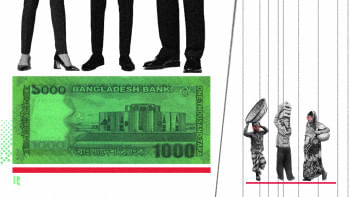

The poor’s debt burden gets heavier

A few days ago, I overheard my part-time household help despairingly comment to her co-worker: "The bazaar prices have caught fire—I can't even buy a single lemon for iftar. I don't know what to eat or cook for my family." At the time, lemons were selling at Tk 10 a piece, with eggplant, cucumber, coriander leaf, and green chillies going for Tk 120 per kg and grass peas at Tk 130 per kg. When I probed her further about this, I found out that every month she has to get basic items like rice, lentils, and onions on credit from her neighbourhood store because her salary was just not enough to pay for food after paying fixed costs for rent and electricity.

If you ask anyone from a low-income group whether they have any loans hanging over their head, there is a high probability that they will say "yes." In fact, they may have taken out a loan from a loan shark at a very high interest to pay off a loan taken from a non-government organisation or a better-off relative. The vicious cycle of taking loans to pay bills and then taking another loan to pay off the first loan may continue throughout their lives, with little or no real improvement in their living standards.

Couldn't a little more effort and political will eliminate the unholy food syndicates, ensure that the list of "vulnerable groups" consists of the really needy and not an upazila chairman's relatives, that the sacks of rice and lentils in aid packages meant for the poor do not disappear into thin air? For once, couldn't those in power take the side of the workers, and not the owners, to make sure they earn a wage that will not leave them hungry and constantly in debt?

One Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics survey from 2023 found that around one-fourth of households in the country need to take out loans for basic essentials—food, shelter, health, and education. Of the over 29,000 households surveyed, each household had taken out a loan of around Tk 49,000 just for food. But the most shocking statistic from this survey is that around 3.77 crore people experienced "moderate to severe food insecurity" last year. Simply put, they have had to skip a meal because they couldn't afford it, or had to frequently stick to a diet that excluded important nutritional items such as fish and meat. The spiralling of prices of practically every essential item has led to there being less food on the table and more desperate borrowing.

Amena, a home worker who has been working since she was 15 to support her family, is all too familiar with this vicious cycle of loans. When she got married a few years ago at age 22, in her village in Kishoreganj, the first shock she got from her husband was that he had already borrowed Tk 1.5 lakh to pay for food and other expenses as his job at a mobile repair shop had not been going too well. So, she began her married life with the burden of a debt, which got bigger and bigger as time went by. Her husband was responsible for supporting his parents and brother, none of whom were earning anything. The only thing to do was to take out another loan to pay the instalments of the first loan in addition to the regular bills. On top of that, Amena's in-laws decided that the couple would have to pay off a loan which their younger son had taken out as he was unemployed. The couple ended up with around Tk 3 lakh in loans and had already started cutting out expensive food items such as chicken or other meats from their diet—opting for eggs or cheap fish instead. Even then, their bill at the local grocery store kept getting longer. Amena began to lose weight and often got sick; but she couldn't afford to go to a doctor. Frustrated and anxious about the loans, Amena decided to go back to work in Dhaka and pay off the instalments. Earning only Tk 10,000 as a household help, she had to send her entire salary to her husband. After about a year, she went back home. Despite all her sacrifices, she and her husband are still in debt, with no savings. With prices of food items soaring to impossible heights, they are faced with the prospect of scrimping more on food items even during the month of fasting.

People like Amena, at least 3.77 crore of them, are undernourished and at risk of ill health because they cannot afford the nutrition they need. In a country that boasts a "tsunami of development" and incredible economic growth, having this large section of the population in such dire circumstances is both unacceptable and immoral. It is unacceptable because of the thousands of crores which have been and are being spent on megaprojects. The Padma Bridge cost Tk 30,193 crore, the MRT Line-6 incurred Tk 33,472 crore, the Dhaka Elevated Expressway cost Tk 13,857.57 crore (including land acquisition and resettlement), and Bangabandhu Tunnel cost Tk 10,374 crore. And it is immoral because only the top 10 percent of the population (a large portion of whom are connected to power) now hold around 41 percent of the nation's total income while the poorest 10 percent claim a mere 1.31 percent.

Putting a price cap on essentials has so far not worked and it is obvious that the government has to intensify its social safety net endeavours to help people pull through these punishing inflationary pressures. How much would the government have to spend to make sure that the majority of the population does not go hungry or suffer from undernutrition? Wouldn't a fraction of these monumental megaproject cost figures help boost the existing social safety net programmes, substantially increase the number of OMS trucks selling subsidised food, give extra support to farmers and bring back free meals in schools? Couldn't a little more effort and political will eliminate the unholy food syndicates, ensure that the list of "vulnerable groups" consists of the really needy and not an upazila chairman's relatives, that the sacks of rice and lentils in aid packages meant for the poor do not disappear into thin air? For once, couldn't those in power take the side of the workers, and not the owners, to make sure they earn a wage that will not leave them hungry and constantly in debt?

Sharing even a miniscule percentage of the top 10-percent's wealth with their less fortunate compatriots could make growth more inclusive in this country and give authenticity to the development narrative.

Aasha Mehreen Amin is joint editor at The Daily Star.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments