Why the new budget can't solve our problems

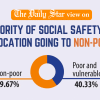

As it does every year, the budget for this fiscal year reflects some good initiatives. Duties have been raised for the import of luxury goods, and the individual tax ceiling has also been raised. The social safety net programmes have been expanded by some margins, and allowances have also been raised to some extent. Some new taxes, like the carbon tax, have been imposed. Taxes have been raised for the registration of flats and lands, purchase of a second car, and travel.

The key question, however, remains: to what extent have our current economic challenges been addressed by the new budget? It hasn't done proper justice to answer this question.

There are two major challenges confronting our economy: inflation and the management of macroeconomy. Inflation currently stands at around 10 percent. Such a high inflation rate has been prevailing for over a year. This has had a significant impact on a large section of the population, especially poor and low-income people. But it is still unclear what measures and strategies will be used to combat inflation in the coming days. Also, there are no clear directives as to what should be done to deal with the economic crisis, mismanagement of the financial sector, and revenue collection.

Considering the current situation, some of the ambitious targets of the 2023-24 budget seem to be out of context. The budget aims to reduce inflation from its present level to six percent. This would have been achievable had the government's initiatives and plans so far been successful. Unfortunately, the policymakers neglected to adopt the policies and plans that they ought to have. It is therefore important to demonstrate how there will be a departure from the past unsuccessful actions and how the policymakers will be able to take the right measures in the coming days.

Little action was there where it was needed most to combat inflation. First, in the case of monetary policy, the interest rate was forcibly capped for a very long time, which made no difference in reducing inflation. Second, by adjusting taxes and other fees in the revenue sector, prices of necessities could be lowered. For example, with the rise in fuel prices in the global market, they were also raised locally, though there was another option to keep the fuel prices at a tolerable level by adjusting taxes. The dramatic rise in fuel prices affected almost all sectors of the economy and escalated inflation. Third, in the case of domestic market management, as there were serious allegations of anti-competitive practices, strict measures were not taken against traders involved in price manipulation by creating artificial crises.

Now, there is little to blame the Russia-Ukraine war for inflation. Though prices of essential items have been falling in the international market for over a month, there is no reflection of that in the domestic market. Except for Sri Lanka and Pakistan, Bangladesh performed poorly in containing inflation compared to others in the region, such as India, Vietnam, and Indonesia who, by effectively utilising monetary policy, revenue policy, and domestic market management, have been able to keep their inflation rates at a much more tolerable level.

Another anomaly in the budget is that it anticipates an increase in the private investment share of GDP from 22 percent to 27 percent within a year. However, the private investment share of GDP remained stagnant at around 22 percent for over a decade. In the past, private investment has never dramatically increased in a single year. Therefore, this target of private investment comes rather from a mechanical calculation and is far from reality. As the government sets a target of a 7.5 percent GDP growth rate, considering the Incremental Capital Output Ratio (ICOR) of 4.4, this very ambitious target of private investment is set. There is, however, no sign yet in the economy that private investment will increase dramatically soon.

There is yet another contradiction. The budget deficit as a percentage of GDP is set at 5.2 percent. To finance this deficit, a sizable amount of public borrowing from the banking sector is projected. Meanwhile, to finance the dramatic rise in private investment, financing from the banking sector would be the key as the underdeveloped capital market is unable to finance private investment. Therefore, there are concerns that with the current problematic condition, the banking sector is not in a position to finance such huge amounts of funds to both the public and private sectors. There is another problem associated with the government's borrowing from the banking sector. The government would have to turn to the central bank to cover the deficit if it did not borrow such a sizable amount from the commercial banks. The Bangladesh Bank will then have to print that money, which will further escalate the inflationary pressure.

Therefore, instead of establishing ambitious goals, this budget needed to concentrate on restoring the macroeconomic fundamentals of the economy.

There are also problems in the allocation for the social sectors. The health and education sectors has been neglected in the past, and the same trends have been maintained this time too. Recovering the learning loss caused by the pandemic remains a big challenge in the education sector. There is hardly anything in the budget as to what steps should be taken to make up for the learning loss. In the case of the health sector, though the allocation was increased during the Covid period, the health ministry could not spend that amount fully. This may be used as an excuse to allocate less funds to this sector. Regrettably, if the efficiency and institutional capacity are not enhanced in the health and education sectors, such a vicious cycle will continue, and the country will never be able to reap the benefits of demographic dividends and achieve large development goals.

How far have the IMF loan conditions been reflected in the budget? There are some reflections, but in most cases, these are not clear. There is a long-standing need for reforms in critical economic domains that have been pending for years. Though the government agreed to carry out reforms under the IMF conditionalities, there are no clear directives in the budget as to how these reforms will be carried out systematically.

Dr Selim Raihan is professor at the Department of Economics of the University of Dhaka, and executive director at the South Asian Network on Economic Modeling (Sanem). He can be reached at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments