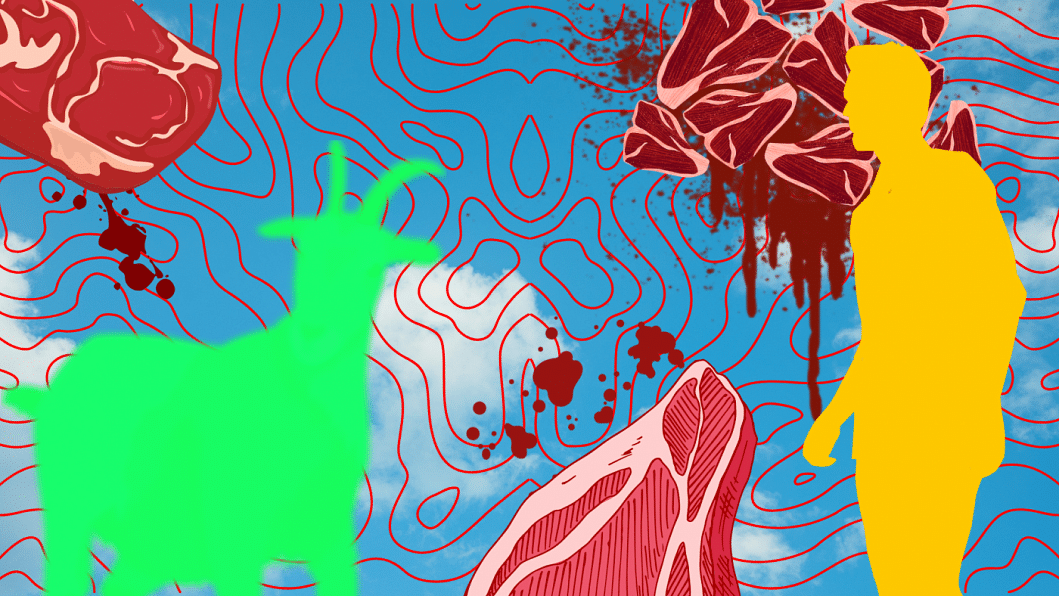

You are what you eat in Mashiul Alam's "The Meat Market" (trans. Shabnam Nadiya)

Eid-ul-Azha is an interesting time of year here in Bangladesh. We make peace with encountering an expected amount of gore. Blood and carcass. Mounds of flesh. Some lumped into transparent packets and others strewn in speckles across the floor. The smell of this sacrifice pervades the air in our streets and foreshadows the meals we will soon consume. At the same time, we wrap our minds with a cocoon of obliviousness. Residents of Sirajganj are starving from river erosion as we speak, their homes having been devoured by the Jamuna river; at least seven dengue patients have been hospitalized around the country in the last 24 hours; and a The Daily Star editorial published on July 8 confirms 476 cases of sexual abuse of women in Bangladesh in 2022 so far. Yet our streets are silent, and for the next few days of holiday, we believe all is well and calm.

But is it?

Mashiul Alam's "The Meat Market", translated from Bangla by Shabnam Nadiya, is a short story that stays on my mind every Eid since I first experienced it in Niaz Zaman's The Demoness: The Best Bangladeshi Stories, 1971-2021 (Aleph Book Company, 2021). It is a story of discomfort. Of calm, ruthless violence. A drag-your-hands-down-to-uncover-your-eyes gaze at the oblivion we practice not only during Eid holidays, but on any regular day in Bangladesh.

Alam's protagonist-narrator Aminul Islam is woken up by his wife at dawn to go pick up some khashi for Eid cooking. He addresses the reader directly early on, a foot each planted on the world of the story and that beyond it. This is perhaps the only hint we get that something sinister lurks beneath an ordinary day unfolding in his life. As he walks out into the city, sights common to Eid-ul-Azha spring up around him—"the black tar of the road [...] soaked dark red with blood." Aminul has arrived at the butcher's, where he is given sheep in the name of khashi. When he protests, a shocking blowback ensues. In characteristic Bangladeshi fashion, other customers and pedestrians "looked on with childlike curiosity, some with their hands resting on their hips, some with their weight resting on one leg, as if watching monkeys perform on the streets."

This thing we're so skilled at—the ability to look past injustice—is a central concern of this author's. In his 2019 Himal Short Story Competition prize-winning "Milk", also translated to English by Shabnam Nadiya, Mashiul Alam writes of a malnourished child who is breastfed by a dog. When the villagers look on while the dog is beaten to death by the child's father, birds, bugs, fireflies and the wind coalesce into an orchestra of mourning for the crime. Nature retaliates and cleanses the village with a giant flood of milk. I watched a student shed tears at the scene when I taught it in class last month.

In "The Meat Market", Alam delivers a similar blow to the heart that is quieter in volume, more chilling than happy and fantastical. He forces our eyes open through a crime recounted in blood curdling detail. Like the scene's onlookers, we ignore and forget countless wrongs in this country every day: murders, kidnappings, rape, corruption, arson, Aminul counts. The narration risks sounding preachy and repetitive in these moments, even though the plot itself very elegantly gets the point across.

However, "it takes some effort to get at the brains of goats or cows; a human's skull is no softer", he tells us soon after, and in such sentences which make up the larger part of the story, the narrator achieves a beautiful balance of irony, clarity, even humour.

Zoom out, and you notice that the event is recounted in scenes, in sections marked by numbers much like "Milk" is. It is a ticking time bomb. A tragi-comedy in 5 acts that manages to become about other things that are a vital part of life in Bangladesh: pollution in trade, pollution in the things we eat, karma always in motion. "You yourselves are making them happen", Aminul reminds the reader. To illustrate the point, his family literally eats the results of their ignorance. That perhaps we do too is the underlying message of the story.

We can choose not to read something like this at a time when we would like to forget all the many ways we accommodate injustice around us. "Some light reading" is what we're after, or the next Netflix treat perhaps. Or, maybe, literature crafted with a conscience, with power, can help make better use of the downtime.

Sarah Anjum Bari is Editor of Daily Star Books and Adjunct Lecturer at the Department of English and Humanities, University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh. Read her at [email protected] or @wordsinteal on Instagram.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments