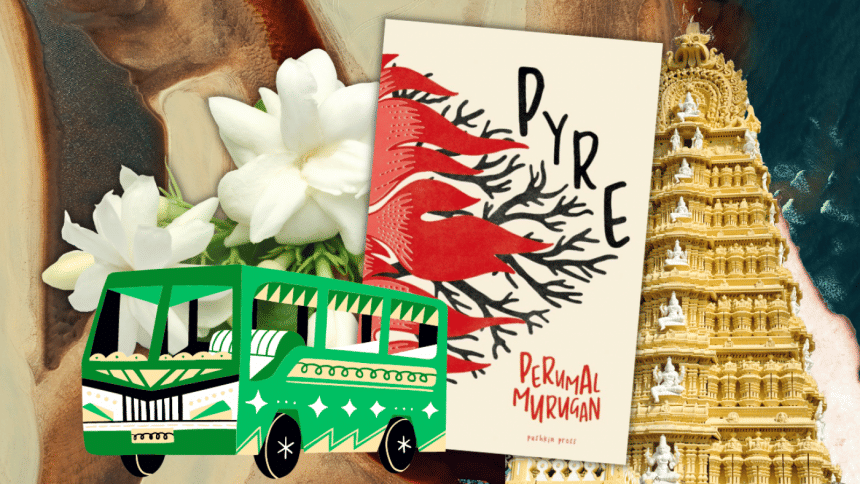

Love and caste collide in Perumal Murugan’s 'Pyre'

Coming from a family that boasts numerous elopements spanning generations, perhaps I am uniquely suited to talk about Perumal Murugan's Pyre. I have seen, first-hand, the shake-ups of loyalty, the attempts to disinherit one's own and the clear revulsion that stories of runaway love bring. Murugan's novel is, in this regard, a familiar read that takes on these issues with memorable simplicity. Translated from the Tamil by Aniruddhan Vasudevan, Pyre is a love story that is a thrill in the vein of Murugan's contemporary, Vivek Shangbhag's Kannada novel, Ghachar Ghochar (2015), though it is darker, far more serious and nerve-racking in how it accelerates toward its mordant end.

It is the story of young lovers, Kumaresan and Saroja, who get secretly married and run away to Kumaresan's village to start a new life. Murugan has written before about the intricate tragedies of domestic life and how they bring about the worst of our community. In his novel One Part Woman (2010), through which I first discovered the author, a couple is unable to have children, a predicament that leads them to consider going to the festival of an androgynous god where social taboos regarding sex are relaxed. The literary merits of the book failed to surpass right-wing propaganda, as is usually the case, and the book came under fire for being "controversial". Murugan, in dramatic fashion, even quit writing. In a Facebook post, he said, "Perumal Murugan the writer is dead. As he is no God, he is not going to resurrect himself. He also has no faith in rebirth. An ordinary teacher, he will live as P. Murugan. Leave him alone."

Fortunately, after a High Court ruling that dismissed any need for him to apologise or withdraw his book, he did resurrect.

Pyre's beauty lies in the gradually ascending intensity of its story. Kumaresan's mother, a widow since the age of 20, claims victimhood for this act of "betrayal" her son has committed. Her actions mimic pitch-perfectly how some mothers react to situations of this order in the sub-continent: "I had thought my son would earn some money and walk with his head held high among the people here. But he has thrown fire on me. If he had been killed in a road accident somewhere, I would've written it off as my destiny," she cries, "What did you do to bewitch my son?"

Kumaresan comforts his wife that the hostilities are temporary. "For a few days," he advises her, "take off your ears and keep them aside. Put them back on only while talking to me….everything will be all right."

Yet, that is often easier said than done. Kumerasan's naivety soon catches up on him and he starts to drink, frustrating Saroja even more, who feels as if "all her certainties [are] collapsing." Her dependence on Kumerasan worries her, though she continues to believe in his advice.

Meanwhile, casteism colours the villagers' ability to accept the new couple. It affects every decision in their village. Kumaresan himself had been barred as a child from working with the day-labourers, for he would be mixing with men from other castes. Murugan deftly renders the inhumanness of caste discrimination through Saroja's ordeal. We are never told which castes they belong to, though it is certain they are from the South. The ambiguity helps Murugan's realist take on the issue of caste; eschewing any ray of hope, he settles for despair. As Saroja faces the village's snark daily, we see her wait for the better times culminating in a pastoral savagery that is hauntingly biblical.

The singeing heat, the "vast expanses of arid land," the large rock that dominates the landscape of the book all simulate the tone of Saroja's helplessness in her new environment. Murugan is essentially a writer of great sentimental talent, possessing a realism found in the likes of Bibhutibhushan. That is Pyre's gift to literature: Murugan's adeptness in marrying the psychological anguish of his characters with the social realism of familial bonds. Aniruddhan Vasudevan's English version has excelled in sifting up the story's humanist, regional essence (from soda shops to kuzhambu dishes) from the usual contextual entanglements of translation.

Melancholy and brutal, one wonders if Saroja's jam started the moment she decided on the need for obedience as a way of navigating through her new community. Perhaps she should have held her ground from the start. Perhaps, to crack the boulder of caste, class, and colour, one mustn't tap light in hopes of chipping it away incrementally but to take a hammer and swing at it with violence in mind.

Shahriar Shaams has written & translated for SUSPECT, Third Lane, Adda, Six Seasons Review, Arts & Letters, and Jamini. Find him on twitter @shahriarshaams.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments