Will corporations finally be held accountable?

In what is being considered a watershed moment globally, the European Union approved a law on April 24, marking the 11th anniversary of the Rana Plaza collapse, to hold big brands responsible for human rights and environmental abuses in their supply chains. The proposed EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) requires large companies—defined as those with over 1,000 employees and 450 million euros in net turnover—to conduct due diligence on their environmental and human rights practices throughout their value chains. It empowers regulators to take action against negligent companies and, crucially, offers potential legal recourse for victims of corporate abuses. Rights violations, or "damages caused to a person's protected legal interests" include death, physical or psychological injury, deprivation of personal liberty, loss of human dignity, or damage to a person's property. The law also states that companies have a responsibility to "contribute" to living wages beyond the bare minimum that are now offered as minimum wages in sourcing countries. Corporations can be fined up to five percent of their global turnover for failure to ensure compliance.

Such a legally-binding agreement is no doubt a positive step towards ending highly exploitative practices in the global supply chain. For too long, brands have gotten away with horrible atrocities committed against workers and the environment in their quest for quick profits; in fact, they have consistently refused to take responsibility for creating and sustaining such an exploitative state of affairs by shifting the blame to supplies if and when found guilty of gross violations. The CSDDD—which now needs final approval by ministers of EU member states—promises to end the impunity thus far enjoyed by big corporations.

However, we are disheartened to note that the final draft of the law is a significantly watered-down version than the one originally proposed by rights organisations and unions. The modified CSDDD limits its application to only very large corporations, by raising the thresholds of those covered by the new legislation to 1,000 employees, up from 500, and to those with revenue greater than 450 million euros, up from 150 million euros. It has also excluded certain sectors and extended the time it would take before the directives come into force.

The CSDDD is in many ways a win for rights groups, for it allows trade unions, non-government human rights or environmental organisations to bring civil liability actions on behalf of the aggrieved person. However, such legislation must be adopted by other countries around the world, most notably the United States, and its scope broadened significantly if we are to hold companies accountable in any meaningful way. And while the directive empowers victims with legal options, navigating European courts may prove difficult for many who have suffered abuses. The EU should take effective steps once the law is passed to ensure that the process is truly accessible by workers at the bottom of the supply chain.

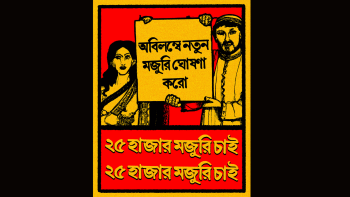

Meanwhile, the new law should serve as a wake-up call for Bangladeshi RMG suppliers—and other exporters at large—for whom the EU remains a most significant export market. It should be apparent to our factory owners that, moving forward, big European companies will no longer take the risk of sourcing from suppliers with questionable labour rights track records. It's high time they realised that protecting human and environmental rights and ensuring transparency within their supply chain are actually in their best interests.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments