Is urbanisation in Bangladesh doomed?

By 2030, half of Bangladesh's population is expected to reside in cities. In a country on track to reach a staggering population of 200 million in seven years, this statistic raises profound concerns about our readiness to embrace the challenges that come with urbanisation.

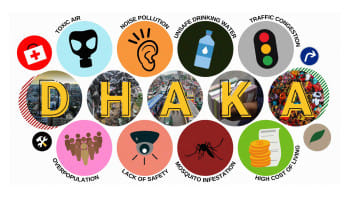

Major cities, including metropolises like Dhaka and Chattogram, consistently rank among the world's least liveable urban areas. They grapple with a multitude of issues. Over 50 percent of the urban population is residing in informal settlements or slums. Citizens also face frequent waterlogging, pollution, traffic congestion, and a severe scarcity of essential services like clean water and health care. These urbanisation-related problems are not limited to major metropolises; they also afflict relatively smaller urban centres such as Bogra, Sylhet, and Barishal. These smaller cities experience unchecked development, significant deficiencies in basic services, inadequate infrastructure, vulnerability to natural and human-made disasters, the gradual loss of green spaces and historic sites, and a host of pollution-related challenges.

The ongoing dengue epidemic, once primarily associated with Dhaka and Chattogram, has now spread across Bangladesh. This underscores how secondary and tertiary urban areas are beginning to replicate the perilous urbanisation patterns of their larger counterparts. The disorganised and unplanned development plaguing our cities has turned them into living nightmares for most residents. On top of all existing challenges, the central government is enforcing a plan to transform our rural centres into urban areas, without any long-term sustainability plan at hand. Given this reality, it is natural to feel anxious about the long-term consequences of such rapid urbanisation.

One can assume that, by 2030, aimless urbanisation will persist, compelling our emerging cities and their inhabitants to adopt unsustainable lifestyles. Inadequate and non-inclusive infrastructure will drive reliance on motorised transportation, forsaking healthier and more economical alternatives like bicycles or walking, resulting in additional health issues. The rapid depletion of natural resources – soil, land, water, vegetation, forests, and open spaces – without regard for regulations will further diminish the overall quality of emerging cities, incurring pollution-related costs. Regardless of their size or significance, our cities may become extensive dumping grounds for all forms of waste, posing significant threats to public health.

So, do our emerging cities possess the capability to intelligently confront the challenges of urbanisation? Or will they unwittingly replicate the mistakes made in the development of Dhaka, Chattogram, and other major cities? While we have glaring examples and lessons illustrating the perils of unchecked urbanisation, the confounding question remains: why are corrective measures not being prioritised? Given that this scenario will directly impact the livelihoods, health, education, and environment of hundreds of millions of people over just the next seven years, the urgency for action cannot be emphasised enough.

We must first acknowledge our institutional shortcomings, from those in the central government to local administrations. Our city and urban planning must transition from the prevailing infrastructure-centric model to one that is more holistic and accounts for the intricate interplay between the economy, environment, and society. Integrated and systematic planning, which views urban space as a complex, interconnected, multi-generational, and multi-scalar system, should take precedence. Inclusive planning, and recognising and valuing diverse cultures and population groups in decision-making, which fosters a greater sense of belongingness, should be practised at all levels. Capacity development and awareness campaigns should prioritise creating safe, inclusive, and sound urban environments for all stakeholders. Instilling an understanding of the value of healthy urban living and its far-reaching positive impacts, especially among decision-makers, is paramount.

Most importantly, local-level policymakers and institutions should be empowered with the capacity for sustainable vision-building and implementation. The case of Rajshahi serves as a living example of how local leadership can catalyse long-term vision-building and its realisation towards a more resilient, liveable future. In the absence of urban leaders to illuminate the path forward, secondary cities, like Rajshahi, must embrace the impending compounded challenges (including climate change) and take the lead in avoiding missteps. Now is the last opportunity for our cities to alter their collective course and embark on a journey towards a brighter, more sustainable urban future.

Dr Nazmul Huq is an urban planner currently working as a sustainability researcher at the University of Applied Sciences in Cologne, Germany. He is also a consultant at the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in its Loss and Damage programme. Reach him at [email protected]

Views in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments