An anatomy of interest rates

Interest rate is the price of money and is expressed in percentage: it is the amount a lender charges a borrower. Interest rates are expressed in nominal and real terms, based on the effect of inflation. The nominal interest rate is equal to the real interest rate plus inflation. When a commercial bank borrows from another commercial bank, the interest rate is known as call money rate or call rate. When commercial banks borrow from the Bangladesh Bank (BB) against securities, the interest rate is called policy rate or repo rate. But the rate at which the central bank borrows money from commercial banks is the reverse repo rate. The policy rate is also known as bank rate or discount rate in some countries. In Bangladesh, the bank rate is different from the policy rate and is used for refinancing schemes.

Sometimes banks lend money to their special customers with good credit records at low interest rates, which is called the prime rate. Banks also grant loans like a credit limit for a period where a borrower can use the whole fund during said period. But if they fail to use the same, a special interest rate is charged on the unused portion of the loan. This is called a commitment fee.

Banks determine their lending interest rates based on the cost of borrowing, non-fund operating costs, margin for default risk, and desired profit margin. When they lend to risky borrowers, they determine their lending rates by combining risk-free interest rate and compensation for various risks. The risk-free rate is taken from interest rates on treasury bills and bonds, which are risk-free because the government provides the guarantee for their repayment. And a government does not fail or become insolvent as long as it borrows in its own currency. As bills and bonds are issued in the taka, the government has the last resort on printing money to pay financial obligations.

After setting the risk-free interest rate, a bank considers compensation for different risks it accepts for lending. The first risk is that of default—that the borrower may not repay the loan in full. If the probability of default is high, the rate of return will also be high.

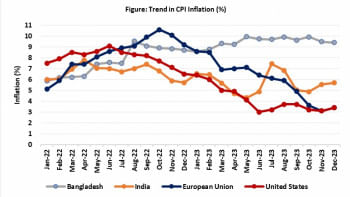

Then comes inflation risk, for which some compensation is estimated. Inflation reduces the banks' real income, that's why, when granting loans, they should consider current and the expected inflation that may rise during the loan term. They must add some premium for this risk.

Next, banks keep some margin to compensate for term or maturity risk, which is associated with the length of time until a loan is repaid in full. When a loan has longer maturity, its risk of non-repayment will be greater. If a borrower has easy access to funds when the repayment of a loan becomes due, the loan is highly liquid. But in absence of such opportunity, the loan may face a serious liquidity risk. A less liquid loan has a greater risk of default. A bank must charge a premium for such a risk as well.

Finally, a bank has to estimate compensation for call risk or prepayment risk of a loan. Call risk is the risk that a loan may be repaid in full before its maturity. A bank with such unexpected inflow of funds faces reinvestment risk. It may have to reinvest the funds at a rate lower than the previous one.

Interest rate risk happens when unexpected fluctuations decline the value of assets. This risk can be related to reinvestment as well as reborrowing. The reinvestment risk arises when returns on funds to be reinvested fall below the cost of funds. The reborrowing risk, also known as refinance risk, happens when the cost of reborrowing funds rises above the returns being earned on investments.

Increase in interest rates has a negative effect on banks' profitability. It may increase interest expense and reduce interest income, generating low profits. Profit reduction is a hindrance to capital accumulation; in order to enhance capital, it is necessary to increase profit continuously. Rise in the interest rate also lowers the value of assets since they have a negative relationship. Increase in the interest rate reduces the amount of capital as well, because any loss in the value of assets is adjusted with capital.

Our banks are already facing the interest rate risk as the caps on the rates have been lifted and they are now determined by the interaction between demand and supply. The latest monetary policy stance, which increased the policy rate by 25 basis points, has further increased the cost of borrowing from the central bank. In such a situation, banks must offer high interest rates to attract deposits. Simultaneously, bank borrowers will have to pay high interests on loans.

A number of banks in Bangladesh have been facing a serious liquidity crisis in the present interest rate regime. Some banks are now offering up to 13 percent interest on deposits. With such a high cost of borrowing, the lending rate must be at least 16 percent to maintain the standard spread—difference between lending and borrowing rates—of three percent. These banks are aggressive because they have acute shortage of funds and want to collect them at any cost. Depositors should not fall in the trap of high deposit rates and they must be cautious about these banks.

When interest rates rise, it increases the cost of a project. Thus, it will be difficult to make the project profitable, increasing the probability of loan default. High interest rates also reduce the number of eligible projects. A project becomes viable only when its rate of return is higher than the cost of borrowing. For instance, when the interest rate (cost of borrowing) is 10 percent, all the projects with a return of more than 10 percent are feasible. If it increases to 12 percent, all the projects with return less than 12 percent are now infeasible. Reducing the number of projects is followed by low economic growth. However, investors only accept projects that have a high probability of success when interest rates rise.

An increase in interest rates attracts foreign portfolio investments—investment in financial assets—provided the interest rate differential between two countries is considerable. This also appreciates local currency, making imports cheaper and exports expensive.

If the interest rate rises, it has multiple impacts on the economy. A rise in interest rates will encourage people to save more, creating more inflow of funds in the banks. In contrast, it makes the cost of borrowing more expensive. People borrow less, which results in less demand for goods and services. When the demand decreases, it also decreases the supply. Then producers produce less, requiring fewer workers. As a result, unemployment rises and people spend less. When people spend less, production falls. The overall result is low economic growth—a paradoxical effect. Still, in order to curb the currently prevailing unbearable inflation, a decline in economic growth may be acceptable for a short period.

Dr Md Main Uddin is professor and former chairman of the Department of Banking and Insurance at the University of Dhaka. He can be reached at [email protected].

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments