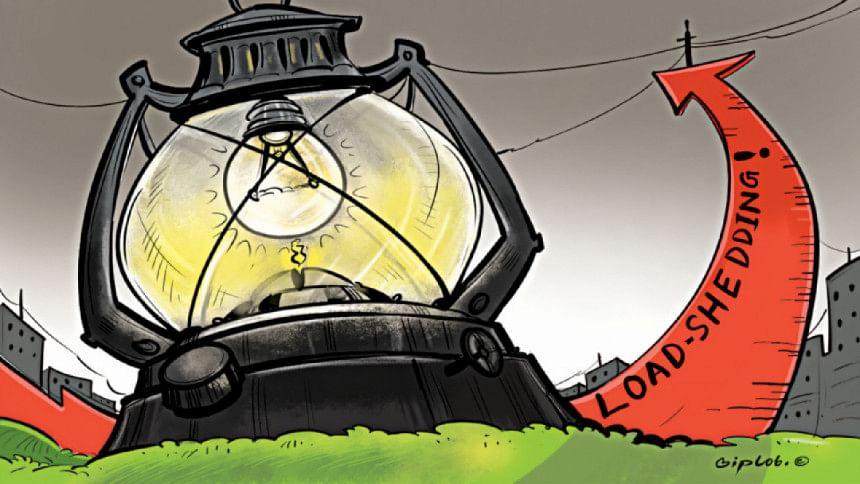

Why do villagers bear the brunt of loadshedding?

The country's people, regardless of where they live, are witnessing an unbearable summer this year. According to the Dhaka Met office, temperatures are an average 2-3 degrees Celsius higher than those of the past decades. Amid this situation, the government is not being able to provide the amount of uninterrupted electricity that people expected to escape from the heat. Those who live in rural areas are suffering the most, as they have no alternative electricity source at home like city dwellers do.

The dollar crisis has hindered the import of coal and gas. As a result, the Bangladesh Power Development Board (BPDB) and Rural Electrification Board (REB) carried out a lot of loadshedding in June and July this year. The REB is mainly responsible for supplying electricity to villages.

According to media reports, the REB had 30 percent less electricity than the demand, causing 8-10 hours of loadshedding in a day, especially in rural areas, during the two months. This has greatly affected everyday life. Although the situation has improved a little, there are still a lot of power outages in the northern districts, especially at night.

Strangely enough, although the government is unable to meet power needs, it pays thousands of crores to government and private power plants as fixed charges or capacity charges every month with taxpayers' money.

On September 5, in response to a question in the parliament, State Minister for Power, Energy and Minerals Resources Nasrul Hamid said during the last 15 years (three terms of the Awami League government), the government paid over Tk 1.04 lakh crore as capacity charges to 82 private and 32 rental power plants.

Interestingly, the government seems to have enforced planned loadshedding in rural areas rather than in urban ones, as large factories, important offices, specialised industrial zones, and, of course, VIPs are situated there. That is why electricity supply has been higher in urban areas. No matter how bad the loadshedding situation may be, none of the helpless people in rural can pressurise power stations to imrpove the situation; they can only wait and hope in silence.

As an alternative source of electricity, most houses, offices, industries, and residential areas in the cities have generators or IPS (instant power supply) devices. But village homes have no choice but to rely on the grid, as the residents cannot afford these alternative facilities.

In the last 20 years, rural areas have developed a lot. But due to the power crisis, residents cannot fully enjoy the benefits of this development. For example, most village homes have refrigerators now. In place of traditional clay stoves, people now use electric rice cookers. And light bulbs have now become ubiquitous. Irrigation systems were also not as dependent on electricity as they are now.

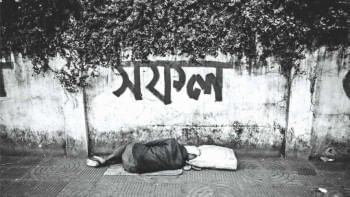

No electricity means disruption of sleep during the hot, humid summer. It means land cannot be irrigated, and students cannot study. When upazila towns don't have electricity, the health complexes cannot perform critical surgeries.

On top of this, people have to deal with absurdly high electricity bills. For example, a farmer whose bill is usually Tk 300 to 400 per month suddenly receives a bill 10 to 20 times the regular amount. If they have three months of dues, their connection is cut off. Many influential people or government offices, however, don't bother paying the bills for years, and nothing happens to them. For example, Social Welfare Minister Nuruzzaman Ahmed, his son, brother, and late father did not pay their electricity bills – amounting to Tk 9 lakh – for the last few years. And yet, Northern Electricity Supply Company (Nesco) did not take any initiative to collect their dues.

However, every month, this very company warns residents of villages and upazila towns using loudspeakers, that those who have bills due for more than two months will have their supply disconnected. This is a clear abuse of power, the likes of which we see too often.

The bottom line is that the electricity boards are entrenched in malpractices and lack accountability, which lead to unbearable sufferings for citizens who pay to get electricity. The policies centring power production and distribution must be changed immediately to relieve people of this misery.

Mostafa Shabuj is the Bogura correspondent for The Daily Star.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments