What makes a great university?

What does it take for a university to become a centre of learning, critical thinking, and a space for personal growth for students? Three veteran educationists look into it in the concluding part of a series that focuses on the most fundamental issues of higher education in Bangladesh. The Daily Star welcomes and encourages any and all thoughts, ideas, and recommendations on these issues from our respected readers.

It is universally accepted that great universities must create a "dynamic ecosystem" of enquiry and excellence, offer a "range of sound and relevant academic programmes," hire talented, experienced and dedicated professors to teach eager, competitive and curious students, "embrace change" and emphasise "continuous self-improvement," ensure a "dependable infrastructure" of supporting educational tools and technologies (including modern library resources), maintain a safe, pleasant and comfortable campus, and prepare students for meaningful lives and careers through emphasising their personal agency and autonomy.

All that is true for Bangladesh as well, but unlike other countries, the most serious obstacle to the growth of excellent universities in Bangladesh is the pervasive and profound moral decay within which higher education is located. Administrators stand accused of various financial improprieties, hiring and firing irregularities, political gamesmanship, absenteeism, subservience to student leaders, and so on.

Teachers face allegations of plagiarism, moral turpitude, ugly partisanship, or mercenary pursuits for a little "extra income" elsewhere. Many depend on old and outdated notes and PowerPoint presentations, and most forsake research and scholarships without which good teaching is impossible.

Similarly, students are reportedly guilty of extortion, mugging, "controlling" residential halls, sexual predation, demanding "cuts" from university projects, assaulting teachers, and inflicting a reign of intolerance, if not terror, on campus, where they routinely humiliate fellow students and may even torture them to death.

All this becomes internalised through a conspiracy of silence and impunity. Clearly, no university can flourish in this morbid and moribund environment of corruption, cynicism, and complacency.

Therefore, the first task of a great university in Bangladesh is to tackle this culture and set new standards of conduct, expectation, and moral clarity – boldly and comprehensively. Administrators must demonstrate unimpeachable levels of honesty and accountability, teachers must command respect through their personal qualities and academic abilities, and students must be eager to learn, ready to work hard, and trust the integrity of the scholarly process.

Universities must ensure that the hiring, promotion, and tenure process of teachers is based on norm-based evaluative criteria that are transparent, consistent, and rigorously applied. They must also provide adequate support with resources and incentives particularly for scholarly engagement (to facilitate a vibrant research environment).

Universities must be sensitive to current economic trends and needs so that students are prepared for a rapidly evolving "market." But they must not neglect the social and emotional IQs of the students that distinguish the enlightened from the merely informed. For this, a range of courses in the arts, humanities, history, and the social sciences should be mandatory, opportunities for extracurricular activities must be supported, and elected student governments should be instituted so students could practise democracy, learn tolerance, and respect popular opinion.

Most importantly, great universities must be fiercely and uncompromisingly committed to upholding academic freedom and protecting the right to disagree, particularly in the context of contested narratives and polarised discourses.

Its greatness will depend upon its embrace of "enlightenment" principles based on the laws of reason, evidence, inference and testing in order to advance the "disinterested pursuit of truth," ensure the possibility of questioning all supposedly "established" or "establishment" conclusions and judgements, however widely they may be held or rudely they may be forced (as Popper pointed out, that which is not "falsifiable" cannot be accepted as true), and approach scientific and human progress as a continuing project rather than a finished product or a destination reached.

A mediocre university informs and prepares students for jobs; a good university educates and prepares students for a good life. A great university inspires and prepares students for a rich and fulfilling experience in a changing and challenging world.

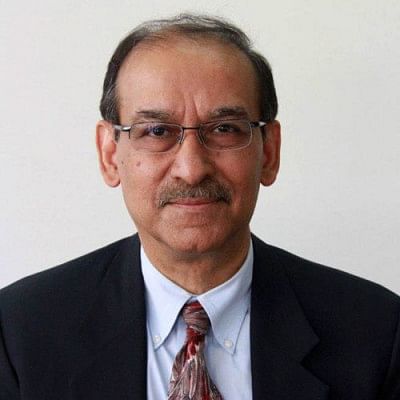

Dr Ahrar Ahmad is professor emeritus at Black Hills State University in the US, and director general of Gyantapas Abdur Razzaq Foundation in Dhaka.

***

Today's academic environment is a disjointed (unconnected parts), disengaged (from reality), and even disregarded (publicly) entity where, among other delusions, faculty members believe they need no training (I wish they would air their reasons publicly), where both administration and faculty members feel there's no use pursuing research (deemed unrewarding but failing unconscionably to recognise its game-changing role), where students decry the value of education as "a waste of time" while situated in a mess of "poor teachers and outdated courses," and where administrative practices have earned public ire for nepotism, financial improprieties, political obsequiousness, coercive practices, poor leadership, and related indiscretions and misdeeds. The vile face of politics in academia needs little elaboration.

The best of universities, globally, shun the above collectively and fervently. Instead, they are "learning organisations" (LOs), structured to promote knowledge generation, learning, and innovation. In a volatile, complex, and changing world, they "must proactively evolve and respond to change swiftly to meet the demand of a knowledge-driven and technology-intensive society."

Peter Senge, a management guru, characterises the LO in terms of five characteristics:

A shared vision where each member contributes to the purpose and goal of the institution, rather than serve as compliant workers.

Mental (shared) models organise the way people act and see things in the organisation. The role of leadership is central here.

Team learning taps into the group mind, vibrant in creative potential, where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

Personal mastery demands clarity in defining personal priorities, seeing reality more clearly, while learning continually.

System thinking binds the other four and embraces the idea of "change management."

The LO facilitates organisational growth as follows (Rick Gibbs):

* It delivers continuous improvement in a culture of innovation and experimentation.

* [Organisational members] are empowered to grow and broaden their skills, boosting engagement and retention rates.

* Today, interdisciplinarity is a marker of high-performing universities. Increased cooperation can help [interdepartmental teams] solve challenging problems using their collective brainpower.

* In a culture of learning, the LO can flourish almost indefinitely.

The top-quality university, capable of navigating uncertain times and adapting to unforeseen circumstances, prioritises knowledge creation, dissemination, and use. This requires a concentration of talent (students, teaching staff, researchers), favourable governance (supportive regulatory framework, autonomy, academic freedom, leadership team, strategic vision, and a culture of excellence), and abundant resources (access to public budgets, endowments, tuition fees, and research grants) (Salmi, 2009).

At the operational level, the best universities foster a challenging academic environment of learning and discovery (research), supported by excellent professors and support staff. They also offer vibrant and up-to-date curricula, avail deep knowledge resources (their libraries and social capital), ensure a friendly, safe and inviting campus, and go the extra mile – providing culture-specific extracurricular activities, affordable transportation, access to healthy food, and decent and accessible living quarters for staff and students. Belonging to such a university fuels pride, camaraderie, a feeling of empowerment, and a ton of confidence to meet life. This is no place that hands out (or even sells) certificates!

Great universities, ethical to the core, are built by the uncompromising 3Ps: people (students of high calibre), people (inspiring teachers) and people (a capable and supportive governance body). But their reach and impact can be limited by the grace, competence, and goodwill of external bodies – the Ministry of Education, University Grants Commission, industry partners, philanthropists, and the public who often fail to see the promise and potential of great universities. When internal and external forces meld into a harmonious whole to achieve the greater goal – build human capacity, transform nation – the sparkle of the great (learning) university can be dazzling and a force to contend with.

Dr Syed Saad Andaleeb is distinguished professor emeritus at Pennsylvania State University in the US, former faculty member of the IBA, Dhaka University, and former vice-chancellor of Brac University.

***

Over the past several weeks, my colleagues and I have been discussing some fundamentally important aspects of a good education system, especially for developing countries like Bangladesh – nations that are trying to overcome their centuries-old backwardness in relation to Western societies and are trying to catch up with a fast-moving world. We've also been hoping to elicit some response from those interested in the issues and from the stakeholders in the system. Our basic premise is that if we want to create a "smart" Bangladesh – as Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has established as a priority – we must, first and foremost, create an excellent education system. Unfortunately for us, the officials who are responsible to facilitate that path have not shown any promise in this regard, and the prospects of achieving that goal seem to be slipping away.

We have discussed what great teachers, students, classrooms, curriculum, and research should look like. Today's topic is what makes a great university. A great university is when all of those aspects mentioned above are established at a superior level. But a great university is much more than that.

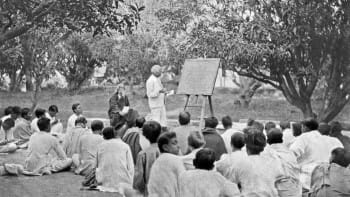

The images of beautiful buildings and happy students walking around campuses like Harvard, Princeton, and Yale appear in our mind as we talk about great universities. But let's put that aside and talk about what a good university should look like, and compare it to what we have.

A good university is a community of scholars, researchers and students coming together to create an environment of learning, critical thinking, and a space for personal growth. What we have at our universities, in general, is quite a bit different: faculty at our educational institutions, for the most part, lack initiative, are uninterested in learning new things, but are quite energetic in securing personal benefits. Researchers are almost an extinct group, and those few that exist often indulge in less-than-high-quality research lacking creativity and originality; not infrequently, they shame their institution by plagiarising other people's scholarship.

Students at these institutions are quite a different beast! Often, groups of politically motivated students turn to violence, create disorder, and resort to other destructive activities. These groups will demand a certificate of a degree without learning much; they'll leave campus without developing much critical thinking or any useful skill for the society. Sometimes, even faculty members align themselves with a political ideology and extort personal benefits. As a result, some of these universities become hotbeds of conservative, fundamentalist, and often extremist political activities leading to violence, disruptions, and not infrequently killings on campuses.

My colleagues have discussed many other requirements of a great university, and I'll refrain from further elaborating on those. However, I want to make a point forcefully: the leader of our nation has given us a beautiful goal - let's create a "smart" Bangladesh! That is a mandate for all the authorities concerned. The bridge to building a smart Bangladesh is to create a superior education system.

But where are we in achieving that goal? It appears that the authorities who are supposed to take up the mandate have failed miserably with a grade far below our national needs or expectations. I believe it's time for those organisations and individuals to take responsibility and become more seriously engaged in this process.

Dr Halimur R Khan is a university professor and can be reached at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments