What’s really causing our non-performing loans to skyrocket?

Non-performing loans (NPLs), or defaulted loans, are an unavoidable consequence of lending, because they arise from varying risks – some controllable, others not so much – related to lenders, borrowers, and the economy. For example, a lender may fail to select a creditworthy borrower, and the borrower may not use the loan productively, leading to a default. Even if a creditworthy borrower is selected, the loan may be defaulted because of poor economic conditions – a systematic risk beyond the control of both parties.

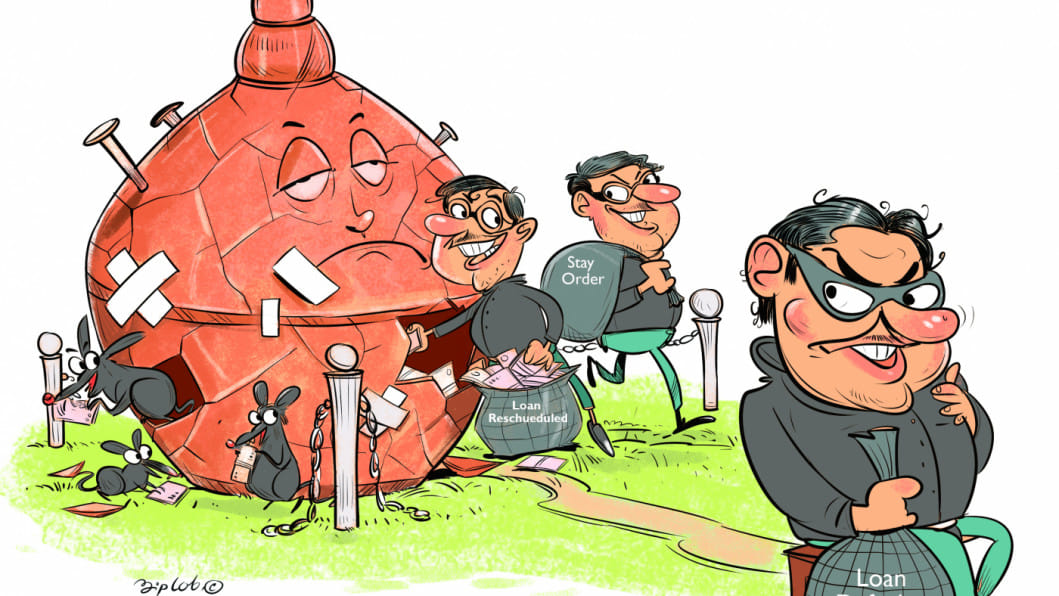

However, the recent rise of NPLs in Bangladesh – to an all-time high of Tk 156,039 crore in June 2023, from the previous highest of Tk 134,396 crore in the third quarter of 2022 – is not due to purely economic reasons. This abnormal rise is not surprising given our banking sector's prevailing nature, and the three fundamental reasons behind this can be identified clearly.

Business-politics nexus

It is alleged that a group of politically-connected people took out large loans from state-owned commercial banks (SOCBs) and intentionally defaulted on them. Later, these swindled funds were used to establish private banks, while the defaulters became their directors. They then started taking loans from the private banks and repeated the strategy of not repaying. Likewise, many unscrupulous businessmen also took loans from banks and defaulted. To avoid legal consequences, a good number of them sought refuge in politics. Political parties also utilised the defaulters, as the former cannot persist without financial support from the latter. And this is how a business-politics nexus took shape in Bangladesh.

In the Banking Companies (Amendment) Act, 2017, the tenure of a private bank's director was increased from six to nine years; the number of directors who could be from the same family was also raised from two to four. The tenure was further extended to 12 years in the Bank Company (Amendment) Act, 2023, while three directors from the same family can now be appointed. Nevertheless, a few banks appointed more than the number of family members allowed as directors.

Many politicians and businessmen have been syphoning money out of banks since the country's independence. Over the years, large loan defaulters emerged from different political parties; they became outstandingly powerful with political patronage and created dangerous situations in the banks. Meanwhile, to institutionalise their position in lawmaking, the businessmen grabbed a good number of seats in parliament.

In national elections between 1973 and 2018, the number of businessmen-turned-lawmakers increased on average. In 2018, around 61 percent of the lawmakers were from this group, up from just 13 percent in 1973 (State, Market and Society in an Emerging Economy, Chapter 10). With such dominance, it is quite unlikely that they would pass any laws that would punish them or their associates.

Due to all this, several banks went through irresponsible lending practices, ignoring rules and regulations. Loans were sanctioned to those politically connected, facilitated by pressure from the banks' boards. The defaulters enjoyed leniency from the authorities, which implies a strong association between business and politics.

Lack of corporate governance

Accountability, transparency, fairness, and responsibility are the basic principles of corporate governance. A firm with good governance has the interests of all stakeholders aligned, and one with bad governance creates doubts about its operations. The many financial scams that occurred in the country, which raised serious concerns among stakeholders, resulted from a lack of governance.

According to central bank rules, a loan can be rescheduled three times after a down payment has been made. In 2015, however, the Bangladesh Bank allowed for a special loan restructuring facility to 11 business groups that were already enjoying the rescheduling facility. The performance of those loans is disappointing. In the Banking Companies (Amendment) Act, 2017, the tenure of a private bank's director was increased from six to nine years; the number of directors who could be from the same family was also raised from two to four. The tenure was further extended to 12 years in the Bank Company (Amendment) Act, 2023, while three directors from the same family can now be appointed. Nevertheless, a few banks appointed more than the number of family members allowed as directors.

In 2018, cash reserve requirements were cut down, allegedly due to the pressure of private bank owners. The government approved state entities to deposit 50 percent of their funds in private commercial banks (PCBs), up from 25 percent. Then in 2019, the defaulters were allowed to remain as regular borrowers just by making two percent repayment of their outstanding loans. These borrowers were also given 10 years, with one-year grace period, to repay their loans. A special policy on loan rescheduling and one-time exit scheme for defaulters was also permitted. The central bank eased the loan classification rule in 2019, deviating from international standards. Loans were also not classified in 2020 and 2021 considering the effect of Covid-19 on borrowers.

While the Bangladesh Bank is responsible for punishing rule violators, it changed the rules in some areas, which worked in favour of defaulters and directors. Family-controlled banks were established by changing the rules, a move that was against public sentiment and expert opinions. Such violations have become common in the banking sector. For example, it was disclosed in parliament that PCB directors took loans worth Tk 171,616 crore (11.21 percent of total outstanding loans) from various banks, exceeding their loan limits. Due to the lack of corporate governance, many banks are now loaded with distressed assets and NPLs.

Legal infrastructure

Adequate legal infrastructure – relevant laws, courts, and impartial judges – are necessary to enforce decisions in a timely manner. A strong legal infrastructure largely supports the credit management of banks.

In Bangladesh, the money loan court was introduced in 2003 for the quick resolution of disputes between banks and clients over loan repayment. There are only seven such courts in the country: four in Dhaka and one each in Chattogram, Khulna, and Mymensingh. Hence, the existing courts are overburdened with cases, which has made the loan recovery process lengthy. According to the central bank, the number of cases reached 72,189 in December 2022; the amount of money stuck in these cases was Tk 166,886 crore.

The money loan courts have been unable to meet the time limits to dispose of the cases; there is undue delay in filing cases, framing charge sheets, and delivering verdicts. Plus, defaulters can always appeal to the higher court, and in most cases, get a stay order in their favour. This lengthy process encourages borrowers to default intentionally and choose to wait it out for years as the courts move at snail's pace. Hence, a strong legal infrastructure is urgently needed to deal with disputed loans.

To expedite disposal of the cases, the law ministry has sent its proposal to the public administration ministry to set up 17 more of such courts: 13 in Dhaka and four in Chattogram. It is expected that the courts will help dispose of the cases once they are established.

But setting up more courts will not bring the desired results if they are not allowed independence in their operations. The authorities must also have the intent to put habitual defaulters on trial and punish them accordingly to establish financial discipline in the banking sector. Thus the courts must be kept free from any kind of interference. Otherwise, from having the second-highest default rate among the South Asian countries, we may rank first soon enough.

Dr Md Main Uddin is professor and former chairman of the Department of Banking and Insurance at the University of Dhaka. He can be reached at [email protected].

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments