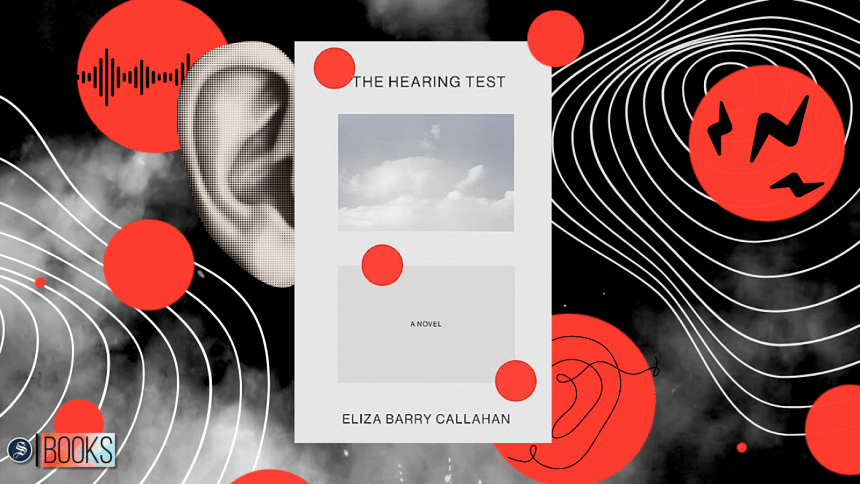

‘Decibels, dollars, days: down’: An experiential novel about hearing and loss

I had a hunch that this author writing about deafness had personal experience of it. I knew because of the consciousness splayed out in the The Hearing Test by Eliza Barry Callahan as she slowly lost her hearing, the detailed accounts of the changing sensations, and the sudden attention to your physical surroundings that doesn't exist prior to the loss of a normal functioning of a body part. It's what happened to me as my muscles tightened the first time I lived alone, and I had vast piles of free time neatly collecting in my room like the bits and pieces you gather to make a new place your home.

It was not just a sudden fall into disability but a sudden loss of able-bodiedness. It might seem like the loss of an ability encapsulates the experience, but in many ways it feels like two worlds have been lived in, particularly when the protagonist seems to have had the privilege of, at least outwardly, a "normal" life.

Callahan's novel came to her during the pandemic when she found herself waking up with a large ringing noise in her head. As she loses her hearing, she seems detached from her surroundings and the people, and even her own gradual loss of hearing. At one point, her mother's friend who is dying tells her over the phone that she preferred to be dead over being deaf.

The protagonist doesn't show strong feelings toward any of this. The distancing language used throughout the book is always something like the "little black dog" and not the dog's name, no matter how many times "little black dog" is mentioned. It has this effect where the author's emotions can't really be gauged. A woman is called a "voice", another a "Miss Baltic Sea", and a former boyfriend who comes in and out of her life is referred to simply as "the filmmaker". Despite this, it is as if the writer is slowly building a world those reading the text can inhabit, almost allowing the reader to embody the experiences not felt personally. It helps that there are incredibly unique descriptions of the hearing problem: "I tried to explain the rolling thunder—It's like god adjusting his piano stool but never getting around to the song".

The text allowed a kind of detached suspension, one which I found calming and much needed as I became restless in my search for a job that wouldn't materialise. At other points, it felt a bit tedious to hear the random tidbits she hears from various people or learns of a belief that they have that is simultaneously mundane-sounding but also perspective-shifting. It is not because these don't advance the plot—this is not the kind of book that one reads for the plot anyway—but because the anecdotes remain small and sometimes unambitious. After a point, it ends up being not enough. Continuing with the text, however, is still rewarding as this first book appears to be from a writer highly talented in using the simplest of language to convey what can seem abstract in the words of someone less skilled.

We see how the protagonist's relationship with even time changes, with her stating, "I was arriving at numbers and leaving numbers behind and meeting them again," and, "Decibels, dollars, days: down"—used as a way to describe her new life.

As if to document the stories that stuck to her in this period of progressive hearing loss that the author was experiencing in her real life, the novel is filled with the most random stories that seem to work in a way you wouldn't expect it to, such as in the case of a story where someone gave birth in the same maternity ward at the same time as Ingrid Bergman, or a classmate in an eighth grade history class who might now be working with the CIA.

The author also ends up peppering the text with various stories involving sound, with one peculiar one including American employees in Cuba being altered by a high-pitched sound, where identical damage was found in each of their inner ears. Some of the stories involve real people and real incidents, veering from Hanne Darboven to Johannes Kepler, from Alan Shepard to Francisco Goya, and Belkis Ayon, a Cuban artist whose art showed people with no mouths but large eyes. She writes about lines, art, and artists—their thoughts and discoveries and their views on things from the planets to daily life—sometimes connected to hearing, sometimes not.

At the part where she describes being at the hospital in LA, I found myself comparing it to my own experience alone at the doctor's. It allowed a way for me to see the writing of my own experiences as a novel. As someone who started maintaining a diary from the age of 11 or 12, first with a cauldron-spilling teenage vigour and then more sporadically as I became older and more erratic, I have been writing for over a decade. I didn't realise it was writing because I was only writing for myself. Hearing that it was an experiential novel, not autofiction or otherwise, made me look differently at what we call the mundane and ordinary and all that slips through to be lost when we mark it as unimportant.

In a way, the novel can almost be a guide on how to novelise your own life. It shows that the mundane need not be tiresome. Journaling at times requires a kind of strength. Often the reserves are empty, or even filled with emotional mines one is not ready to step on. But if you were to mimic writing the way Callahan does, as I found myself doing, the writing may feel easier. Called an experiential document by the author in a podcast, it allowed me to think of past personal events without sinking into the kind of sadness that made movements needlessly heavy. And it helped to remember that there were both fictional and real-flesh-and-blood people going through what I was.

Interweaved with spectacular incidents not one's own, and also filled with the minute happenings of the daily, Callahan's debut is refreshing and recommended for anyone navigating their own period of crisis and feeling unmoored.

Machh is a writer who focuses on otherisations, in both life and fiction.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments