In conversation with South Asia’s preeminent literary agent, Kanishka Gupta

As an editor—emerging or experienced—one of the truths you swallow on the job everyday is that editing is a backstage job, integral and constantly mutating, unnoticed, with the hour's need. You tease out an idea almost at the tip of the author's tongue (fingers?), probe them to reckon with the perspectives they're bringing to a work, look into the research, the formatting, the promoting—all the less romantic parts of getting a piece of writing out into the world. The labour of these tasks hangs hidden, in the spaces between the sentences we read in print, on our phones and computer screens.

If the job of the editor contains dozens of these tasks, the literary agent performs perhaps tenfold of that. It is the agent who, in mature publishing ecosystems around the world, guides the author through the stages of finding the right editor, preparing the manuscript for the right publisher, and then marketing the book to the right readers, all while protecting the author's legal, financial and creative interests.

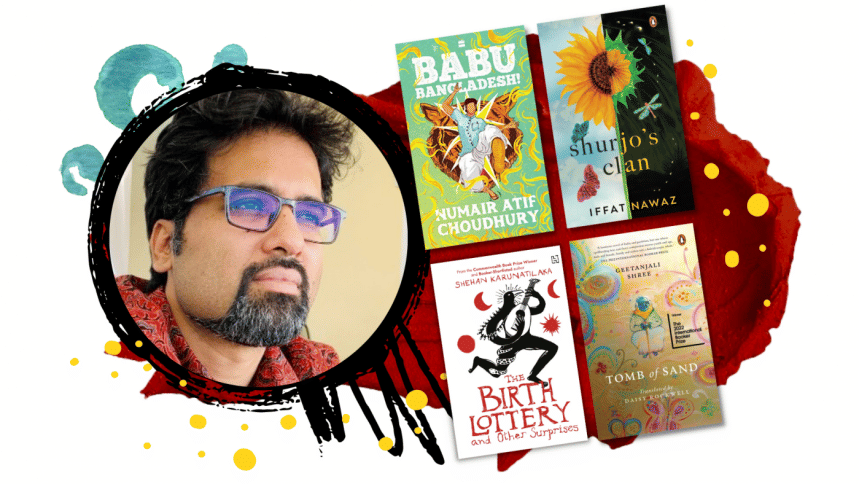

Kanishka Gupta is a literary agent who founded Writers Side, Asia's largest literary agency based in India, and some of the authors he represents have been at the forefront of literary conversations in recent years, his and their work having taken South Asian literature to a global stage. Shehan Karunatilaka, Sri Lankan author of the Booker Prize winning The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida, is represented by Kanishka in South Asia for The Birth Lottery and Other Stories as well as his forthcoming novel. Daisy Rockwell, translator of the International Booker Prize winning Tomb of Sand, is represented by Kanishka for all her work globally, as is Geetanjali Shree, the author of Tomb of Sand, for the English translation of some of her backlist titles within the subcontinent. The list also includes Avni Doshi, the Booker Prize shortlisted author of Girl in White Cotton, Numair Atif Chowdhury, Bangladeshi author of the majestic, posthumously published Babu Bangladesh, and Iffat Nawaz, the Pondicherry-based Bangladeshi author of Shurjo's Clan, among others.

In person, Kanishka is as humble as his authors are prominent. It is his passion for storytelling that comes through in conversation, alongside an instinctive, entirely self-taught (and, in his words, utterly bizarre) understanding of the publishing system. Something interesting happens when I begin our virtual interview—unlike the authors, journalists, publishers and artists I normally have to ease into talking about their work, Kanishka rattles off answers to most of my questions about the South Asian publishing scene before I even have a chance to ask them.

What does the agent do for the author?

It marries a lot of professions—you're a reader, lawyer, counsellor, editor, friend.

An agent should have a very good understanding of the market and the requirements of all the editors and publishing houses. I would not want to work with an agent who has access to just one publisher in different houses in India—there are 8-10 commissioning editors at HarperCollins and Penguin, and each one of them is looking for a certain genre. Some of them are looking for a certain kind of book within a genre. So the agent should have a very good knowledge of publishing trends, of what kinds of books are selling.

At the same time, an agent should not be mercenary, they should not say no to good manuscripts just because they feel like it will face a lot of resistance from publishers. You have to be passionate about the book and sometimes you have to be okay with knowing that a book will not do well. But sometimes an auction that starts at 1 lakh can end with 10 lakh.

Authors also expect us to be very proactive about pitching their books to OTT platforms. And then you obviously have to make sure the contract protects the interests of the author in terms of the copyright, the royalty percentage, that there are no clauses which sound shady, etc.

What do you look for in a manuscript, and how does that differ between genres?

Fiction is a very instinctive thing. Short stories are as hard to sell as poetry. But with fiction we make sure that the most fundamental things are correct—the quality of writing, storytelling; even if it is experimental, it should not be so for the sake of experimentation, and it has to be original. I'm happy to take works of fiction or creative nonfiction that work with hackneyed storylines as long as it's done in a new way. For instance, there are so many mother-daughter feminist narratives floating around, but some of them are done in such a fresh way.

If it's political nonfiction or biography, the research is more important than the writing. If it is a book on a historical figure or event, I like to ask the author what new thing he/she is bringing to the table.

So you've said yes to a manuscript. What happens next?

Sometimes we say a provisional yes—they work on it and get back to us. If we feel that it's next to impossible to pitch the book in its current state and we don't have the editorial and financial wherewithal to edit in house, we recommend freelance editors. If we're convinced after the authors come back, we do a standard author-agent agreement.

There are authors who want me to represent them in India only; some of them want me to represent them globally. There are authors who have 2-3 representatives in South Asia or globally.

So after the contract we do the pitch note—it's somewhere between a synopsis and the book jacket blurb. We work on the author bio, making sure that it focuses on the author's writing credentials and not just their achievements. Sometimes if we feel that a book is a hard sell, we get authors to prepare marketing plans. Then you kind of nudge other publishers and tell them that we've got other offers and give them a deadline for a response.

The publishing side usually takes 10-14 months.

I always tell the authors to make subjective, qualitative decisions. So many of my authors say no to higher offers from publishing houses if they don't feel comfortable with the publisher or editor. Some of them want to work with editors who are more hungry because they are new themselves.

What are some of the things an emerging or aspiring author should know about the publishing process?

Read a lot of books. If you're writing fiction, ask yourself, why should someone invest money in it, edit it, publish it? Will this story have a wider resonance? Or is it just a form of catharsis for you?

The story needs to have a universality, finesse in the plotting. Your research sources have to be more than Google search. You should have travelled to the places where some of your characters or stories are set.

Be open to feedback, don't be in a hurry to publish.

And—maybe this is a controversial statement—don't hero worship 2-3 writers and emulate their styles, and don't get so swayed by market forces that you are not experimenting enough. Just write.

Tell me about your work with Numair Atif Chowdhury and Babu Bangladesh.

Numair was introduced to me by Nadeem Zaman. He was not dismissive of me, nor was he reluctant. But for the longest time he was very wary of sharing the draft of Babu Bangladesh with anyone from publishing.

When I visited Dhaka after Numair's death to chair a session on Babu Bangladesh, I found his thesis for the novel at Lubna's house. You'll be surprised that there were not too many changes in that draft from 2007 or 08—we're talking about 8-10 years before the manuscript.

We had several conversations and it took me a long time to get the manuscript out of him, which would mean that he would have to let me read it. So the draft came to me. In a day—and it was a working day—I spent half of it reading the text, while I was supposed to be responding to mail and calls. A lot of people say that parts of the book feel like nonfiction. That's the compulsive, hypnotic quality of the book.

Numair eventually said yes but he was not willing to do any paperwork. He was also teaching in a university and I remember he was deeply disturbed about the political unrest, the attacks on students that happened in 2018. I think somewhere down the line he started worrying about his safety because of the nature of the book—because it is explosive.

He passed away, and then I was very nervous that the book would go to someone else. I was also anxious to reach out to the family at a time like that. And this is where relationships come in—I repitched to the family.

Numair comes from a family of intellectuals and avid readers, they are very particular about quality, and they were very closely involved in the process [of it getting published]. The book was pitched and immediately I got an offer. None of them told us to make any changes. But I'm pretty sure that Numair would've wanted to work on it a little more.

Who else are you working with from Bangladesh?

I've just signed a collection of 14-15 stories by Kazi Nazrul Islam, who is also very big in India. His grandson is translating a selection of his stories culled from the short story collection. Not much is known about his short fiction. A lot of it is set during World War time and it's also about the experiences in the regiment. These are formative years so it's a glimpse into the factors that turned him into this poet.

Noor Jahan Bose's Daughter of the Agunmukha is out in July or August, published by Hurst Publishers and translated by Rebecca Whittington. Hurst is very excited about this book—it's basically her life written in a very novelistic way.

I represent Rifat Munim now, who is translating a novel by Shaheen Akhtar. There is also Phantom of the August, a novel by Mashrur Arefin translated by Arunava Sinha which will be published by Vintage India.

Shah Tazrian Ashrafi [a writer for Daily Star Books] is just 20 years old and he is writing short stories! His book was picked up by Hachette India and it'll probably get a global deal.

Among the writers I've worked with, I seriously feel that Babu Bangladesh was on another level. I liked Shurjo's Clan—it's the kind of book that can appeal to a large readership and Iffat has worked quite hard on it.

I do admire the works of Saad Hussain—he's wacky and has a lot of flair even though it's difficult to make it as a speculative writer. I have great admiration for Leesa Gazi, Shabnam Nadiya.

What's your take on plagiarism in South Asia? It's become especially common in Bangladesh.

I think it's very bad in Bangladesh. I know Indian publishers refuse to let go of Bangladeshi rights because they feel that their books will be pirated. Publishing houses in Bangladesh have approached Indian publishers asking if they can print a novel in Bangla so that there is better distribution in Bangladesh. Every single time, there is only one reason cited for why the Indian publisher did not agree: piracy.

Piracy is quite rampant in some of the Indian language publishing scenes too. Forget pirated editions, PDFs are being distributed on WhatsApp.

The change has to happen at a government level. This is an industry which is not even recognised as an industry in India. There is increased GST on ink, on royalty—authors don't even want to publish in hardback anymore. I tell some authors to go for a paperback because for a new writer, the book will not sell at Rs 799. So the authors also need to be sensitised to this.

How has all this experience of working with books changed your sensibilities as a writer and reader?

It's killed the writer in me! All the time you're talking to writers who are, sometimes justifiably, convinced that their book is the greatest book ever. This is the kind of conviction that you hear day in and day out. So I don't have any writerly ego left. It has not been conducive to me as a writer.

But I do feel that in the long run, when I take a break—and I will—the richness of the books I've read, the people I've met and the encounters I've had by virtue of being a publishing professional will make me a much finer writer.

I don't find much time for pleasure reading but I've become very discerning. I do want to take a break and read the kind of books that I like to read—literary and experimental fiction. I don't like reading science fiction.

I think we don't read with that sense of lightness and wonder anymore, I don't find the time for this.

But one of the books that really stayed with me is called The Piano Teacher by Elfriede Jelinek. From South Asia one of my favourites is Temporary People by Deepak Unnikrishnan—experimental, crazy stories about the immigrant experience.

Sarah Anjum Bari is Editor of Daily Star Books. Reach her at [email protected] and @wordsinteal on Twitter and Instagram.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments