Curriculum and textbooks as weapons

There's a famous Arab folklore on minimalism that goes like this: a group of students visit their elderly teacher years after having left his classroom. The chase for success has brought much stress into their adult lives, and they admit to their teacher that success is not making them happier. The teacher silently leaves to get coffee, which he serves on a tray of various cups—some crystal, some silver, some cheap plastic cups. He asks his students to each take a cup of coffee, and most of them reach for the shiny expensive cups. Their teacher smiles and points out that regardless of the cup, expensive or cheap, the coffee is the same. He explains to his students that if social status is like the cup, life is the coffee. Why try so hard to drink from a fancy cup when all you want is good coffee?

If it were up to me, this is the type of stories I would include in textbooks for children in our primary and secondary schools. I would strive to decolonise the curriculum and content from Western dominance, because it is now more than ever that children need to learn about who they are, where they come from, about our heritage and history. Otherwise, where would our next generations of writers and thinkers come from?

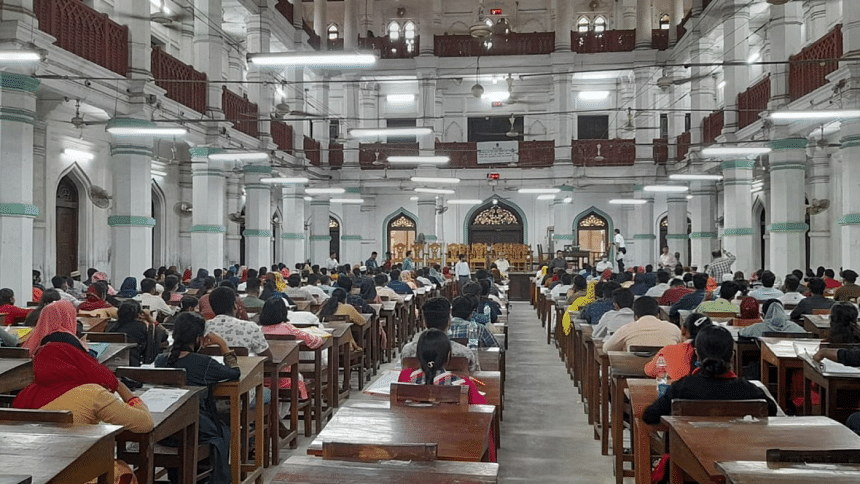

What has won me over about the new recent reforms in the Bangla medium curriculum at school level is that it seems to be shifting the trajectory of educational goals by, for example, including a focus on life skills. But what saddens me is that the process of change remains unchanged. Historically, the Bangla medium curriculum has undergone many experiments, and every time, it's the same lack of transparency that leaves the general public oblivious to how the change came about. Who are these experts that decide our curriculum and choose the content of our textbooks at school and college levels? How do they make the choices they make?

At the end of the day, a curriculum is a weapon; it can be deadly in shaping an entire generation's mindset. It's the trigger that can set off change in the rest of the education system, and it's a good place to start—only if the rest of the components follow suit. If, for example, someone wanted to yield an obedient and disciplined student population, what would be the first thing they would do? Include and filter curriculum content. They would erase stories about revolutions, events where people stood up together against their oppressors. They would make sure there was no content that had a chance of producing free thinkers, because what powerful entity wants its students to have minds of their own?

With the new curriculum taking the Bangladesh social media world by storm, one overarching argument that I see is that students will not be learning "enough" anymore, especially science and maths. But how much is enough? What "knowledge," and how much, does a child carry on from school to higher levels of education in the first place? Does "simplifying" the curriculum really guarantee that children will not be able to pace themselves in higher studies? Did the old curriculum really make the process easier because it "taught" so much? Nobel laureate Esther Duflo calls this the "tyranny of the curriculum"—putting the burden of an immense syllabus on children, which often backfires—ending up with much exam-passing but less true learning.

Does pushing endless information and knowledge on children assure excellence? Are children able to absorb and truly learn what we throw at them? I don't know, really. All I know is that the main goal of a curriculum at the school level should also be to create a thirst for knowledge, curiosity and passion for a subject. It's not meant to give students only a base prerequisite understanding of a particular subject. It's meant to give them insight into a subject to figure out whether they are interested in it or not, so that when they go to college and university, they can make better informed choices in regard to which subject ignites their passion.

I still remember one of the very first things we had been told when starting college: to forget everything we had learnt till then, to unlearn all our learnings. What a waste of energy, we had thought. It was infuriating, and it still is, which is why I am hoping for a good change with the new reforms. These are just my opinions, and I would much prefer a system where I get to conduct research so that my opinions can be backed, or reshaped, by evidence. Those who are opposing the new curriculum, similarly, really don't know whether these changes will bring about more bad than good. Frankly, the government should look to make a team of educationists who are passionate about the nation's education system—a team of varying voices who have actual expertise, knowledge and research on education systems and its components. I want a seat at the table, but for now, here are my thoughts in the boundaries of this column.

Rubaiya Murshed is a PhD researcher at the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge. She is also a lecturer (on study leave) at the Department of Economics, University of Dhaka.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments